Death Ship (1980) -***

Death Ship (1980) -***

I would love to have been a fly on the wall at the Avco-Embassy offices during the meeting between the studio execs and producers Derek Gibson and Harold Greenberg, of the Canadian Bloodstar Productions, that resulted in the creation of Death Ship.

“Hmmm…” I can envision the bosses saying, “The Shining on a freighter, eh? I like it.”

“We’ll need to get Leslie Nielsen if it’s a movie about a ship.”

“Nah— he’s too expensive now. Besides, He’s doing those movies that make fun of the old shipwreck and plane-crash pictures. People would think it’s a comedy.”

“Well what about that other guy? You know— he did the ones with the airplanes instead of the ocean liners.”

“George Kennedy?”

“Yeah, him! He’d be perfect, and he’s been real cheap ever since that Japanese thing with the germs and the A-bombs flopped.”

“Ooh! Wait! Can we make the ghosts on the ship Nazis? I love a good Nazi picture…”

“Say… that’s brilliant! We’ll do The Shining on a ship, and the ghosts’ll be Nazis, and we’ll get George Kennedy to play the captain. We can’t lose with this!”

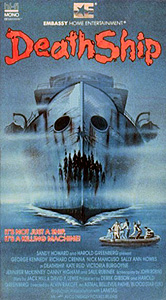

Well, no. Actually, they could lose, and they did. And while chances are that if you were around in the mid-1980’s, you vividly remember the box art from the videotape, with the skull-like bow of the evil freighter looming out of the fog to menace the life raft bobbing beside its forefoot, chances are also that you passed Death Ship by with an intuition that it couldn’t possibly be as good as it looked. It isn’t, but it sure is a lot of fun if you’re in the mood to watch an honestly pretty decent idea go hopelessly awry.

Somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, an old freighter (but not nearly as old as the script would have it— from the size and the architecture, I’d say we’re looking at a ship from the turn of the 60’s) cruises at speed through the foggy twilight. The vessel is poorly maintained, with blistered paint, rusted plating, and rancid, dusty grease clotting most of the fittings— curiously, the pattern of rust on the bow forms the vague suggestion of a human face. Stranger still, though the cabins and corridors echo to the sound of human voices barking orders and acknowledgements in excitedly clipped German, there is no visible sign of anybody actually being aboard. To all non-auditory appearances, the huge VTE steam engines are running all by themselves. Elsewhere— someplace where it’s the middle of the night— an ocean liner under the command of one Captain Ashland (Kennedy, from Strait-Jacket and The Boston Strangler) makes its stately way across the sea. This is Ashland’s last voyage; the company for which he works has forced him into retirement on the grounds that he is much too difficult, rude, and personally unpleasant to serve as the captain of a pleasure vessel, and they have further saddled him with the burden of devoting his final cruise to familiarizing his intended replacement, Captain Trevor Marshall (Richard Crenna, of Wait Until Dark and Leviathan), with his ship. Little does either captain realize that the ghost freighter (which is still sailing under the waning sunlight of late afternoon) has detected the liner, and has adjusted its course and speed for a ramming attack. While Ashland and Marshall are down in the passengers’ lounge doing the meet-and-greet thing, the radar officer (it’s nighttime where they are, remember) picks up the freighter (nope— still about 5:30 where it is) on his scope, and brings it to the first officer’s attention. The freighter matches every evasive maneuver, and gives no reply to any attempt at communication. Scant minutes later, the ghost ship (still under weak sunlight) rams the liner (still in full darkness) dead amidships, and the latter vessel sinks with cataclysmic speed.

It would appear that only one life raft’s worth of survivors made it off of the liner. Captain Marshall is among them, as are his wife, Margaret (Sally Anne Howes, from Dead of Night and the 1972 TV version of Hound of the Baskervilles), and children, Robin (Jennifer McKinney) and Ben (Danny Higham, of Bedroom Eyes). Also aboard the raft are a junior-grade lieutenant named Nick (Nick Mancuso, from Nightwing and Black Christmas), his passenger fuck-buddy, Lori (Secrets of a Door-to-Door Salesman’s Victoria Burgoyne), a man called Jackie (Saul Rubinek), and an elderly woman named Sylvia Morgan (Kate Reid, of Virus and The Andromeda Strain); a few hours after the wreck, they pick up the half-drowned Captain Ashland, too. Things are looking pretty bleak for the castaways. There was no time to scrape together more than the smallest quantity of the most basic provisions, and the Atlantic is not peppered all over with small but minimally habitable islands the way the Pacific is. Unless a ship or an airplane comes along within the next day or so, they’re all pretty much fucked. Of course, even when a ship does appear on the horizon, they’re still pretty much fucked, because the vessel in question happens to be the ghost freighter that ran their ship down the night before. (Absurdly, the freighter has suffered no damage from the collision. To put this into perspective, consider that when the battleship Wisconsin [which was built much tougher than any merchant ship] accidentally rammed the destroyer escort Eaton [which was barely one-fortieth the Wisconsin’s size] in May of 1956, the force of the impact shredded about 25 feet of the Wisconsin’s bow.) Whatever malign spirits inhabit the freighter are perfectly content to let Lori, Sylvia, Jackie, Margaret, and the kids come aboard, but the officers have a rougher time of it. The gangway collapses under their feet, and even after Lori tosses down a rope ladder from the deck, the men are nearly killed when a jet of fuel oil blasts out of the scuttle above them, making it nearly impossible to maintain a grip on the ladder. Then a cargo derrick snags Jackie by the ankle in a loop of cordage, swings him out over the side of the ship, and drops him into the water to drown or be ground up by the propellers, whichever he’d prefer.

That’s about the sort of hospitality that everybody can expect from the Death Ship sooner or later. Nick is also attacked by a derrick, although he lives to tell the tale. Sylvia eats a piece of hard candy she finds in the ship’s pantry, and rushes through about 40 years’ worth of aging and decomposition in as many seconds. (In the “credit where credit is due” column, I must admit that this is certainly the first time I’ve ever seen a horror movie use cursed hard candy to dispatch one of its characters.) Lori is assaulted with blood from a showerhead in the cabin she shares with Nick, which evidently kills her despite the seemingly self-evident fact that getting hosed down with somebody else’s blood is generally more icky than lethal. (Lori sure as hell doesn’t die from AIDS, if you know what I’m saying.) And while all that’s going on, the spirit of the vessel’s original captain tries to interest the delirious Ashland in signing on as his successor. Then Trevor and Nick find the cabins buried deep in the ship’s interior, where the Nazi crew used to torture and execute the enemies of the Reich, and things turn really ugly.

Here’s one to ponder: With Gestapo office buildings and detention complexes scattered all over Germany and the occupied territories, and with a vast network of prison camps covering all of Eastern Europe, what possible reason could the Nazis have had for wasting 15,000 tons or so of scarce shipping capacity on a big, floating torture chamber that would operate thousands of miles from the military intelligence agencies on whose behalf its crew would be working? A big, floating torture chamber, I might add, which could relay home the secrets it extracted only by means of radio signals that the Allies would be sure to intercept and decode, which would be vulnerable to attack by two of the world’s three most powerful navies, and for the defense of which not even a single warship could be spared! (Though the storied exploits of individual units like the Bismarck and the Graf Spee tend to obscure this point, even the Italians had a more powerful surface fleet than Nazi Germany.) As a horror movie premise, an industrial-age reinterpretation of the legend of the Flying Dutchman has much to recommend it, but screenwriter John Robbins obviously didn’t think things through very carefully while penning Death Ship. To all appearances, he just ruminated for a minute or two over the question of what would make a ship turn evil, and then said to himself, “The Nazis tortured people, right? The Nazis had ships, right? So surely the Nazis would torture people on ships— it makes perfect sense.” Except, of course, that it doesn’t.

Meanwhile, in its capacity as a rip-off of The Shining, the main impression which Death Ship leaves is that director Alvin Rakoff is no Stanley Kubrick. (Neither, for that matter, is George Kennedy much of a Jack Nicholson, Danny Highman much of a Danny Lloyd, or Richard Crenna much of a Scatman Crothers.) Though Rakoff has, in the haunted freighter, a setting fully equal to the Overlook Hotel in terms of menace and foreboding, he is never able to generate a scare to match even the least of what we get from the Kubrick film, even though he is not shy in the slightest about stealing Kubrick’s tricks. The main problem is that Rakoff doesn’t really seem to know why he’s making off with the pilfered merchandise. Notice, for example, that Death Ship makes just as much use as The Shining of near-subliminal images that foreshadow the eventual fates of its characters, but that the recycled device fails utterly because it has no underpinning in Death Ship’s story. When we see flashes of that tsunami of blood pouring out of the Overlook’s elevator shaft, or of the word “redrum” scrawled in lipstick across the bedroom door, it’s because we’re eavesdropping on Danny Torrence’s psychic premonitions. There’s no reason at all for the quick peek we get here at Syliva’s prematurely rotting face, at Lori getting soaked by a rain of blood, or at Nick flailing helplessly in a cargo net full of human bones. To borrow a turn of phrase from Cold Fusion Video’s Nathan Shumate, this is cargo-cult filmmaking— the reverent appropriation of elements from more accomplished movies, divorced from any apparent understanding of the function those elements were designed to perform. Those flash-forwards in The Shining must have done something, and Kubrick stuck them here, here, and here, so Rakoff dutifully does the same thing and then sits back to wait for the gods of the celluloid scare to pour out their mana upon his work. Unsurprisingly, they never do, and the beautiful part is that Rakoff gives no indication that he recognizes even that.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact