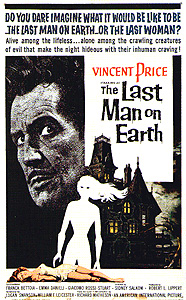

The Last Man on Earth / Wind of Death / L'Ultimo Uomo della Terra / Vento di Morte (1964) **½

The Last Man on Earth / Wind of Death / L'Ultimo Uomo della Terra / Vento di Morte (1964) **½

When Richard Matheson’s I Am Legend appeared in 1954, it was a vampire novel like no other. Matheson’s minor stroke of genius was to remove the vampire from the matrix of myth and legend that had always surrounded it, and approach the subject instead from a modernist, scientific perspective. Yes, there were still garlic and mirrors and wooden stakes, the undead still ventured out of their hiding places only at night, and they didn’t much care for crosses, but the underlying reasons for all these things couldn’t possibly have been farther from the ones handed down in folklore. What’s more, the apocalyptic circumstances in which the novel was set echoed the atomic Armageddon that was never far from anyone’s mind in those days. I Am Legend thus accomplished what most of the best, most lasting horror stories do, taking an age-old fear and updating it for a world so transformed as to threaten it with irrelevancy. And while its inward-looking, one-character narrative would have presented a tremendous challenge to any filmmaker seeking to adapt it, the potential rewards of success would surely have been more than enough to inspire the daring. Yet the only attempt to film I Am Legend during the decade that gave birth to it ended in total failure. Hammer bought the rights in 1957, and hired Matheson himself to write the screenplay for the movie they intended to call Night Creatures. The British Board of Film Censors pitched a fit, however, and sent the studio a letter warning that Night Creatures would be banned if, in fact, it was produced. Now Hammer had been flouting— and flaunting— the X-Certificate for a good two years by this point, but a ban was another matter altogether, and the project was quietly abandoned. Thus it was that the world would have to wait a full ten years for an I Am Legend movie, and while AlP’s Italian-produced The Last Man On Earth is a decent enough film, I can’t help but look at it and think, “Man— Hammer would have done this so much better…”

Of course, Hammer wouldn’t have put Vincent Price in the starring role, which could very well have been to their version’s detriment (unless, of course, they’d used Peter Cushing instead...). Price plays Dr. Robert Morgan, a former medical researcher who now finds himself apparently the last living human on the entire planet. His house is a strangely forbidding place for the home of an affluent suburban scientist, what with its boarded-up windows, locked garage (this was 1964, you know), and incongruous bits of industrial machinery scattered about inside, but Morgan has very good reason for doing things the way he does. The two dead bodies out on the front porch, for example. They hadn’t been there the day before, and it’s the way they arrived that explains why Morgan lives like this. After making the rounds of his place— listening to his short-wave radio to make sure there’s still nobody broadcasting, taking down the shattered mirror and the dried-out wreaths of garlic cloves on the outside of the front door, checking the gas in the generator, making note of which windows need new boards nailed over them— Morgan hoists the corpses into his station wagon (thinking something to himself about how “they” kill the weak among themselves when no other prey is available), and drives them to the outskirts of town, where he tosses them into a vast, flaming pit. One assumes the fuel for those flames is an unfathomable number of bodies like the ones our hero just fed into them.

As Morgan carries on his day, we come closer and closer to learning just what the Last Man on Earth is taking such obsessive precautions against. His first stop is a grocery store, where he seems to have rigged up another generator to keep the refrigerators running. There, Morgan helps himself to a bushel of fresh garlic. He also snaps up some small mirrors to replace the broken one on his door. Then, after returning home, he fires up his lathe, and gets to work fashioning pointed stakes, thinking all the while about “them.” Finally, with a fresh supply of stakes, Morgan checks the map of the city that he has tacked up to the workroom wall (much of which is covered with indecipherable notations in heavy, black ink), plans his itinerary for the afternoon, and goes out hunting. With the methodical regularity of the scientist he once was, Morgan searches each building in his chosen sector of town, and hammers his homemade stakes into the hearts of the cadaverous-looking people he finds in the darkest corners of each, resting safely out of reach of the sun. And when sunset comes, Morgan goes home once again, where he drinks himself to sleep while blaring his record player in a futile attempt to drown out the sounds of the undead banging on his locked doors and boarded-up windows, hungry for the blood of the living man they know is inside.

So how, you ask, did the world get to be this way, overrun by nearly mindless vampires, and how did Robert Morgan manage to be the one man lucky (or unlucky) enough to survive to see it? Three years ago, the lab where Morgan and his best friend, Ben Cortman (Giacomo Rossi-Stuart, from Knives of the Avenger and The Night Evelyn Came Out of the Grave), worked was commissioned by the government to study a mysterious plague that was decimating Europe, Asia, and Africa. All that was known definitively was that the disease agent was borne on the wind, and that its onset was marked by increasing debility during daylight hours, accompanied by blindness in its terminal phase. But there were rumors— rumors Morgan refused to credit— which had it that anyone who died of the disease would rise up from the tomb as something very much like the vampires of ancient legend. Cortman, who was less quick to dismiss the word on the street, found it very interesting that the government insisted upon confiscating and burning the bodies of all plague victims after the disease spread to the United States. And Cortman, as it happens, was right; perhaps his insistence upon leading the vampire mob that now besieges Morgan’s house each night is his way of saying “I told you so.” Morgan didn’t listen, however, and it wasn’t until after both his daughter, Kathy (Christy Courtland), and wife, Virginia (Emma Danieli), had both succumbed that the scales dropped from his eyes. Morgan, you see, tried to keep Virginia’s body out of the hands of the authorities. Rather than see her tossed into that pit outside of town, Morgan drove her out to the country and buried her himself. But the next evening, Virginia came home...

Now this scenario would get old fast if Morgan remained alone in his battened-down house, doing his damnedest to ignore the vampires by night and running search-and-destroy missions in the city by day, so it’s only to be expected that the man’s routine is about to get shaken up a little. One day, Morgan sees a poodle out on the street. Yeah, I know— who the fuck wants a poodle?— but the point is that this is the first living thing other than himself that Morgan’s seen in over three years. His initial efforts to catch the dog and make a pet of it don’t pan out, though, and it isn’t until a subsequent evening, when he finds the animal lying injured in his back yard, that Morgan is able to get the poodle into his house. By that point, it’s too late. The dog’s injuries were caused by one of the vampires, and now the dog itself is infected. Morgan stakes it, and buries it in the park the next day.

It’s while Morgan is engaged in that errand that an even more surprising development comes to pass. Morgan sees a woman (Franca Bettoia, from Duel of the Champions and Attack of the Normans) watching him. In broad daylight. She’s almost as hard to talk into coming back to his place as the dog was, but eventually it sinks in with her that Morgan, if he’s out and about while the sun is up, can’t be one of the vampires. The woman introduces herself as Ruth Collins, and her story in the years both immediately before and immediately after the advent of the vampire plague are pretty much the mirror image of Morgan’s. But Morgan still can’t shake the feeling that something isn’t right about her, that she somehow still carries the disease. After all, she could scarcely have been bitten by a Panamanian bat while serving in the Canal Zone during World War II (the event that, for lack of a better explanation, Morgan credits for his own immunity to the vampire virus). As a matter of fact, he’s right, and she isn’t the only one of her type in the city. Morgan’s lab wasn’t alone in searching for a cure for the plague. Somewhere, another doctor discovered a drug that, while neither curing nor inoculating against the disease, did prevent the worst of its symptoms from appearing. Like insulin for a diabetic, regular injections of the drug keep the disease in remission, and allow its carriers to live almost normal lives. They’ll still be violently allergic to garlic, and they’ll still find it more comfortable to live a nocturnal lifestyle, but they won’t die, they won’t lose their minds, and they won’t become blood-drinkers. Unbeknownst to Morgan, there is an entire society of these half-vampires all over the city, and he’s been staking and killing them right along with the full-fledged undead in his daily patrols downtown. And now, a posse of those half-vampires is on its way to Morgan’s house to eliminate this deadly scourge that stalks by sunlight...

So what is it about The Last Man on Earth that makes me wish Night Creatures had gotten made? Mainly it’s this— The Last Man on Earth presents Vincent Price actually acting for once, in one of the best, most subtle performances of his career. And yet everything around him is so flat and lifeless that all that effort on his part was mostly wasted. Screenwriters Logan Swanson and William P. Leicester stick much closer to Matheson than their successors did in writing The Omega Man, but they leave out most of the novel’s best tricks. A major part of the book concerns the protagonist’s efforts to figure out the hows and whys of vampirism, and not a bit of that stuff makes it into the movie. The screenplay also never bothers to delve into the relationship between Morgan and the undead Ben Cortman, nor does it even touch on an issue that gives the novel much of its distinctly Mathesonian flavor. In the novel, Robert Neville (for that is the character’s name in the book) is constantly tormented by his stifled sex drive. At 36, Neville is in the prime of life, but until Ruth comes along, the only women he ever has contact with are the undead. The vampire women know this, too, and while the men beat on the doors and walls of his house with fists and cudgels, they parade in front of the planked-over windows, striking lewd and salacious poses in an effort to coax him outside. I can see why this wouldn’t make it past the censors in 1964, but cutting this angle has the effect of flattening out the story’s human dimension, and the film is much the worse for it. Another serious— if proportionately minor— oversight concerns the absence from The Last Man on Earth of vampire animals. They play little real role in the book, but the importance of the dog Morgan/Neville adopts is entirely lost without at least establishing their existence. Finally, the climactic revelation that Ruth isn’t quite human after all, and that Morgan has, without even realizing it, become a figure of mythic evil for a society he never knew existed is seriously shortchanged here. True, Matheson didn’t develop it as much as he should have, either, but part and parcel of the whole concept of adaptation is the opportunity it affords to shore up the weaknesses of the original.

The other millstone around The Last Man on Earth’s neck is director Sidney Salkow. Salkow’s drab, businesslike style is completely wrong for the movie. Only during one scene— the flashback to the night Virginia came home to her husband— does he seem to get the idea through his head that he’s directing a horror movie. There’s nothing frightening about the rest of the vampires, nor even about the half-vampire death squad that descends upon Morgan’s house at the conclusion. Worse still, Salkow evidently could think of no better way to establish what was going on inside Morgan’s head than constant and distracting voice-over narration. It may crap all over the source material at every turn, but The Omega Man displays a much deeper understanding on its creators’ parts of the requirements of cinema— while it scarcely works at all as an adaptation of I Am Legend, it works much better as a movie in general than does The Last Man on Earth. And so it is that I pine for Night Creatures. The Last Man on Earth takes the novel seriously, but consistently stumbles as a film; The Omega Man tosses the novel out almost completely and substitutes a solidly entertaining Something Else; the Arnold Schwarzenegger vehicle the script for which has been bouncing around on the internet for the last several years... well let’s just say I sincerely hope it never gets made.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact