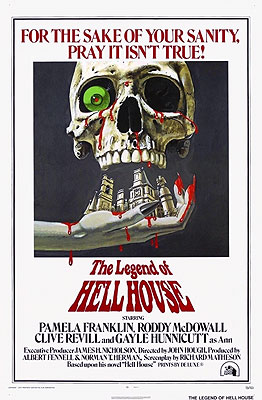

The Legend of Hell House (1973) ***½

The Legend of Hell House (1973) ***½

The conventional explanation has it that The Exorcist paved the way for the demise of the British horror film by driving up the budgets for top-flight movies in the genre to a level that the smaller U.K. cinema industry simply couldn’t afford. This seems as good an explanation as any to me; at the very least, it has to be more than coincidence that the big British horror studios— Hammer, Amicus, and Tigon— all went bust or abandoned the genre in which they’d made their names during the mid-to-late 70’s. So it seems awfully fitting that 1973— the year of The Exorcist— was also the year of The Legend of Hell House, one of the last great English horror flicks. Though it is marred by an overwrought performance from an increasingly out-of-control Roddy McDowall and an ending that depressingly prefigures the horrendous 1999 remake of The Haunting, this remains one of all-time heavy hitters in the haunted house subgenre, surpassed only by the original The Haunting and Kubrick’s The Shining.

That should come as no surprise after you’ve watched the opening credits. The Legend of Hell House was based on Hell House, one of Richard Matheson’s very best novels, and Matheson himself was called in to write the screenplay. Dr. Lionel Barrett (Clive Revill, who got a lot of work as a cartoon voice-actor in the mid-80’s; his credits include “Snorks,” “Dragon’s Lair,” and “The Transformers,” on which he was the voice of the Insecticon Kickback) is a physicist-turned-parapsychologist who believes that there is a perfectly rational explanation for the phenomenon popularly known as the haunting. One day, he is offered the job of finding the final answer to the question of survival after death by an ancient, eccentric multimillionaire named Rudolph Deutsch (Roland Culver, from The Uncanny and Dead of Night). Deutsch will pay Barrett £100,000 for his services; an equal sum will go to each of the mediums with whom the old man wants Barrett to work. At first, Barrett balks at the idea— Deutsch is allowing him only a single week to answer a question that all of humanity has wrestled with for millennia— but he changes his tune when Deutsch tells him where he’s going to be conducting his research. The Belasco house, far out in the English countryside, is considered by parapsychologists to be “the Mount Everest of haunted houses.” The phenomena manifested there are the stuff of legends, but the place has not been investigated since 1953, when a team of researchers met with horrible fates while trying to unlock its secrets. The house was sealed up, and no one has been allowed to go near it for 20 years. But now the owners of the old mansion have fallen on hard financial times, enabling Deutsch to talk them into selling the place to him. Deutsch wants Barrett to begin the investigation the following Monday.

With both £100,000 and a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to further his research dangled before his face, Barrett signs on. He and his wife, Ann (Gayle Hunnicutt, from Voices), drive out to the mansion, where they meet up with Barrett’s new partners. Florence Tanner (Pamela Franklin, of And Soon the Darkness and Food of the Gods), apart from her age, is more or less what most people envision when they think of a medium. She’s a pretty, young woman (a bit flighty, though) who believes she has been endowed by God with a rare ability to communicate with the spirits of the dead in order to help them find peace in the afterlife. Ben Fischer (Roddy McDowall, from Planet of the Apes and It!) is what parapsychologists call a physical medium. He doesn’t talk to ghosts, but rather enables them to interact with the physical world by tapping his own psychic/psionic powers. Fischer also has a history with the Belasco house. When he was fifteen years old, he was part of the ill-fated 1953 research team. He was also the only one of them to come out of the house alive, sane, and uncrippled.

Fischer proves to be a valuable source of information about Hell House and its history as well. The place was built in 1919 by Emeric Belasco (also known by the nickname, “the Roaring Giant”), a decadent plutocrat with a reputation for moral loathsomeness. His mansion was the scene of innumerable orgies both sexual and pharmacological, and enough madness, murder, and suicide to spawn a hundred hauntings. (Attentive viewers who have also read Matheson’s book will note that the movie decorously omits the especially nasty detail of the “Bastard Bog,” where Belasco’s female guests would drown the unwanted issue of their promiscuous couplings under Hell House’s roof.) Belasco himself rarely partook of the debaucheries directly, but seemed content to get his kicks vicariously by watching and encouraging the bad behavior of his guests. Eventually, the party ended in a mass murder/suicide, but oddly enough, Emeric Belasco was not found among the victims. But as he was not found alive anywhere, either, it seems pretty likely that he died along with his compatriots. The fact that the haunting set in right about then would also seem to point toward Belasco’s demise.

The supernatural nastiness begins almost immediately. During her first sitting, Florence Tanner channels what she believes is the spirit of Belasco’s son. Speaking through her, the younger Belasco threatens to kill all of them if they do not leave at once. And strangely enough, though Florence Tanner has always been a mental medium, under the influence of Hell House, she begins exhibiting such traits of the physical medium as telekinesis and the production of ectoplasm. It rapidly becomes evident that whatever lurks in the Belasco house wants to isolate the researchers and pick them off one by one. Barrett’s instinctive distrust of Tanner’s technique and his disbelief in her explanation of the haunting (Barrett doesn’t even believe in ghosts or spirits, at least not in the sense that most people use the terms) gives the house a handy wedge with which to accomplish this, and it never lets slip an opportunity to exploit the two researchers’ rivalry. Meanwhile, the evil of Hell House begins possessing Ann, seeking to use her to restart the sexual perversity with which the old mansion is so accustomed to being filled. (Not only that, it takes matters into its own hands, as it were, by subjecting Tanner to direct spectral rape!) And because it turns out that none of the characters has figured out the whole truth behind the haunting of the Belasco house, there’s a pretty good chance that the investigation of 1973 will end much the same way as its predecessor did 20 years before.

Like most haunted house movies, The Legend of Hell House plays as much like a series of self-contained set-pieces as it does like a continuous narrative. Indeed, it bears a particularly strong resemblance in this respect to the earlier The Haunting, though Hell House is far more aggressive in its dealings with the investigators than Hill House, and the scare scenes in this movie carry more visceral charge. This ought not to be terribly surprising, though, because the novel Hell House also reads very much like a pulp version of Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House, and with the same man writing both the print and film versions of this story, one would expect the latter to be a fairly faithful adaptation of the former. Indeed, it is this very fact that makes this movie’s climax such a puzzle. For who knows what reason, Matheson has rewritten the final confrontation between Fischer and the evil force that haunts the Belasco house in such a way that what was originally a clue to the haunting becomes the entire explanation for it. A detail that, in the novel, offers an insight into the character of Emeric Belasco has expanded here until it becomes the key to his entire personality, and thus the root cause of everything that has happened inside Hell House over the years. The unfortunate effect is to cheapen Belasco and his unholy house considerably, reducing nearly cosmic evil and an almost superhuman villain to the level of a garden-variety inferiority complex. The rest of the movie is so good that it remains a forgotten classic even in spite of this grave miscalculation, but the ending is still a terrible disappointment, still more so now that it has been reproduced in an even cruder, even sillier form in Jan De Bont’s execrable revision of The Haunting. Had it not been for the baleful effects of the final ten minutes, it probably wouldn’t be necessary today to qualify the classic status of The Legend of Hell House with the adjective “forgotten.”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact