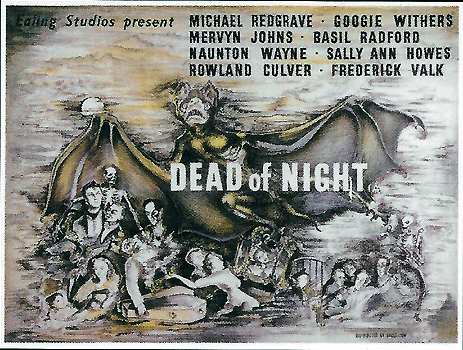

Dead of Night (1945) ***½

Dead of Night (1945) ***½

The 60’s and early 70’s were the heyday of the horror anthology movie, but the first classic of the form appeared considerably earlier, during a curious period in the history of the British fright film. Critical opinion and censorship policy were no less hostile to the genre in the second half of the 1940’s than they had been before or would become later. Nevertheless, the immediate postwar years were characterized by a defiant boomlet in the UK cinema of the macabre— this at the very same time that Hollywood’s horror output was slowing to a pathetic trickle. Most of the films from this strange mini-efflorescence are largely forgotten today, and somewhat difficult to see. Dead of Night, however— the only horror movie from the highly regarded Ealing Studio— retains a bit of reputation, even if it’s little more readily accessible than the likes of The Rocking Horse Winner or The Queen of Spades. That’s because Dead of Night has yet a further claim to distinction in addition to its timing and its inspirational effect upon subsequent anthology scare flicks. So far as I can tell, Dead of Night seems to have marked the debut of the “evil ventriloquist’s dummy” trope in its mature form.

Let’s not get ahead of ourselves, though; the dummy doesn’t show up until segment five. We should begin at the beginning, with architect Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns, of 1984 and The Old Dark House) pulling up the long driveway to a new client’s country estate. As Craig soon explains to his host, Eliot Foley (Roland Culver, from The Legend of Hell House and The Uncanny), seeing the place for the first time gave him a start, for the rather eerie reason that it wasn’t the first time. Craig has visited Foley’s house any number of times in a recurring nightmare that he can never quite remember by the light of day. Nor is it just the house that figures in Craig’s dream. Foley is in it, too, along with his mother (Mary Merrall) and every one of the four other guests the pair are currently entertaining. There should be a sixth guest as well, although Craig doesn’t see her in Foley’s drawing room— a dark-haired woman in need of money. Naturally Foley and all his guests find this very interesting. Even Dr. Van Straaten (Latin Quarter’s Frederick Valk), a psychiatrist by trade, feels compelled to speculate on the cause of the phenomenon, although he rejects out of hand the kinds of paranormal explanation that leap into the minds of his fellows. The conversation quickly turns to the other guests’ brushes with the inexplicable, establishing both the frame and the pattern for the rest of the film. One by one, the guests tell their stories, Van Straaten attempts to explain them away, and seemingly innocuous occurrences between tellings lead the increasingly agitated Craig to recall further details of his recurrent nightmare— and eventually to fear that whatever beclouded horror concludes it is about to enfold him in real life.

Hugh Grainger (Anthony Baird, from The Clue of the Twisted Candle and The Ghost of Rashmon Hall) is the first to speak, even before the full strangeness of Craig’s position is apparent. He too had a prophetic dream once, during the hospital stay that introduced him to his wife, Joyce (The Black Abbot’s Judy Kelly). She was a nurse, you see, while he races cars for a living— a profession that sees just about all of its practitioners under in-patient medical care sooner or later. Grainger’s crash was a bad one. The other driver was killed, while he received a concussion, several broken bones, and extensive severe burns. Hugh was delirious all through the first several days of his convalescence, but his weird experience happened only after he regained his senses. He got up out of his bed in what he believed were the wee hours of the morning, and went to look out the window. The scene out there was not what it should have been, and there was an old-fashioned horse-drawn hearse standing in the road just outside. Its driver (Miles Malleson, from First Men in the Moon and Peeping Tom) looked up at him and called out, “Room for just one inside sir,” which gave Hugh quite the wiggins, even if it was the simple, factual truth. When Grainger returned to his bed, he discovered that it was a mere five minutes since he had lain down in the first place, which hardly seemed long enough for him to fall deeply enough asleep to dream. But the truly uncanny part came later, on the day of Hugh’s release. He intended to take a bus home from the hospital, but when he went to board it, he recognized the driver as the man with the hearse from his dream. And would you believe the driver said to him as he started to board, “Room for just one inside, sir?” Grainger decided on the spot that he was not going to be that one, and a good thing, too. The bus didn’t make it past the first corner before it was run off the road by a reckless driver, and everyone aboard was killed in the crash. No sooner does Hugh finish telling this tale than his wife— his brunette wife— arrives at the Foley house, and asks him if he would mind paying the cab driver for her. Seems she spent her last few shillings on the train from London.

Sally O’Hara (Sally Ann Howes, from Death Ship and another of the many versions of The Hound of the Baskervilles), the youngest of Foley’s guests, goes next. Her story concerns a Christmas party she attended some years ago at the palatial home of a family friend. There were about a million kids in attendance, and at one point they all decided to play a variant of hide-and-seek which they called “Sardines.” The idea is that instead of one person hunting for a mass of hidden players, just one player hides at first, and each seeker who finds them must then squeeze into the same hiding place until everyone has caught on. Sally was initially discovered by a boy named Jimmy Watson (Michael Allan), who annoyingly had the hots for her. She managed to dislodge him when he suggested that they cheat by finding a better hiding place, but not before he told her that the mansion was reputedly haunted. Evidently it was once home to a pair of siblings, the older of whom killed first her brother and then herself; no one is entirely sure which child is supposed to be the ghost. After ditching Jimmy, Sally retreated far into the mansion’s labyrinthine uppermost floor, where she encountered a young boy she didn’t remember seeing earlier. The kid was crying over something to do with his sister (whom Sally couldn’t recall meeting, either), but settled down and went to sleep after Sally spent some time with him. When she returned to the party a short while later, she learned that the strange boy could not be accounted for among the invited guests, and that the name by which he called himself was also that of the legendary juvenile murder victim. And with her story told, Sally is hustled off to her uncle’s birthday party by her newly arrived mother (Barbara Leake, of A Study in Terror), just as always happens in Craig’s dream.

Joan Cortland (Googie Withers) has Hugh and Sally both beat by a country mile. She once accidentally bought her husband, Peter (Children of the Damned’s Ralph Michael), a curse for his birthday. Peter is fond of antiques, you see, and the year before they were married, Joan found the most gorgeous old triptych mirror at a price she couldn’t refuse. But as soon as he hung her gift up in his bedroom, it became clear that there was something peculiar about either it or him. Although Joan herself never saw anything out of the ordinary when she looked into the glass, Peter swore that it reflected a different room from the one it actually occupied. The reflected room was much larger and more grandly appointed, fit perhaps for some lord or lady of the previous century. Peter and Joan alike assumed at first that he was having hallucinations brought on by overwork, but then his personality started to change. That spooked Joan badly enough to make her return to the shop where she bought the mirror, so as to ask the proprietor (The Frog’s Esme Percy) for any information he might have regarding its background. It was one hell of a story she got. Evidently the mirror was witness, so to speak, to a gruesome murder-suicide. The original owner strangled his wife in a rage over her imagined adultery, then cut his own throat. And wouldn’t you know it, paranoid jealousy about Joan’s relationship with a male friend was the most prominent element of Peter’s shift in demeanor. Joan had to destroy the mirror to prevent the Cortlands from sharing that long-dead couple’s fate.

Craig is growing visibly distressed at this point, so Foley attempts to lighten the mood. He tells of something that happened to two friends of his from the golf club— although I rather think he’s having Craig on, since there’s really no way he could have learned most of the story even if it were true. George Parratt (Basil Radford) and Larry Potter (Naunton Wayne) were the best and most loyal of friends, but they were arch-rivals on the links. Indeed, their sporting enmity was so great that all their acquaintances marveled that it didn’t infect the rest of their friendship. But George and Larry’s bond survived what ought to have been an even more serious challenge when they each fell in love with the same woman, and Mary Lee (Peggy Bryan) found herself unable to chose between them. The triangle persisted unresolved until one day George proposed to settle one rivalry by means of the other. The men would wager Mary’s love on eighteen holes, with the loser going away forever and leaving the winner to woo her unopposed. As it happened, though, Larry took a rather drastic interpretation of “going away forever” when he emerged from the contest just a single stroke short. In a golfer’s version of seppuku, he strode off at once to drown himself in the nearest water hazard. Obviously that was meant to be the end of the affair, but Larry learned something shocking upon arriving in the afterlife, where all Earthly secrets are unveiled: George, that son of a hamster, cheated! Plainly there was nothing else for it but to return from the grave and haunt the rotter until he came clean…

Speaking of coming clean, the accumulating weight of testimony compels Dr. Van Straaten at last to admit that even he has had what some would no doubt consider a paranormal experience, although he himself maintains that it was entirely explicable within the ambit of human psychology. In any event, Van Straaten was once called in as an expert witness for the defense of a man accused of attempted murder. Oddly enough, both perpetrator and victim were professional ventriloquists. According to the statement of the latter, one Sylvester Kee (Hartley Power), he and the defendant, Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave, from The Innocents), met at the Chez Beulah nightclub in Paris, on a night when Frere was performing. Frere’s was mostly the usual shtick, with him acting the straight man to Otto the dummy, who was basically an insult comic. Perhaps the vein wasn’t so totally played out in the late 1930’s, when this presumably happened. Frere drew Kee into his act like any other paying customer, but with him the routine was a little different. Instead of creatively berating the other ventriloquist, Frere had Otto talk like he was interested in going into partnership with him in Maxwell’s place; Frere feigned increasing irritation as the dummy proposed terms for dumping him from his own act. Kee formed the impression, though, that Frere really did want to discuss some manner of collaboration, especially at the end of the show, when Otto leaned out through the curtains one last time to reiterate an invitation up to Maxwell’s dressing room. That was the beginning of an insane running charade in which every time Kee and Frere met, the latter would propose partnership in the dummy’s persona while angrily refusing it in his own, culminating one fateful night in London, when Frere shot Kee in a paranoid fury over the schemes he and Otto were supposedly hatching behind Maxwell’s back. Van Straaten chalked it up to multiple personalities, of course, but Kee never could shake the feeling he started to get toward the end that Otto might really have been acting without input from his owner. Having finished his tale, Van Straaten fumbles and breaks his glasses, causing the last pieces of Craig’s nightmare to fall into place in his memory. The psychiatrist is about to wish they hadn’t.

The most conspicuously unusual thing about Dead of Night is that its framing story truly is a story, with its own characters, conflict, rising action, climax, and resolution. The other five segments are separate from that story as you’d expect, but they’re also relevant to it and even help to move it along. Later anthology movies have often aspired to such integration, but more often than not wound up with frames that were mere vehicles for cheesy and predictable twist endings. The only ones I’ve seen to equal Dead of Night for the substance of the framing story are From Beyond the Grave and Asylum— and the latter cheats a bit by channeling the frame into the final segment, ultimately erasing the distinction between them. On a related note, Dead of Night is also one of the few films I’ve seen in which “it was all just a dream” serves to exacerbate the horror rather than copping out from it. Indeed, given how early the subject of Craig’s recurring nightmare is raised, that normally contemptible trope gives this movie an air of dreadful inevitability.

The stories within the story are the typical varied lot. Hugh Grainger’s bus to Hell and Sally O’Hara’s haunted Christmas party are slight and unmemorable (even despite the former’s basis in E.F. Benson’s oft-adapted “The Bus Conductor”), but that’s forgivable in context. After all, they’re the first two tales, and it wouldn’t do for Dead of Night to leave itself no room for escalation. That escalation comes first in the form of Joan Cortland’s cursed mirror, then again and most forcefully with Van Straaten and the ventriloquists. Those two stories have the sharpest claws I’ve seen bared by any British horror movie of the pre-Quatermass era, along with a psychological maturity that’s rare in fright films of any age or nationality. The mirror segment is like something out of M.R. James, with its mindlessly malign inanimate object whose evil power is rooted in a crime of centuries past. But in stark contrast to James, its sensibilities are thoroughly modern, its protagonists urban sophisticates whose first approach to explaining and combating the haunting is rooted in the science of the mind rather than the mystic lore of antiquaries. It’s worth remarking on Joan’s hard-headed practicality, too, even if Britain’s screenwriters of the 1940’s weren’t quite so reflexively dismissive of feminine capabilities as their counterparts in Hollywood. As for the puppet segment, its greatest strength is that it leaves the matter of Otto’s sentience genuinely unresolved, and is equally disturbing either way. Bonus points, too, for slipping so much ribaldry into Frere’s stage act. The jokes seem tired and tame now, but this was pretty edgy stuff for 1945. My favorite line comes during a bit in which Frere and Otto are ostensibly trying to sort out whether they’ve seen a particular buxom blonde before. Frere asks if perhaps they might remember her face from the Folies Bergere in Paris, to which Otto retorts, “Why would I be looking at faces at the Folies Bergere?”

In between those two highlights comes Eliot Foley’s story of intrigue on the golf course and its supernatural consequences, and I frankly don’t know what to make of that one. Normally, an unfunny comic interlude would earn nothing but scorn from me, but this one has a few muted virtues. Most importantly, although the execution isn’t funny, the premise is. Folding together comedy of manners, comedy of errors, a subversively mocking attitude toward the leisure class, and a hefty dollop of sheer absurdity, it would have made a superb Mitchell and Webb sketch. Larry Potter’s is the most polite and apologetic revenge from beyond the grave that you’ll ever see, and yet simultaneously a terrible one indeed when you start to consider all the practicalities. And the note on which the story ends is so kinky that I can’t understand how it evaded the censors at all. I get why Dead of Night’s first American distributors trimmed the golf-and-ghost segment (along with the boring Christmas party yarn), but I would have felt a bit cheated had the version I watched not included it.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable on horror anthologies. Click the banner below to read my colleagues’ contributions:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact