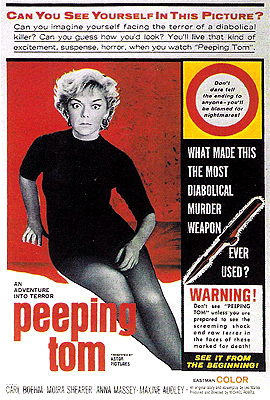

Peeping Tom (1960) ****˝

Peeping Tom (1960) ****˝

There is surely no more potent indicator of the disrepute in which horror movies have been held for most of their history than the fact that up until comparatively recently, it was quite possible for a director to destroy his career by making an unusually accomplished— indeed, even brilliant— film in the genre. The classic example is Tod Browning and his post-Freaks career nosedive, but perhaps even more striking is the case of Michael Powell and Peeping Tom. Together with longtime partner Emeric Pressberger, Powell spent the 40’s and 50’s directing such highly regarded movies as Black Narcissus, The Red Shoes, and Pursuit of the Graf Spee. The Archers, as Powell and Pressberger called themselves, won industry awards and critical acclaim in roughly equal measure, and looked likely to remain major players on the British film scene for the foreseeable future. Then Powell uncoupled from Pressberger to make Peeping Tom for Anglo Amalgamated. It was— and remains— among the most powerful and imaginative horror movies ever to come out of Great Britain, and it sparked such a firestorm of loathing and indignation from critics and press that Powell couldn’t get a job in his home country apart from the occasional television episode for the rest of the decade. The conventional story has it that Powell’s fortunes improved after he came to the attention of Francis Ford Copolla and Martin Scorsese, who made a great deal of noise championing him during the late 60’s and early 70’s, but even a cursory glance at Powell’s filmography suggests that he actually drew very little benefit from his supposed rehabilitation. Powell directed all of two movies in the 70’s— one of them a deeply obscure children’s film and the other a slightly modified repackaging of a documentary he had made all the way back in 1936— and none at all after 1978. Such were the rewards which the horror genre used to dangle before the faces of its most talented practitioners.

Eighteen years before Halloween, Peeping Tom begins with an extended, single-take, first-person rendering of a woman’s murder. A man with a 16mm movie camera cradled in the breast of his coat turns the device on, and from then forward, we watch through the camera’s viewfinder as the man accosts a hooker, follows her up to her room, and kills her by some means which will not become clearly apparent until much later in the film. We see the killer reach past the camera’s lens with his right hand, and we see that a light source of some kind is trained on the prostitute’s face just before she dies, but that’s all. (Well, okay. So there’s one more thing we learn as a consequence of this scene: in London in 1960, you could get laid for just two quid.) Immediately thereafter, we see the whole scene played out again, but this time we’re in the killer’s home screening room, watching as he watches what the camera recorded of the girl’s demise. If the murderer’s body language is anything to judge by, he regards his crime with considerable ambivalence despite the nearly obsessive degree of preparation which seems to have gone into it.

The next day, a young man named Mark Lewis (Unnatural’s Carl Boehm) watches from the street outside the dead hooker’s flat as the police haul her body away. He’s also filming the scene, and we’d know he’s lying to the one detective who asks him which newspaper he works for even if we didn’t recognize both the distinctive lens housing of his camera and the furry lining of his coat from the opening murder. Mark then leaves the site of his crime to pursue what will gradually be revealed to be his secondary line of work. A newsagent named Peters (Bartlet Mullins, who can be briefly glimpsed in tiny roles in Trog and The Creeping Unknown) pays Mark to help him produce the kind of magazines that give him his most profitable business— “The kind with girls on the front covers, and no front covers on the girls.” Mark’s assignment for the afternoon is to take some pictures of the newsagent’s favorite model, Milly (Pamela Green, from Legend of the Werewolf and As Nature Intended), and a new girl named Lorraine (Susan Travers, of The Snake Woman and The Abominable Dr. Phibes), the latter of whom can be photographed only from certain angles or from the neck down because of the terrible scar that mars the right side of her upper lip. Lewis, however, finds Lorraine’s scar fascinating, and he shoots some footage of her damaged face for his own use.

Mark lives in a large tenement house that was originally a single, rather grand residence. On his way home, he peers in one of the ground-floor windows at his neighbors, the Stephenses, who are throwing a birthday party for 21-year-old Helen Stephens (Anna Massey, from Bunny Lake Is Missing and The Vault of Horror). Helen sees Mark looking in on her party, recognizes him as the reclusive young man who lives upstairs, and rushes out in an attempt to entice him to join the fun. Mark is much too shy to go for it, and is visibly uncomfortable with receiving any sort of attention from a pretty girl who isn’t separated from him by a camera’s viewfinder. Nevertheless, the two end up spending some pleasant time together, as the girl brings Mark up a slice of birthday cake an hour or so later. During the conversation, Mark reveals several unexpected things about himself and his background. First, he’s actually a professional cinematographer, drawing a regular paycheck from a regular movie studio and everything. Secondly, he’s the owner of the house, which he inherited from his father; he rents out most of the rooms simply because he doesn’t bring home enough money to finance the upkeep of the place by himself. Most importantly, Mark’s dad was none other than the renowned experimental psychologist A. N. Lewis, author of a comprehensive multi-volume treatise on the biological, physiological, neurochemical, and affective aspects of fear in the human mind. And as Helen learns when she talks Mark into showing her some of his vast collection of home movies, Mark himself was his father’s most important lab rat. Dr. Lewis filmed or otherwise recorded almost every second of Mark’s childhood, producing the most detailed longitudinal study of human personality development ever mounted. He also regularly conducted experiments on his son— especially experiments designed to help him puzzle out the secrets of fear. Is it any wonder Mark came out as deeply fucked up as he is? Helen finds Mark’s old home movies intensely disturbing, and the story behind them so frightening in its implications that she almost seems to be angry at Mark for telling her about it. But even so, she likes her strange young landlord quite a lot, and she begins spending a great deal of time with him, even despite the suspicions of her bitter, blind, and perpetually inebriated mother (Maxine Audley, from Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed and Bluebeard’s Ten Honeymoons), who doesn’t trust Mark for reasons she can’t convincingly articulate.

Meanwhile, Mark is gearing up to kill again. At the moment, he’s employed as a focus puller on the set of some stinky comedy produced by Don Jarvis (Michael Goodliffe, of The Day the Earth Caught Fire and To the Devil… a Daughter), directed by Arthur Baden (Esmond Knight), and staring Diane Ashley (Shirley Anne Field, from Horrors of the Black Museum and These Are the Damned). Ashley’s understudy (what she needs one of those for is never really explained) is a girl named Vivian (Moira Shearer), whom Mark has promised to help bring out from under the star’s shadow. The plan, as Lewis has explained it, is to sneak onto E Stage after hours one night to shoot a test reel demonstrating Viv’s ability to convey heavy-gauge emotion. Needless to say, the emotion Mark plans to film Viv in the throes of is fear, and he means to do it by subjecting her to the same treatment as that hooker he killed earlier. This second crime is even more baroque than the first, however, for Mark deliberately hides the body in a place where it’s sure to be found over the course of the next day’s shooting, and he surreptitiously films the set as Diane Ashley and one of the supporting players open up the prop trunk in which the dead girl’s body lies concealed. And interestingly enough, he cooperates so fully with the subsequent investigation by Chief Inspector Gregg (Jack Watson, of The Gorgon and From Beyond the Grave) and Detective Sergeant Miller (Nigel Davenport, from No Blade of Grass and Phase IV) that one gets the feeling he actually wants to be caught. On the other hand, an encounter with Helen’s mother a few nights later suggests that maybe Mark only wants to be caught under a certain set of highly specific circumstances. It’s also an open question just how his developing romance with Helen herself fits into Mark’s lunatic program.

One of the earliest horror movies of the “lifestyles of the sick and twisted” school, Peeping Tom also stands as one of the very best. Certainly it is among the most thematically rich films of its type, and one of the very few horror movies that can support the kind of Freudian interpretation so beloved of professional film scholars without eliciting the usual outpouring of egregious overreaching and whole-cloth horseshit. After all, if Freudian analysis can’t help us interpret a movie about a voyeuristic psychopath who was set on the path to violent madness by an obsessively controlling father, himself a credentialled psychologist, then it’s even more worthless as a critical framework than I generally believe. Indeed, while the shitstorm was raging around him, Powell went so far as to deny that Peeping Tom was a horror movie at all, claiming instead that it was nothing more nor less than a commentary on the exploitation and indeed sadism inherent in any form of human interaction that involves watching and being watched. Obviously there’s a certain amount of disingenuousness there, but Powell unquestionably meant it when he said that there was far more going on in Peeping Tom than in the average fright flick. Most obviously, it stands as an indictment of the mental health industry, which was just coming into its own in its modern form in the late 50’s and early 60’s. Powell and screenwriter Leo Marks are quite blatant about equating psychoanalysis with voyeurism; not only has Mark’s psychiatrist father created a monster precisely by spying on every second of the boy’s upbringing in the name of science, but Mark himself reveals at one point that Dad was actually working on a book about voyeurism when he died. Finally, in the move’s most openly Freudian turn, it gradually comes out that Mark’s crimes actually stem from his warped desire to complete the work started by his father, both in the sense of carrying his fear research to its logical conclusion and in that of bringing to a close the meticulous cinematographic record of his life. Mark is thus at his sickest when he has most completely internalized his father’s aims. The unmistakable implication of the story is that psychiatry is at least as effective in making insanity as it is in curing it.

There is another level, however, at which Peeping Tom attacks a different form of socially acceptable voyeurism— that to which the motion picture industry owes its existence, and to which Powell and his cohorts therefore owe their livelihoods. Mark, after all, is a cameraman by trade, and in his hands, the camera is quite literally an instrument of death. What’s more, as we see when we get to watch Don Jarvis and Arthur Baden in action, Mark is hardly the only sadistic scopophiliac employed by his studio. Even more telling, in its subliminal way, is an especially devilish piece of casting. In Mark’s old home movies, his father is played by none other than Powell himself, and the young Mark is played by Powell’s real-life son! It’s about as clever a way to tie together the two main aspects of the film as any I’ve seen, although it is concededly one which will likely be lost on a large fraction of the audience.

What I can’t imagine being lost on anybody is the extraordinary effectiveness of Peeping Tom as the horror film its creators tried so hard to pretend it wasn’t. The movie makes for an interesting parallel with Psycho. Both were released in 1960, both represented an effort by a highly respected directorial heavyweight to step at least a little ways outside his usual territory, and both attempted to play the Sympathetic Monster card with a killer whose outward appearance belies an evil nature imparted to him by an overbearing parent. Both even take the risk of incorporating a massive, glutinous lump of exposition into their conclusions. But for all the similarities between the two films, Peeping Tom is greatly superior in almost every department. It may not have anything to equal the suspense of Psycho’s first act, but it is much more aggressive overall than its American contemporary, coming across like a little piece of the 70’s that mistakenly arrived about fifteen years too soon. Mark is more compelling as a sympathetic villain than Norman Bates, partly because we know approximately what he is about almost from the start (and therefore have more time to explore the contradictions of his dual nature), but mostly because he is a genuinely tragic character, totally unable to fix any of the things he knows are wrong with him, and motivated as much by a desire to protect Helen from himself as by his compulsion to visit violent death upon all the other young women in his life. Peeping Tom is also thought-provoking in a way that Psycho doesn’t even attempt, delving into its killer’s origin to a degree and with a persuasiveness that few other movies of its type can match. I found myself rooting for Mark’s recovery under Helen’s unconsciously therapeutic influence, even though such a thing would be obviously impossible, and would more importantly have a serious detrimental impact on the story. It isn’t often that a movie makes me care so much about one of the characters that I actively long for it to sabotage itself on his behalf. I can only marvel once again at the timorous obtuseness of British audiences and critics (the latter especially) at the turn of the 60’s.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact