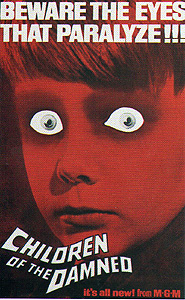

Children of the Damned (1963) ***½

Children of the Damned (1963) ***½

I guess it’s true that there’s a first time for everything. Generally speaking, I hate— hate— sequels that pay no heed whatsoever to their predecessors. At best, I might appreciate them for their absurdity in other respects (think War of the Gargantuas or The Return of Doctor X), but I honestly can’t think of even a single sequel that completely disregarded the original film which I considered to be genuinely good upon having seen it. Until now, that is. Sure, Children of the Damned plays as much like a remake of Village of the Damned as it does like a sequel, and sure, that does annoy me just the slightest bit. But because it also expands upon its predecessor in a satisfying, logical way without directly undermining it except in some of its tiniest particulars, it somehow manages to get around my disdain for sequels that have little or no regard for their source material.

This time, we go about our introductions a little differently. Psychologist Thomas Lewellin (Ian Hendry, from Theater of Blood and Repulsion) has brought his friend and roommate (and possibly even boyfriend— these two can act an awful lot like a married couple when they want to) David Neville (Jonathan Frid look-alike Alan Badel, from The Medusa Touch), himself a geneticist, to the elementary school where he works in order to show him something truly amazing which Neville’s experience in his field might be able to shed some light on. Routine IQ testing on the incoming class has revealed that one of the new boys, Paul Looran (Clive Powell) is quite literally freakishly intelligent. To cite one particularly striking example, he is able to solve a fiendishly complex three-dimensional puzzle (completion times under seven minutes are considered exceptional) in 37.5 seconds! Neville knows just as well as Lewellin how utterly, uniquely outlandish this is, and at his suggestion, the two scientists pay a visit to the boy’s home to interview his mother, Diana (The Legend of Spider Forest’s Sheila Allen). Ms. Looran is not happy to see them. She exhibits no interest in her son’s exceptionality, she refuses to take any tests herself, and she absolutely bridles with rage at Neville’s questions regarding Paul’s absent father. Then, after the two researchers leave empty-handed, Diana turns to her boy and spitefully tells him, “They know about you. They’ll get you this time, and I’ll help them— do you hear me?— I’ll help!!!!” But before she can do any such thing, Diana seems to slip into a trance. She turns around, walks right out the apartment building door, and goes wandering off in the middle of the street until she is run over by a motorist. When Lewellin and Neville come to see her at the hospital, she has a seemingly impossible story to tell them: she was still a virgin when Paul was born.

Now with Diana in the hospital with more broken bones than I’d care to count and no father on the scene (whether or not one chooses to accept the injured woman’s incredible claims), Lewellin thinks it would be best if he and Neville temporarily took Paul into their custody, at least until such time as one or another of the boy’s relatives can be reached. But when they stop by the Looran place that evening, they find that Diana’s sister, Susan Eliot (Barbara Ferris) is already there. Nobody called her— she just had a sort of feeling that Paul needed her, and came to her sister’s flat. And fortunately for the two scientists, Susan proves rather more cooperative than her sibling; when Neville suggests that she and Paul come to meet with the UNESCO agent who controls his funding, she doesn’t see any harm in the idea.

Thus it is that Susan is within earshot when Neville’s boss drops a bombshell even bigger than that represented by Paul’s existence in the first place. It seems that there are five other children Paul’s age, hailing from countries all over the globe, who share his remarkable abilities. In fact, when they are administered Lewellin’s IQ test, all five score— to the point— exactly the same as Paul. Needless to say, this ought to be impossible, and a cursory investigation into the backgrounds of Mark (Frank Summerscale), Nina (Roberta Rex), Rashid (Mahdu Mathen), Mi Ling (Yoke-Moon Lee), and Aga Nagolo (Gerald Delsol) only deepens the mystery. Like Paul, all five of the other children were born of utterly unexceptional mothers, while no sign of any father can be uncovered. UNESCO is able to convince the families of each child to bring them to their respective embassies in London, so that Lewellin and Neville can study them, but the scientists don’t remain in control of the situation for long. Once the governments of China, India, Nigeria, the US, and the USSR fully grasp the abilities of their native prodigies, agenda-bearing G-men start hovering around Lewellin’s lab, aiming to bring their superkids home. For our purposes, the governments of the world will mostly wear the face of British secret agent Colin Webster (The Night Caller’s Alfred Burke), who despite working for a cute and cuddly parliamentarian democracy, is frankly and unapologetically ruthless in his approach to Paul and his fellow prodigies— if they cannot be controlled and monopolized by Britain and her allies, then they must be destroyed at the earliest opportunity.

The one thing nobody involved in the situation seems to have reckoned on is the children themselves. As intelligent as they are, they must obviously have some idea what the adults around them are up to, and indeed, scarcely a moment elapses between Webster’s arrival at the Looran place with a warrant authorizing him to take Paul into official custody and the boy’s escape from right under the noses of his would-be keepers. Paul spends the rest of the morning rounding up the rest of the children from their embassies, and leading them to an abandoned, ruined church. Paul then uses his formidable psychic powers to lever Susan into sneaking over to the church, too, where he and the rest of the children press her into service as their liaison to the adult world. This leads to a tense and lengthy standoff when the authorities figure out where Paul and the gang are hiding out, and dispatch a company of soldiers to surround the church.

Chances are the first feature of Children of the Damned that will strike any viewer who has seen its predecessor is that fact that no mention is ever made of the Midwich children or their counterparts in small towns scattered all over the world. This is the film’s most serious break with Village of the Damned; despite a few small circumstantial differences, the advent of Paul, Mark, Nina, Rashid, Mi Ling, and Aga Nagolo bears more than a passing resemblance to that of the Midwich children, and one would scarcely expect an incident so serious that the Soviet government would order the nuclear incineration of a town on their own home soil to have faded from official memory so quickly. The other points of discontinuity are relatively minor next to this. The current crop of superkids don’t display the strong physical resemblance to each other that was depicted in Village of the Damned, they exhibit an odd reluctance to speak which certainly did not characterize the Midwich children, and the circumstances of their births is somewhat different— each child appears to have been unique in his or her home town, and at no point is there any mention made of the mysterious outbreak of unconsciousness that hit Midwich on the day that its abnormal children were conceived. But because neither film ever offers a straight answer regarding the origins of the children, these differences are easy enough to overlook. If they are the product of some kind of intelligent design— as the first movie strongly implied— then we may assume that the intelligence behind that design simply learned from its mistakes and adopted a more subtle approach this time around. But the apparent ignorance of the characters in this movie regarding the events of the last one is a bit harder for me to swallow.

So what enables me to get it down in the end? Simple... One of my favorite things about Village of the Damned is the way it portrays its nominal heroes in a light that is often far from favorable. That goes double for Children of the Damned, where the Machiavellian maneuverings of the British, Soviet, American, Chinese, Indian, and Nigerian governments are the driving force behind most of the plot. Though the scene-by-scene business of the film mostly takes place on a smaller scale with the efforts of Susan, Lewellin, and Neville to understand and, where necessary, protect Paul and the other children, the greater geopolitical implications of the children’s birth into a world in the grip of the Cold War cast their shadows over everything that goes on. There are a few instances in which this sense that the real action is unfolding just out of sight turns into a handicap, especially once the confrontation between the authorities and the kids at the church settles into a state of stalemated siege, but for the most part, it heightens the movie’s power by creating an aura of doom around the proceedings. After we’ve had a couple of chances to see Webster and his counterparts in action, it comes to seem as though everyone who might want to find a resolution that involves neither the eventual extinction of the human race nor the immediate extermination of the children is utterly powerless to shift events from either of those courses. Along with its more insightful treatment of official reaction to the emergence of a new breed of superhumans, it is the filmmakers’ success in convincing their audience early on that nothing good can come of any of this that enables Children of the Damned to overcome my usual distaste for strongly discontinuous sequels.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact