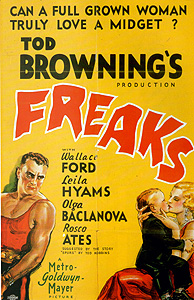

Freaks / Nature’s Mistakes / Forbidden Love (1932) ****

Freaks / Nature’s Mistakes / Forbidden Love (1932) ****

I’ve never been much of a Tod Browning fan; I tend to regard him as a director with more vision than talent, who occasionally got really, really lucky, and pulled together a noteworthy film (though I confess to never having seen any of the silent movies he made with Lon Chaney). I also generally think MGM should have stayed the hell out of the horror genre, with which its leadership was obviously never comfortable in the first place. So it’s very odd, then, that one of my favorite horror films of the 1930’s should be one that Browning directed for MGM. I think the secret to the artistic success of Freaks/Nature’s Mistakes/Forbidden Love (we’ll talk about its striking lack of success on other fronts later) is that Browning faced almost no interference from the studio while he was working on it. The gigantic heaps of money that Browning’s Dracula had pulled into Universal’s coffers the year before convinced the studio heads at MGM that the director had the magic touch, and they were so eager to get a piece of that action for themselves that they were willing to trust Browning to a degree that was almost unheard of in Hollywood— not just in those days of powerful studios, but in any period of American cinema history. The result of that extraordinary hands-off approach was a movie the likes of which audiences in the English-speaking world had never been faced with before, and for which they were totally unprepared.

At its core, Freaks is a perfectly ordinary revenge drama. What makes it totally unique in the long history of film is its unusual setting, and the unprecedented way in which that setting is depicted. The story unfolds within the Rollo Brothers’ traveling circus, but the central characters are, for the most part, not the clowns, acrobats, and animal trainers with whom most circus movies concern themselves, but the freaks of the circus sideshow— the midgets, dwarves, pinheads, conjoined twins, and other human oddities who make their livings less through their special talents than through their sheer physical abnormality. And, of the greatest importance in this case, who are played here by real life midgets, dwarves, pinheads, conjoined twins and other human oddities! The midget Hans (Harry Earles, from Browning’s earlier The Unholy Three) is engaged to be married to another sideshow midget named Frieda (Daisy Earles, Harry’s real-life sister), but he has fallen in love with Cleopatra, the circus’s star acrobat (Olga Baclanova, of The Man Who Laughs). Cleopatra initially encourages Harry’s fawning over her because she finds the notion of a midget in love with a woman of normal stature to be exceedingly funny. Given enough time, Cleopatra would surely have tired of the joke, and left her tiny suitor to return to his fiancee and beg her forgiveness. But it isn’t long before Cleopatra learns that Hans possesses a surprising amount of money, with which he is extremely generous, and this leads her to go on stringing her hapless lover along.

Meanwhile, circus strongman Hercules (Henry Victor, from King of the Zombies and the 1916 version of The Picture of Dorian Gray) has broken up with his girlfriend, Venus (Leila Hyams, of The Thirteenth Chair and Island of Lost Souls, whose character’s role in the circus is left unexplained— although it somehow involves fishnet stockings and patent-leather hot-pants with appliqué flames on the ass), who has finally gotten sick of him mooching off of her while he brandishes his biceps at every attractive girl who comes down the pike. While Venus seeks comfort in the arms of Phroso the clown (Night of Terror’s Wallace Ford, who isn’t nearly as annoying here as he was in The Mummy’s Hand), Hercules sets his sights on Cleopatra. This is an awfully good deal for the parasitic strongman, who now gets to exploit Hans’s largesse toward the acrobat. And though the two schemers are fairly circumspect at first, they gradually become less so once they realize that Hans will shower even more money and gifts on Cleopatra if he perceives that he has competition. Finally, Frieda, who still loves Hans deeply despite the heartbreak of losing him to Cleopatra (perhaps she is simply realistic enough to recognize that Hans will inevitably come crawling back to her sooner or later), becomes so upset at the way Hans permits the acrobat to take away his dignity that she goes to Cleopatra herself. Frieda tells her that she knows the other woman is only in it for the money and a laugh at Hans’s expense, and she warns Cleopatra to leave Hans alone. But Frieda miscalculates, in that she assumes Hans has told Cleopatra about the enormous fortune he has inherited from a relative in Germany, and makes reference to it in her talk with her rival. Cleopatra, however, had no idea where Hans was getting his money, nor did she have any clue how much of it there really was. Now that she knows the midget is filthy rich, she goes so far as to propose marriage to him (not that she means to stop seeing Hercules or anything, mind you), so as to give legal legitimacy to her parasitism. And Hans, the poor fool, falls for it, hook, line, and sinker.

The marriage of Hans and Cleopatra marks the turning point of the story. Cleopatra has no friends in the circus other than Hercules, so the great majority of the guests are freaks from the sideshow. At the reception dinner afterwards, the dwarf Angeleno (Angelo Rossitto, from The Corpse Vanishes and Mesa of Lost Women, the only one of the movie’s sideshow performers who can really act) suggests that Cleopatra be inducted into the family of freaks. In the movie’s most famous scene, Angeleno fills an enormous cup (it’s nearly as big as he is) with wine, and then passes it around the table for everyone to drink from while the assembled freaks chant, “Gooble gobble, gooble gobble— we accept her, we accept her. Gooble gobble, we accept her— we accept her, one of us.” Cleopatra is the last one to whom the cup passes, and by the time it reaches her, she has had a couple minutes for it to dawn on her that she’s being made an honorary freak. Now Cleopatra is thoroughly sloshed by this point, and with her judgement thus impaired, her calculated interest in playing along isn’t strong enough to overcome her visceral revulsion at the idea that these creatures are talking about welcoming her into their little demimonde. Cleopatra flips out, and runs screaming from the table, shrieking curses at the “filthy, slimy freaks!!!!”

The very next day, after a desperate and only partly successful effort to patch things up with Hans, Cleopatra sets in motion a plan to poison her husband and thereby get her hands on all his money. Once her scheme comes to full fruition, she will presumably marry Hercules in Hans’s stead and retire with him from the circus. But fortunately for Hans, and unfortunately for Cleopatra and the strongman, the bride’s little performance at her wedding has made the freaks of the sideshow extremely suspicious of the acrobat’s motives, and when she begins poisoning Hans, her every action comes under the closest scrutiny from the other freaks. Even Phroso and Venus, the freaks’ greatest friends among the physically normal performers in the Rollo Brothers’ circus, are in on the effort to trap Cleopatra, and after a few days of watching, that trap springs shut. One night, while the wagons of the circus slog down an unpaved road through a vicious thunderstorm, the freaks gang up on their tormentors and wreak their vengeance. Hercules winds up with a knife in his back, while the freaks make Cleopatra “one of us” in the most literal possible sense. We see her years later, a legless, mute monstrosity, exhibiting herself in a different sideshow as the Chicken Girl.

There’s only one real scare scene in Freaks, but it’s enough to merit the movie’s inclusion in the horror genre all by itself. The revenge of the freaks is one of the most harrowing things to be committed to film in the nearly four decades between the end of the silent era and explosion of hyper-intense horror that began with the release of Night of the Living Dead in 1968. The brief shot of the armless, legless Prince Randian squirming through the mud toward Hercules with a stiletto in his teeth remains an image of extraordinary horrific power even today. But this scene would not work nearly as well as it does were it not for the extremely sympathetic, humane portrayal Browning gives the freaks throughout the rest of the movie. No matter how drastically deformed or mentally deficient they may be, all of the freaks in this movie are presented as human beings no different, morally speaking, from you or me. The real monsters here are the physically normal— indeed, even supernormal— Cleopatra and Hercules. The horror in the climactic revenge scene springs less from the deformity of the perpetrators than from the fact that these are docile, gentle people, accustomed to getting the short end of life’s stick, who have finally been driven to violence by Cleopatra’s iniquity. We all know that, when victims become victimizers, they are apt to show as little mercy as they themselves have received, and so we instinctively realize that these unfortunate people, who have spent their lives having their fundamental humanity denied them— even, in many cases, by their own families— will become an implacable engine of vengeance now that the tables have been turned.

Freaks was mired in controversy from the moment it hit the screen. The still mostly powerless Hays office predictably pitched a fit when they got a look at it. Test audiences found the movie so upsetting that MGM recalled it, and trimmed nearly twenty minutes of footage, including some particularly nasty bits of the climax and the kicker ending. (The original cut of the film had the tree under which Cleopatra tries to hide from her pursuers falling on her legs after getting struck by lightning, leaving her helpless to escape as the freaks swarm over her. The subsequent sideshow scene had Hercules exhibiting himself alongside her as a castrato soprano.) Even then, it caused such a ruckus that it was pulled from circulation after a mere three weeks. In Great Britain, the Board of Film Censors banned Freaks outright, and the interdict stood until well into the 1960’s. The climax was part of the problem. Keep in mind that Dracula, which was too demure even to show the count emerging from his coffin, was considered a frightening film at the time. Freaks offered a much stiffer jolt of horror than any movie yet made outside of Continental Europe. But it was the use of dozens of real freaks in the cast that really got to people. The physically normal are outnumbered in the cast by at least three to one, and the catalogue of deformities on display is so broad that midgets and dwarves come to seem utterly ordinary by the second reel. The sideshow, for all its popularity, was not, by the early 1930’s, an entertainment that “polite” people admitted to indulging in, so the mere fact of this movie’s cast was shocking in and of itself. And at the same time, there were those who thought the film cruelly exploited its stars; I find it hard to understand how an attentive viewer who got past the admittedly lurid advertising campaign could form such an opinion, but then again, it is a well-established trait of cultural crusaders that they feel no compulsion to actually see, read, or listen to whatever work of art it is they’re campaigning against. The result of all this outrage and indignation was virtually the end of Tod Browning’s career. The director whose reputation had won him unprecedented freedom from studio interference had made himself a pariah by exercising that liberty. Browning would continue to make movies (he directed The Devil Doll as late as 1936), and those movies continued to reflect faint glimmers of his distinctive artistic vision, but his masters in the boardroom would keep him on such a short leash that he never again came up with anything to compare with Freaks. The bitter irony of it all is that this movie is now considered a classic even by the intellectual descendants of the people who so stridently condemned it when it was released. I tell you, there’s just no damn justice in this world.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact