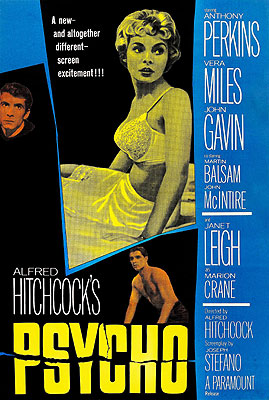

Psycho (1960) ***½

Psycho (1960) ***½

As I said earlier, in my review of Homicidal, I do not share the reverence with which it is customary to regard this flick. Don’t get me wrong-- it’s a damn good movie, and the first half of it kicks ass in ways that most horror movies lack the imagination even to dream about. But there are two major obstacles to my appreciation of Psycho (and if you’re one of Earth’s four living Robert Bloch purists, you’ll probably find a third-- more on that later). The first of these obstacles isn’t Hitchcock’s fault, and had I been born 30 years earlier, it would have been no obstacle at all. I am, of course, about to restate a point I already made when talking about Homicidal, that Psycho is a movie that lives and dies by its two big surprises, and that, 40 years after the film’s release, those all-important scenes offer no surprise at all. At the age of ten or so, when I had not yet seen Psycho, I had seen the shower scene, and I knew who the real killer was. This a priori knowledge threw a major monkey wrench into the mostly elegant machine that Hitchcock built here; because I knew exactly what was coming, the movie’s two best tricks seemed to fall flat when I at last got around to watching it in my early teens. I reiterate that I cannot and do not blame the movie for this-- it is merely the victim of its own success. But I can and do fault the esteemed Alfred Hitchcock for the way he progressively loses control of the movie after the death of the detective Arbogast, finally allowing it to come apart at the seams in what is surely one of the most grievously bungled anticlimaxes that I have ever witnessed on the movie screen. Then, to compound the error, Hitchcock follows up with an excessively tidy, false-feeling resolution that concentrates-- in the clumsiest possible manner-- all the exposition related to the character of Norman Bates (which could have and should have been snuck piecemeal into the main action of the film) into a single indigestible mass.

But before we get to that, let’s talk about the good part, because it’s a damn fine good part, and had the whole movie managed to maintain its level of quality, Psycho would fully deserve the bowing and scraping of its many worshipful fans. Once upon a time in Phoenix, Arizona, there lived a woman named Marion Crane (Janet Leigh, whose lengthy prior career has been all but totally eclipsed by this one role, and whose equally lengthy post-Psycho career probably deserves to be) who loved a man she was unable to marry. What’s the hang up? I have no idea. The obstacle to Crane’s marriage to Sam Loomis (John Gavin, from House of Shadows and Jennifer) forms the pivot on which much of Bloch’s novel turns, but it is never clearly explained here. All I can tell you is that it has something to do with Loomis’s ex-wife. One day at her shitty job, her real estate agent boss brings in an ostentatiously wealthy client who plunks down $40,000 in cash to buy his daughter a house as a wedding present. The boss asks Marion to take the money to the bank that very day; he doesn’t want a wad of that magnitude lying around the office unguarded over the weekend.

And this is what sets the wheels moving in Marion’s head that will ultimately lead her to a very bad end indeed. It occurs to Marion that with that kind of money, she and Sam could just run away together. They could go anywhere, and if they played their cards wisely, they could be almost untraceable-- nobody but Marion’s younger sister even knows she’s seeing Sam. So Marion never does go to the bank. Instead, she heads back to her apartment, packs her bags, and sets off across the desert, bound for Loomis’s town. Along the way, there are some close calls with a policeman who stumbles upon her car parked by the side of the road (she’d been sleeping in it), and rapidly comes to suspect that Marion is up to something. She even ends up trading in her car for a used one in the hope of throwing him off the scent. (By the way, have a look around the used car lot where she makes the transaction-- have you ever seen so many ‘59 Edsels in one place in your life?) But Marion’s real problems don’t start until the evening after she runs off with the money, when the reduced visibility attendant upon a mammoth thunderstorm causes her to miss an important fork in the road, leading her off the main highway down a road to nowhere that almost nobody uses anymore.

Just about the only thing on this road is a run-down motel operated by a young man called Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins, but you already knew that). Marion stops in at the motel to stay the night and, she hopes, get directions back to the highway so that she can continue her journey. After she gets her room, she spends a fair amount of time talking to Bates, who seems as though he hasn’t had a chance to talk to anyone, let alone a good-looking woman, in ages. The man is shy, awkward, and socially inept, but he nevertheless has a certain naïve charm about him, and it quickly becomes apparent that there is at least one person with whom he has had contact recently. Indeed, that seems to be Norman’s entire problem, for that one person is his jealous, overbearing, possessive mother. His jealous, overbearing, possessive, insane mother, who takes such a dim view of her son having a life apart from her that she goes apeshit when Norman invites Marion up to the house for dinner. Marion hears the two shouting at each other in the house all the way down the hill in her motel room.

So Norman adopts a compromise strategy, and brings dinner down to her. She eats and chats some more with the strange little recluse in the parlor behind the motel’s office, and with each exchange of words, Norman seems a bit more peculiar. He’s a taxidermist, and in fact spends just about all of his time that is not occupied with the hotel or his mother stuffing and mounting birds. He has never had a girlfriend, nor any real friends at all for that matter. (“A boy’s best friend is his mother,” he says ominously.) And he knows very well that his mother is sick in the head, but he refuses to have her institutionalized out of a sense that to do so would be to betray her for all the effort she expended raising him after the death of his father. In fact, Marion’s conversation with Norman takes a turn for the ugly when she suggests to him that perhaps the old lady ought to be “put somewhere.” The vehemence of Norman’s refusal would be almost scary if he weren’t such a skinny little twerp. But the outburst is a short one, and he apologizes to Marion-- a bit too late to keep her interested in talking to him, though. She heads back to her room and leaves Norman to close up the office for the night.

But Norman doesn’t leave the office after he shuts it down. Instead, he creeps over to the wall that separates it from Marion’s room, lifts aside one of the picture frames, and spies on her preparations for bed through a small hole drilled in the wall. That’s pretty bad, but it’s nothing compared to what’s coming. A bit later, as Marion takes a shower, Norman’s mother sneaks into her bathroom (we see her only in silhouette), and stabs the other woman to death with a carving knife. When the old lady returns to the house (the camera stays outside, at the bottom of the hill) Norman sees her covered with blood, and knows immediately what she’s done. He spends the rest of the night cleaning up the motel room and trying to dispose of the evidence, even going so far as to bury Marion’s car in the swamp near the motel (we must be in California now; I can’t imagine there being even a single swamp in Arizona).

About this time, people are beginning to notice Marion’s absence. A week later, when there’s still no sign of her, her sister, Lila (Vera Miles, of Mazes and Monsters and A Strange and Deadly Occurrence), decides to pay a visit to Sam Loomis on a hunch that she may have gone to him. She knows about the missing money, of course, though she doesn’t quite believe that Marion deliberately stole it. In any event, Sam has no more idea-- less, in fact-- than Lila what has become of Marion. And after a few hours of denials, he even manages to sell his innocence to Milton Arbogast (Cape Fear’s Martin Balsam, who began his movie career with 12 Angry Men, and ended it with such tawdry crap-fests as Death Wish III), the private investigator hired by Marion’s boss, who followed Lila to Sam. Arbogast is nevertheless sure that Marion had meant to go to Sam, and he spends the next day trying to figure out what stopped her. His investigations lead him to the Bates Motel, where his nosiness gets him a date with Mother’s knife.

Finally, Lila and Sam come to the conclusion that if you want something done right, you have to do it yourself. They go to the county sheriff (John McIntire) to tell him about Marion, and about the unexplained disappearance of Arbogast when he went to check out the motel. When they tell the sheriff that when they last heard from the detective, he was about to go talk to Norman’s mother, the sheriff drops the movie’s second big bomb. Norman has no mother. The old lady has been dead for ten years-- hell, the sheriff was a pall bearer at her funeral. When Lila and Sam go to the motel to see for themselves (posing as motel guests), Lila manages to sneak into the Bates house while Sam keeps Norman occupied at the office. What she discovers there leads us to Psycho’s second most famous scene, as Lila finds Mrs. Bates sitting in a chair in the basement, her back turned to her. She turns the chair around, and stares into the empty eye-sockets of the old lady’s taxidermized carcass, just as Norman, who had earlier ended his chat with Sam by means of a solid blow to the other man’s head, appears at the top of the basement stairs-- in drag and brandishing a carving knife! But apparently Norman didn’t whack Sam quite hard enough, because the latter man follows him through the door and restrains him, forcing him to the ground before any harm can come to Lila.

In the ill-considered conclusion, a psychiatrist takes up the last five minutes of the film blathering about multiple personality disorder, explaining how Norman came to be the way he is. He tells Lila and Sam that Norman hasn’t been fully in control of his own person since, at least, the day of his mother’s death, and that the tragedy of losing the old lady so traumatized him that the only way he could cope was to re-create her in his own mind. Over time, the piece of Norman that was standing in for his mother became stronger, until it finally became so strong as to eclipse Norman completely. The next-to-last shot has Norman sitting alone in a holding cell, talking to himself in his mother’s voice. “I’ll show them what kind of person I really am,” s/he says, “I’m not even going to swat that fly...” The film ends with a close-up of Norman, his lips parted in the most sinister smile you’ve ever seen, fading into a shot of the tail of Marion’s car, as some powerful machine drags it from its watery grave.

Up until the death of Arbogast, Psycho really is one of the best horror movies I’ve ever seen. The restricted budget and the consequent limitation on the film’s length impose a discipline on Hitchcock, giving him little room to dilute the impact of his tremendous directorial talent by squandering his ideas on unproductive eye-candy. (To see what happened when Hitchcock’s tendency to do just that was given free reign, have a look at The Birds.) Marion’s flight from Phoenix with the embezzled money is intensely suspenseful, and her scenes alone with Bates are equally gripping. Even after 40 years, the famous shower scene remains a model of the proper use of implication in the horror movie-- it tricks you into thinking you’re seeing more than you really are, rather than trying to get away with not showing anything. (I could write a quite lengthy essay on this subject alone. This is not the place for such indulgence, however, so I will limit my comments to this: The shower scene is often held up as a paragon of tasteful restraint in counterpoint to the excesses of the Wes Cravens and Herschell Gordon Lewises of the world, but when you get right down to it, you’re being shown quite a lot. “Yes,” your eyes tell you, “Janet Leigh is, in fact, naked.” “Yes,” your eyes tell you, “that sure is a big fucking knife.” You can count the stabs, should you feel yourself so motivated, and you can plainly see all of that blood running down the drain. And then there’s that sound, the knife plunging again and again into that poor, abused casaba melon. Are there any latex appliances? No, not a one. Do we even see the knife touch Janet Leigh’s body? Never. But this remains a far cry, in terms of explicitness, from something like The Blair Witch Project. To equate to the level of restraint displayed by that movie, Marion’s murder would have had to have taken place entirely offscreen, while the camera stared vacantly past the open bathroom door. Can you imagine the lameness of this scene had it been shot that way?)

A close corollary to the effectiveness of the shower scene in purely technical terms is the incredible dramatic boldness that Hitchcock and screenwriter Joseph Stefano displayed by putting it where it is. In Robert Bloch’s novel, Mary Crane is killed a mere 70 pages into a 200-plus page book. Not only that, those 70 pages make clear in no uncertain terms that the novel will be about Norman Bates. He is the first character to whom Bloch introduces us, and he is the character with whom we spend the most time. That’s not the case, though, with Hitchcock’s movie. Here, all signs point to Marion Crane as the film’s protagonist, and her demise, fully halfway into the film, would have been jarring in the extreme had I not known beforehand that it was coming. This is the only one of the many changes that Stefano made to the story that I believe improved it in any meaningful way. (I also think Stefano’s decision to play up Norman’s taxidermy hobby was a good one, though it added comparatively little to the film’s effectiveness as a whole.)

The other truly great thing about Psycho is the music. Bernard Herrmann’s fantastic score is what the music from nearly every other horror movie made in the last 40 years wants to be when it grows up, and I can think of only a handful of other movies whose scores fit them so perfectly (Halloween, perhaps; maybe Aliens; certainly Godzilla: King of the Monsters and John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing). The fact that the slashing violins of the shower scene have become something close to a universally recognized musical cue for murder by sharp instrument speaks, I think, for itself.

But the brilliance of the first half of the movie only makes its later descent into chaos that much more tragic. I suspect the root of the problem is that Psycho probably ought to have been about five or perhaps ten minutes longer. With the death of the detective, Psycho abandons its confident, measured pace, and begins galloping headlong toward a conclusion that the exposition we have thus far seen is ill equipped to support. And that headlong rush only accelerates as the climax nears, until Lila’s discovery of the stuffed Mrs. Bates, Norman’s appearance in the guise of his mother, and his final defeat at the hands of Sam Loomis-- what ought to have been a gripping, suspenseful scene-- is compressed into mere seconds and dismissed, as though the whole business were only an afterthought, and the real climax had come with the sheriff’s revelation that Norman’s mother is dead. That this highly unsatisfying sequence is followed up by a scene in which a doctor stands around explaining what we just saw is an even bigger mistake. There is no reason why Stefano couldn’t have dropped enough hints at how seriously fucked up Norman was into the main action of the story to enable the audience to put all the pieces together for themselves once the central revelation that Norman and his mother were one had been made. I refer you to Bloch’s version of the story as an illustration of how this could have been handled (although I must point out, in all fairness, that Bloch’s Psycho also ends with a pontificating psychiatrist, a development that is even more puzzling in its context because the treatment of Norman’s character throughout renders it totally unnecessary).

And that brings me to the last point I want to make about Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho-- the striking differences between it and Robert Bloch’s Psycho. I’ve already mentioned a few points of divergence-- the earlier placement of Mary Crane’s murder in the book, Bloch’s more detailed explanation of the reasons why Mary and Sam do not simply marry (which has the effect of making Mary’s embezzlement of the $40,000 more understandable). But more important than these is the difference between the two portrayals of Norman Bates. Hitchcock’s Bates is, to begin with, much younger than Bloch’s, and he is of a very different physical type. But there is also a profound psychological difference, in that the Norman Bates of the novel is clearly a dangerous man even before it is revealed that he occasionally dresses up as his dead mother and kills people. The novel spends a lot of time inside Norman’s head, and it is not an attractive place, let me tell you. Bloch’s Norman is also much smarter, and much more calculating than the one in the movie, and combined with the fact that he is much more clearly nuts, this makes it a bit more believable that he would try to “protect his mother” from the consequences of “her” crimes. Finally, I have a feeling that Hitchcock’s decision never to show us Norman’s mother except in silhouette (apart from one very brief, long-distance shot of him carrying her out of her bedroom) would have made me suspicious, even had I not already known the truth about the Bateses. There is no such problem in the novel, which devotes a great deal of space to scenes in which Norman and his mother interact.

Psycho is still a fine movie. When it works, it works as few such films ever have. The problem is that it spends so much time in its crucial final phase not working. The errors of its creators are far from fatal, and the strength of its first two thirds would have been enough to earn it classic status even in the face of far worse climactic fumbling, but I stand by what I said in my review of Homicidal-- it falls a bit short of deserving all of the jizz that movie critics over the years have blown over it, and I’d still rather watch William Castle’s cheap knock-off any day of the week.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact