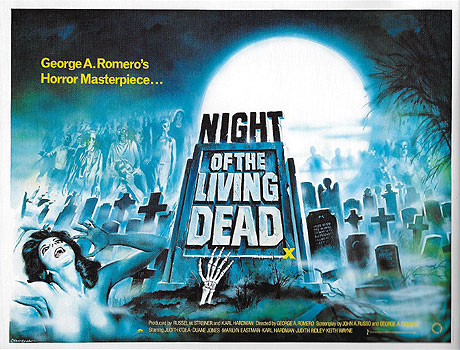

Night of the Living Dead (1968) ****½

Night of the Living Dead (1968) ****½

Okay, so Night of the Living Dead first shambled across the screen more than 30 years ago, and since then, pretty much everything there is to say about it has been said, much of it repeatedly. But you know what? I don’t give a fuck, because this movie is so goddamned important-- and so goddamned good-- as to merit everything there is to say about it being said again, and I propose to do more or less that right now.

In case you somehow missed this, the whole zombie movie thing starts right here. Sure, there were movies about zombies before Night of the Living Dead, but not a single zombie movie as we understand the term today, unless you count The Last Man On Earth. That movie had a lot to do with inspiring this one, and certainly there are any number of parallels between it and Night of the Living Dead, but as a modern zombie movie, The Last Man On Earth hasn’t really arrived. What it did do, though, was suggest a way to make zombies truly threatening. That film, as you may know, was based on the novel I Am Legend, by Richard Matheson, and its monsters are a kind of vampire. They drink your blood, they can be killed only in certain specific ways, and if they kill you, you become one of them. The big difference between the vampires of The Last Man On Earth or I Am Legend and, say, Count Dracula, is that there is nothing supernatural about the former. Their vampirism is merely a symptom of the disease that killed them in the first place. What all this has to do with Night of the Living Dead is the fact that director George Romero, who also co-wrote the film with John Russo, seems to have used The Last Man On Earth’s take on vampirism as a springboard for his re-invention of the zombie. The old zombie flicks (White Zombie or I Walked with a Zombie, for instance) forced themselves to rely heavily on the mere fact of the zombies’ existence to scare the audience, and generally made the witch doctor who created them the primary villain; let’s face it, after you get past the whole “these guys are dead, but they’re still walking around” thing, there’s nothing terribly alarming about re-animated stiffs being used as cheap labor in the sugarcane fields. What Romero and Russo did was give their zombies a veneer of Mathesonian vampirism. Like the creatures in The Last Man On Earth, Romero’s zombies are more like a biological plague than a personification of cosmic evil; there are only a couple of ways to kill them; and most importantly, they want you for their sustenance, and if they get you, you’re going to turn into one of them. That’s a fuck of a lot more threatening than something that just smells a bit funny while it picks the cotton.

The Last Man On Earth and I Am Legend are also echoed, if less clearly, in the main body of the film’s story, with the main characters set up in a fortified house, trying to fend off the bloodthirsty creatures surrounding it. But before we get to that, we are treated to one of the best set-ups I’ve ever seen in a horror flick. We start off with Johnny (Russell Streiner) and Barbara (Judith O’Dea), a brother and sister in their mid-twenties, driving through a country cemetery on an overcast evening. They have come to put a wreath on their father’s grave, but mostly what the two siblings do is bicker. Eventually, after the wreath has been laid, Johnny steers the conversation toward his and Barbara’s childhood-- in particular, Barbara’s childhood fear of the very graveyard in which their father is now interred. Doing his best impersonation of Boris Karloff, Johnny taunts his sister. “They’re coming to get you, Barbara... look! Here comes one of them now!” Johnny says, pointing to the only other person in the cemetery. Then, in a truly startling reversal of our expectations, Johnny’s words turn prophetic, as the man (who had been walking slowly in their direction) lunges at Barbara, pulling at her clothes and acting as though he were trying to bite her. Johnny rushes to his sister’s aid, and manages to distract her attacker long enough for her to run away, but the man struggles just as savagely with Johnny, ultimately cracking his head open on a nearby tombstone. The crazed man then goes after Barbara, who has taken refuge in her car. But the keys were in Johnny’s pocket, and now Barbara’s refuge has become a trap, as her attacker begins smashing at the windows with a large rock. This attempt to get inside the car is frustrated only when Barbara thinks to disengage the parking brake and put the car in neutral, allowing it to coast down the hill away from the killer. Even this stroke of inspiration wins her but a temporary respite, though, because the car grazes a tree on its way down the hill, and gets hung up on its trunk. Finally Barbara notices a farmhouse in the distance, to which she now flees-- and whose owners prove to have left the back door unlocked, luckily for Barbara.

Strange, then, that nobody should seem to be inside. The house obviously isn’t abandoned, but there is no sign of its owners’ presence. No sign, at least, until Barbara thinks to look upstairs. What she finds on the landing above indicates strongly that there’s more wrong with this particular corner of Pennsylvania than a rock-wielding maniac in the cemetery: at the top of the stairs is a dead body, its face almost completely skeletonized. This is about the point at which Barbara just shuts down. So far, she’s really been on top of things-- that trick with the parking brake, running to the house, trying the back door when the front one proved locked, thinking to use the phone to call for help (it’s not her fault the phone turned out to be dead), carrying a huge kitchen knife around with her while she checks out the house-- but that mangled body on the landing seems to have been the last straw for her. The moment she sees it, she flips out and runs screaming for the door, nevermind that the maniac is outside.

So it’s a good thing for her that the man with the tire iron she runs into on the porch is somebody else. That somebody else is Ben (Duane Jones, of Ganja and Hess), and he too has come to the farm house for shelter from lethal craziness. He had been at a nearby diner when an 18-wheeler smashed through the gas pumps in front of the restaurant, setting it afire and knocking it on its side. Then he noticed that the rig was being followed by a mob, which attacked both its flaming wreckage and the diner. Ben was lucky to be outside, sitting in an abandoned truck whose radio he was attempting to listen to. Otherwise, he would certainly have been killed by the mob when they massacred the diner’s patrons. But because he was in the truck, he had both shelter and a means of escape. He turned on its engine, and hauled ass down the road, straight through the group of glassy-eyed people who had surrounded him. Later, he pulled up to the house when he noticed the gas pumps in the front yard. (His tank was nearly empty.) When he discovered the lock on the pump, he came to the front door, hoping whoever was inside would have the key. Barbara, naturally, does not.

By this time, more and more weird-looking, shambling people are gathering around the house, and a few of them even find their way inside. They attack both Ben and Barbara, but Ben makes short work of them with his tire iron, and then locks all the doors and windows. He then sets about using any piece of wood he can find-- firewood, table legs, ironing board, even the doors inside the house-- to board up all means of ingress. Another look round the house turns up two very useful things: a rifle and a radio.

What the radio says is not good. It isn’t just rural western Pennsylvania that is suffering from unexplained outbreaks of mob violence, it’s the entire eastern third of the country, plus a small pocket of southeastern Texas. Not only that, it seems that, in every area affected by the phenomenon, the killers are eating the flesh of their victims. No one knows why. It is shortly after hearing this bit of bad news that Ben and Barbara learn that they are not alone in the house after all. While Ben is upstairs moving the dead body out of the way (and while we are noticing, as he does so, that its legs are perfectly intact despite the state of its head and upper torso-- sound like cannibalism to you?), two men burst forth from the cellar. The older of the two is named Harry Cooper (Karl Hardman). He and his wife, Helen (Marilyn Eastman-- she also plays a zombie!), and daughter, Karen (Kyra Schon), fled to the house after they were attacked and their car overturned by one of those homicidal mobs. Karen was injured-- bitten on the arm-- by one of their attackers, and now seems to be getting seriously ill. The younger man is Tom (Keith Wayne); he and his girlfriend, Judy (Judith Ridley), are from the area, and it was they who first sought out the house when they heard on the radio about the outbreak of killing.

And it is here that the main human drama of Night of the Living Dead begins, with the clash of wills between Cooper and Ben over how best to survive until the authorities come to the rescue. Ben believes that the house can be made into a serviceable stronghold, and that in any event, its spaciousness, the visibility afforded by its windows, and the contact with the outside world that its radio and TV set provide (to say nothing of the escape routes provided by its several doors) confer vital advantages in the face of the unexplained crisis. Cooper, on the other hand, is a passionate advocate of the cellar, where the single door greatly simplifies the task of defense, and whose underground construction makes it all but impregnable. Laid out in those terms, both sides seem to have some merit, but Cooper is such a colossal fuckhead that it doesn’t seem that way when he makes his case. This is going to be important later, trust me. Ben basically prevails, especially after Helen hears about the TV he found on the second floor. This TV has vital news for the refugees. The true nature of the rash of killings has finally come to light. It isn’t that some unknown force is making people crazy and forcing them to kill, it’s that some unknown force (possibly mysterious radiation brought back from Venus by a returning space probe) has been re-animating the dead and turning them into flesh-eating ghouls. But rest assured that the government is not taking this situation lying down. No sir. The Proper Authorities have discovered that the zombies can be killed by a shot or a solid blow to the head (“Kill the brain, and you kill the ghoul”), or they can be burned to death (“They go up pretty quick”). Also, a network of emergency shelters has been established throughout the affected region of the country, under the administration and protection of the National Guard, and all citizens are being urged to make their way toward the nearest one. This news gives Ben an idea. If keys to the gas pump outside could be found, he could refuel the truck, and all seven refugees could ride in it to the shelter in Willard. Tom locates the key, and he and Ben set off for the pump, while Cooper covers them by lobbing Molotov cocktails at the zombies.

But you know what they say about the best-laid plans. The first setback comes when Judy, who was never too comfortable with the idea of her boyfriend risking his life on this venture, runs out the door after him. This causes a couple of tense minutes, but ultimately nothing too serious. Not so the discovery that the key doesn’t fit the lock, and definitely not so Tom’s clumsiness with the hose after Ben shoots the lock away. Butterfingers manages to spray gasoline not only on the torch that Ben had used to fend off the zombies on their way to the gas pump, but more importantly all over the rear-quarter panel of the truck as well. Tom, thinking only of the danger posed by the fire raging close to the pump, jumps into the truck and speeds away, leaving Ben to try to bringing the fire under control with the heavy blanket from the truck’s bed. What Tom fails to grasp until it is much too late is that the fire on the truck’s fender is dangerously close to another tank full of gasoline. The truck explodes, with Tom and Judy inside, just moments after he realizes his mistake.

And now we come to Night of the Living Dead’s most famous scene, the Zombie Barbecue. While Ben makes his way back to the house, nearly the whole zombie army converges on the burned-out truck to get at Tom and Judy’s charred bodies. For the next five minutes or so, the camera stares unblinkingly as the ghouls feast, chewing in close-up on limbs and organs, squabbling among themselves over the best parts. 30 years’ worth of Tom Savini and the Italians have made this scene look a bit tame in retrospect, but in 1968, this was one of the ghastliest things ever to appear on a movie screen-- nothing in the Herschell Gordon Lewis canon comes close. The secret, of course, is real meat and organs, spare parts bought in bulk from Romero’s neighborhood butcher shop, with the black-and-white cinematography circumventing the age-old difficulty of formulating convincing fake blood.

It just gets worse for our heroes from there. Ben and Cooper begin fighting again the moment the former returns from his expedition. The fact that his idea served only to get Tom and Judy killed and eaten has undermined Ben’s moral authority a bit, but Cooper’s has been brought to an even lower ebb by his cowardly attempt to leave Ben to the zombies and lock himself away in the cellar. Then the power goes out, and all hell breaks loose. The zombies, emboldened by the darkness inside the house, their appetites whetted from devouring Tom and Judy, attack the house in a wave. Ben’s hastily erected fortifications are no match for the massed strength of the undead, and the doors and windows begin to give way. Cooper, shitbag that he is, picks this moment to resume fighting with Ben, going so far as to threaten him with the rifle. Ben seizes the gun away from him and shoots him in the gut, leaving him to crawl down to his beloved basement.

Meanwhile, the zombies are trying to pull Helen though the rapidly disintegrating front door. Amazingly, it is Barbara that comes to her rescue, but any benefit she reaps from saving the other woman’s life is purely karmic. As the door gives way, who should appear at the front of the zombie pack but Johnny! Barbara’s brother takes her in his arms, hauls her through the doorway, and then carries her into the carnivorous throng.

Now to the basement, to which Helen fled when Barbara bailed her out. It seems there’s nowhere safe left at all-- Karen has succumbed to her zombie-born infection, and is happily eating her father when Helen arrives downstairs. The girl then turns her attention to her other parent, stabbing her I don’t know how many times with a garden trowel in what I think is the movie’s hardest-hitting sequence.

And now it’s just Ben. He too makes his way downstairs, fighting his way past Zombie-Karen, and bars the cellar door behind him. He reaches the basement floor just in time to witness the resurrection of the Coopers. Good thing he still has that rifle, huh? After giving both zombies a bullet in the brain (three for his old buddy Harry), Ben sits down on the cement floor to wait out whatever remains of the night.

The next morning, the police and their deputies seem to be doing an admirable job bringing the situation under control. A heavily armed posse, the same one whose movements the reporters from the TV news had been following, has reached the fields surrounding the farmhouse. As they make their way toward the house, gunning down the zombies as they go, Ben hears the sound of their guns and dogs, and comes out of hiding to greet his rescuers. A fat lot of good it does him, too. One of the deputies sees him moving through the window, takes him for a zombie, and shoots him right between the eyes.

Thanks to Scream, even people who don’t watch very many of them now know that there are certain rules by which a horror movie can be expected to play. The true greatness of Night of the Living Dead lies in its utter contempt for all of them. From the moment when the first zombie splits Johnny’s skull on that headstone, it’s obvious that nobody in this movie is safe, that anyone can die at any time. Look at what happens to Karen; when not even the fucking child is safe, what the hell chance do the other characters have? The movie also bets heavily on your assessment of the characters’ personalities, and makes a point of proving you wrong on almost every score. At first, we expect Barbara to be the standard-issue ineffectual heroine, and we are surprised at her good sense and effectiveness early in the movie. Then, just when we think we’ve got her figured out again, she sees the body on the stairs, goes into shock, and becomes even more completely useless than our original snap judgement had predicted. But that’s nothing compared to the whammy that Night of the Living Dead lays on us regarding Ben and Cooper. We like Ben. He’s smart, he’s courageous, he’s a man of action, and when he explains himself, it makes good sense. Plus, he’s black, and particularly in 1968, that was a big deal. If you’re an egalitarian, especially a late-60’s liberal, seeing such an upstanding character played by a black man pushes your buttons. (For that matter, it also pushes your buttons if you’re a white racist, but we’re talking about a whole other set of buttons now.) Cooper, on the other hand, is a dick. He’s a coward, a bully, and a self-righteous pig, and when he makes his case, it all comes out as noise and bluster. (But note that Cooper is not a bigot. In fact, the issue of Ben’s race never once comes up in the movie itself, despite the fact that to make Cooper a racist would be the easiest, most obvious way to make us dislike him. I admire anybody who has the balls to forego the easy and the obvious-- that takes an uncommon measure of confidence in oneself and one’s creative vision-- and if I wore hats, mine would be going off to George Romero here.) The thing is, though, that Cooper is right and Ben is wrong. If everybody had listened to Cooper, and hidden down in the basement, they would have had, at most, a single zombie to deal with (Karen), and everyone would almost certainly have lived to see the next day. (Whether they’d have been safe from the trigger-happy posse is another matter...) But instead, they did what you or I probably would have done; they listened to Ben, and as a direct consequence, every single one of them died hideously. Even Ben.

But isn’t just the rules of the horror movie for which Night of the Living Dead expresses its contempt. This movie absolutely pisses all over just about every taboo that you could care to name. Let’s start with the biggie: cannibalism. Night of the Living Dead isn’t just about cannibalism (that had been done before on any number of occasions), it unflinchingly depicts the act itself right in front of the camera. Nobody had ever, and I mean ever, done that before. But there’s more taboo territory being explored here than just that. We’ve also got matricide. Holy shit, do we ever have matricide. When Karen takes that trowel and sticks it in her mother again and again and again and again and AGAIN, it even gets to me a little bit. And then there are the little taboos, like disrespect for the dead. I’m thinking not just of the abstract idea that the monsters in this movie are our own dead, but of the concrete ways in which Romero takes an axe to the reverence with which we expect the dead to be treated. When the characters are gathered around the TV set, watching the news explain the mess the eastern seaboard is in, the anchorman interviews a scientist on the subject of what to do to contain the zombie “epidemic.” The scientist’s advice: burn the dead. Take them out into the street and fucking burn them, ‘cause you’ve only got a few minutes before they’re going to get up and try to eat you. “The bereaved will have to do without the dubious comforts that a funeral service provides,” he says, “They’re just dead flesh-- dead flesh, and dangerous.” Let the funeral industry chew on that one for a while.

Night of the Living Dead is also notable for the appearance, already in his first real movie, of a theme to which Romero would return again and again during his filmmaking career: the Proper Authorities are not your friends. Early on, we have the newsmen interviewing a general and two scientists on the subject of what could have caused the zombie plague. The scientists believe the radiation from the returning space probe to Venus is responsible, but the general is adamant that no such thing has been proven. Again, the scientists, who do this sort of thing for a living, have a professional opinion regarding the origins of the zombie plague, and the general, who makes his living thinking of ways to kill Russians, weighs in and says that nothing has yet been proven. And then there’s the posse. The novelization of the screenplay that John Russo published a few years later soft-pedals this (which says to me that this distrust for authority is Romero’s alone), but here in the original movie, the men assembled by the police chief to protect the citizenry from the ghouls are just a bunch of hillbilly thugs with itchy trigger fingers. Not only do they shoot Ben, they do so from halfway across a field, at a range from which nobody could possibly distinguish a zombie from a live human, especially if the person/zombie in question was standing well back from the window in a house! And it isn’t just the deputy, either-- the police chief himself gives the order to shoot Ben, it apparently never having occurred to him that somebody in the house might still be alive. This idea would resurface, in ever more strident terms, in the sequels to Night of the Living Dead-- Dawn of the Dead and Day of the Dead-- but it would get perhaps its most eloquent treatment in The Crazies/Codename Trixie. If you want to see Romero really run with this particular ball, check out that last one.

Really, there’s only one thing wrong with Night of the Living Dead. Simply put, it is a victim of its budget. The usual mark of the cheap film, the terrible special effects, is surprisingly not in evidence here. (Surprisingly, that is, until you stop to think about how cheap old meat is in the grand scheme of things.) Instead, it shows in places that can actually damage the movie. In the stock-music score, for example, which doesn’t always quite fit the action to which it is set, and more importantly, in those scenes where it is evident that an imperfect take was accepted because the production’s shortness of cash made retakes a luxury that could be afforded only in the event of a glaring screw up. It’s not enough to make Night of the Living Dead any less of a classic, but it is enough to take it down half a notch from the apex of the craft.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact