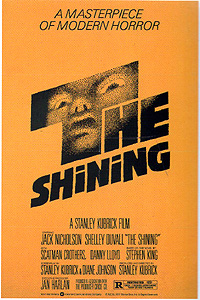

The Shining (1980) *****

The Shining (1980) *****

Reverence is not a tone I’m accustomed to taking in these reviews, even— indeed, perhaps especially— in the case of films to which reverence is generally accorded. But no lesser reaction seems merited in the face of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. As far as I’m concerned, this is quite simply the finest horror movie of all time. Yes, yes— I know. Stephen King has gone on record any number of times expressing his dismay at how the movie turned out, saying that Kubrick missed pretty much the entire point of his novel. And as the author of the movie’s source material, that’s King’s prerogative. But since I’ve always thought of King’s The Shining as a cliché-ridden and mostly pedestrian haunted house tale, missing the point seems more likely to improve a film adaptation than to detract from it. You see, Kubrick’s version achieves something that none of King’s writing ever has— it scares me. Not only that, hardly any of the things in the movie that scare me even appear in the book, in any form. And while it may disregard the point of the novel, the movie has a point of its own which I find much, much creepier.

I’m sure you all know the story by now, but regardless… Jack Torrence (Jack Nicholson in what, for better or for worse, would become a career-defining performance) is an unsuccessfully aspiring writer who has just recently quit his teaching job. Looking for a long stretch of solitude to help him focus on his current book, he has decided to take a position as the winter caretaker at the Overlook hotel, a huge and luxurious resort in one of the most remote sections of the Colorado Rockies. Jack loves the place, and he is actively enthused at the notion of being cut off from virtually all human contact for the five months when the heavy winter snows make the hotel all but impossible to reach. Jack’s new boss, Stuart Ullman (Barry Wilson, of Island Claws), is happy to hear that, especially in light of the ugly incident that happened at the Overlook over the winter ten years before. In October of 1970, Ullman’s predecessor hired a man named Grady (and if you pay close attention, you’ll catch Kubrick and company in a really stupid slip-up: Grady’s first name is given as “Charles” when Ullman tells the story, but later on when he begins to assume a more important place in the narrative, he is identified as “Delbert” instead) to do the job that Jack is about to take on. Grady turned out to be bothered a great deal by the seclusion inherent in his role, and one day he went absolutely nuts. So nuts, in fact, that he chopped his wife and twin daughters to pieces with an axe. The unflappable Jack Torrence merely tells Ullman that he needn’t worry about anything like that happening on his watch. Famous last words, as they say…

At the other end of Colorado, the other two members of the Torrence family are discussing Jack’s new job. His wife, Wendy (Shelley Duvall, from Time Bandits and Tale of the Mummy) seems to be guardedly optimistic about the idea of spending five months holed up in a hyper-luxury resort hotel, but Danny (Danny Lloyd), the Torrences’ six-year-old son, is none too pleased with the situation. Neither, for that matter, is Danny’s imaginary friend Tony— the “little boy who lives in [Danny’s] mouth.” The funny thing about Tony is that he seems awfully real for an imaginary friend. It isn’t just that Danny holds what sound like real conversations with Tony (Danny affects a somehow disconcerting gravelly squeak for Tony’s voice, and wiggles the index finger of his right hand in time with the imaginary boy’s words), but rather that Tony— unbeknownst to Danny’s parents— seems to know things that Danny doesn’t. How can that be if Tony’s just a figment of the boy’s imagination? In any case, Tony has his reasons for wanting to stay away from the Overlook, and, after much prodding from Danny, is finally persuaded to clue the latter boy in to the nature of those reasons. Danny lapses into a sort of trance, and what Tony shows him while he’s under is so alarming that he goes into shock and passes right out in the middle of brushing his teeth. The doctor Wendy calls can find nothing physically wrong with him, and reassures her that it’s probably nothing serious.

A few days later, the whole Torrence family is on the road to what will be their new home for the next five months. Ullman meets them in the lobby and takes them on a tour of the hotel, which, as you might expect of a playground for the very rich, is outright intimidating in its vastness. As the tour nears its conclusion, Ullman sends Wendy and Danny off to have a look at the kitchen in the company of the Overlook’s head chef, Dick Hallorann (Scatman Crothers, from Truck Turner and Slaughter’s Big Rip-Off). You wouldn’t think there’d be much potential for eerie goings-on in a hotel kitchen, but that’s only because you haven’t met Dick Hallorann yet. First he starts calling Danny by the same nickname as his parents do— Doc— without being told about it or even hearing one of them use it. Then, while he’s talking to Wendy about the contents of the enormous walk-in pantry, Dick shoots Danny a look and the boy hears the words, “How about some ice cream, Doc?” resounding inside his head. Seems Danny’s not the only one with paranormal powers around here.

Dick arranges to get Danny away from his parents for a bit so that he can talk to the kid about their shared gift— what Grandma Hallorann used to call “the shining.” It isn’t just a desire to bond with another person possessed of this rare talent that motivates the old cook, however. You see, in addition to being able to communicate telepathically and catch vague, dreamlike glimpses of future events, people who shine can see a few other things that normal folks can’t. The way Dick explains it, some events can leave traces of themselves behind— “like when someone burns toast,” except that the traces Dick is talking about can be detected only by people who have the shining. This is an important point for a young psychic boy to remember while staying at the Overlook, because “a whole lot of things have happened in this here hotel over the years, and not all of them was good.” Now these ghosts, for lack of a better word, are basically harmless, having no independent existence in the real world, but they seem completely real, and a person who doesn’t know better could perhaps be made to hurt themselves in panic over them. There’s just one thing about Hallorann’s spiel that doesn’t add up right. If the ghosts of the Overlook are harmless, then why is Dick (despite his denials) so obviously afraid of room 237?

As it turns out, whatever waits in room 237 is the least of anyone’s worries. It may have slipped by Dick’s heightened senses, but Jack and Wendy have just the slightest bit of shine to them, too— Jack apparently more so than his wife. That means they can also pick up the signals the Overlook is sending, but with no one to help them make sense of it all, they are vulnerable to the worst of the hotel’s possible effects. Vulnerable, in case you hadn’t guessed this, the same way Grady was vulnerable back in 1970. Indeed, it seems Hallorann may have underestimated the Overlook; judging by the concerted way in which its apparitions (including Delbert Grady [Philip Stone, from Unearthly Stranger and A Clockwork Orange] himself) attack Jack Torrence’s sanity, I’d say it’s become much more than just a library of unsettling psychic movie clips. It might not be overstating the case to say that the Overlook has achieved its own form of malevolent life.

Back in the first paragraph, I said The Shining was scary. Now let me try to give you some idea of how scary. A couple of years ago, I dated a girl whose idea of a horror movie had been The Craft before she met me. Such a thing would never do, of course, so I took it upon myself to introduce her to the real deal, in the form of Night of the Living Dead and The Shining. The Romero movie (black and white, cheaply made, often unconvincingly acted despite its seemingly obvious greatness in other departments) had little effect on her, but The Shining was another matter altogether. For the whole of the final reel, from the disastrous failure of Dick Hallorann’s rescue attempt to the concluding zoom-in on the 80-year-old photo that has inexplicably changed in an eerily impossible manner, this movie reduced my date to little more than 100 pounds of quivering, whimpering protoplasm. At the other end of the experience spectrum, I— hardened as I am to such things— get chills up my spine just thinking about the two little girls Danny starts seeing wandering the Overlook’s corridors after a few weeks of living in the hotel, or the revelation of what’s in room 237, or the scene in which Wendy discovers that Danny has retreated completely within his mind, and that only Tony remains. (“Danny isn’t here now, Mrs. Torrence.” Damn, that creeps me out!) I can’t think of even one other horror film that has such a profound and consistent effect on me as this one.

Turning our attention to the question of why that should be, let’s start at the top. I dearly wish writer/director Stanley Kubrick had made more horror movies, because his style is perfectly suited to them. His notoriously meticulous control over every aspect of production enables him to invest an entire two-hour-plus film with a feeling of nightmarish disorientation the likes of which most directors in the field count themselves lucky to achieve in just a handful of scenes. Kubrick also clearly spends far more time thinking about what the camera will allow him to do than most other directors, and The Shining is filled with strikingly composed shots filmed from all sorts of odd angles and perspectives. Such things as the aerial shot of Wendy and Danny exploring the immense hedge maze on the hotel grounds or Jack’s half of the conversation he has with his wife after she locks him in the pantry (which is shot from a position on the floor between the man’s legs) will naturally get the most attention, but even more effective are such simple, subtle tricks as filming all the scenes that focus on Danny through a distance-magnifying lens at a six-year-old’s eye level. Kubrick also knows well how to make use of pacing to enhance the effect of a story. The Shining is filled with strange accelerations and decelerations, which have the effect both of keeping the viewer from settling into a comfortable groove and of preventing the movie from feeling as long as it is despite its very methodical overall pace.

The soundtrack is another key weapon in The Shining’s arsenal, but one for which I’m not quite sure who deserves the credit. Certainly Walter Carlos’s unconventional and disturbing musical score is a masterpiece, but that’s far from the whole story. For one thing, I don’t know that I’ve ever seen another movie (apart from a few that eschew background music altogether) that makes so much use of the absence of music, or indeed of utter silence. The result is that non-musical sound effects become much more noticeable— and thus important— here than they are in most other films. Until I saw The Shining, it had never occurred to me that something like the sound of a Big Wheel’s hollow, plastic tires on a hardwood floor, alternating with a muffled hiss as they roll across carpet, could add so much to a movie’s atmosphere.

Then, of course, there’s the acting. This is something of a thorny issue in the case of The Shining, in that it is seized upon equally, and for the very same reasons, both by those who love the movie and by those who hate it. And as is only fitting, it is Jack Nicholson’s performance that serves as the centerpiece of both arguments. Nicholson is the main reason why Stephen King objects to the movie. His Jack Torrence is a semi-autobiographical character, a struggling young writer like King himself had so recently been (remember, we’re talking about the late 70’s here) who had been teaching English at a community college in order to make ends meet. Apart from his unconscious psychic abilities and a barely controlled drinking problem, King’s Jack is an entirely normal man. The horror of the novel The Shining is supposed to flow from the fact that even a man like Jack (neither better nor worse, morally speaking, than any other random person) can be perverted into a killer under the Overlook’s influence. But in Kubrick’s version, it’s impossible not to get a little bit concerned for Jack’s mental stability the very first time we see him. He doesn’t do anything bad at the job interview with Stuart Ullman, mind you, but something about him just isn’t right. Why? Because he’s played by Jack Nicholson, and something just isn’t right about him, either! But to me, the idea that the Overlook possesses a nearly unlimited power to inject its evil into the people who live within its walls is far less interesting than the idea that it draws out and amplifies whatever evil and craziness is already in you in order to feed itself on the negative energy thereby released. True, there is a certain element of that in King’s novel, but it is undermined there by the fact that Jack’s inner demons are just too small a facet of his personality to make it believable that the Overlook would prefer him to anybody else. Besides, if the hotel can work its magic on anyone who is unprepared to face it, provided that they have at least a faint spark of paranormal sensitivity to them, then why wouldn’t Wendy be driven crazy by it too? By making Jack such a sitting duck for the Overlook’s pernicious influence, Kubrick’s The Shining sidesteps the problem and allows for a far more satisfying treatment of the story.

And Jack Nicholson certainly does make his character seem like a sitting duck for the evil hotel. Obviously struggling not to look like a loony in the first part of the film, Nicholson finds his stride in the most aggressive manner when Kubrick turns him loose to portray Jack’s growing madness. The second half of the movie offers what must surely be the quintessential Jack Nicholson wildman performance, and even if he’d wanted to, there would be no way for Nicholson ever to live down the scene in which Wendy finally finds out what her husband has been writing so secretively in the huge room he uses as his study, or the later one in which Jack decides that enough is enough and comes looking for his family with an axe in his hands.

Truth be told, though, none of the cast seems quite at ease in the first third of the movie, and The Shining presents the curious spectacle of acting that improves as the film wears on. Shelley Duvall is singularly unconvincing at first, but like her costar, she seems to get more of a handle on the role once the Torrence family arrives at the Overlook. And while it seems to be little appreciated, there is one way in which Duvall’s casting as Wendy greatly improves the movie— not only is Duvall not Hollywood beautiful, it would take a charitable person indeed to describe her as even marginally attractive. With Wendy looking not that much different from the homely, dispirited housewives clogging the isles at your local Wal Mart (the few who aren’t also fat, anyway), she seems far more like a real person than she would have had Kubrick cast some turn-of-the-80’s California glamour queen instead.

Neither of the top-billed stars’ performances would come across nearly as well, however, if they didn’t have Danny Lloyd to play off of. In many ways, Danny Torrence is the axis around which the entire story turns, and if a movie adaptation of The Shining is going to work, it is imperative that the role be filled by someone who can really act. Considering the average state of child acting at all points in movie history, this is an awfully tall order, but Kubrick and company struck gold with Lloyd. He has a naturalness about him that I’ve only rarely seen in juvenile actors; he doesn’t fidget, his delivery is believable and no more mush-mouthed than the speech of any real-world six-year-old, and most importantly, he knows how to look scared. His physical acting would also be impressive coming from an actor two or three decades his senior. I can only wonder why The Shining didn’t lead Lloyd to a long career— at least one long enough to last him until puberty. By making Danny Torrence as real as either of his parents, he completes the triangle of relationships that enables us to care sufficiently about the central characters to fear for them when the Overlook hotel shows its true colors. And as the piece of the structure that was most likely to fail, he deserves a disproportionate share of the praise for making The Shining the brilliant film that it is.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact