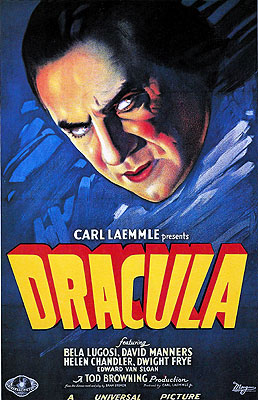

Dracula (1931) *½

Dracula (1931) *½

There is simply no denying the importance of Tod Browning’s Dracula. It was the first horror talkie to deal expressly with the supernatural, it put Universal Studios on the map as Hollywood’s foremost purveyor of the macabre, and with his performance here, its star created one of the most memorable screen icons of the genre. To this day, despite the literally dozens of people who have portrayed him over the past 70 years, most people, when they talk about Count Dracula, are talking about Bela Lugosi. But to say that a film is important is not necessarily to say that it is good, and if ever evidence were needed to support that assertion, this movie here would be a good place to start.

Cinematic adaptations of the written word almost always involve baffling re-workings of the source material, and Bram Stoker’s most famous novel has endured more tinkering than most in its various translations to celluloid over the years. Even as early as 1931 (earlier, in fact, as we shall see whenever I get around to F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu), the screenwriters were already hard at work shuffling the relationships between Dracula’s characters to no good purpose. Arthur Holmwood and Quincy Morris are gone altogether (and I say good fucking riddance in the latter case); Dr. Seward is now Mina’s father, and Lucy (whose last name has been simplified to “Weston”) has been reduced to the status of some random chick with whom Mina hangs out on occasion. The only change that accomplishes anything in terms of making the story run more smoothly concerns the character of Renfield. In the novel, you may recall, Renfield was a patient of Seward’s who, for no reason worthy of the name, had some sort of bond with Dracula that caused him to eat bugs. The present movie, on the other hand, opens with Renfield (Dwight Frye, who later appeared in The Vampire Bat and Frankenstein) traveling to the castle of Count Dracula to discuss the lease of some real estate in London, a task which fell to Jonathan Harker in Stoker’s version of the story.

Renfield ought to have started worrying on the carriage ride into the Carpathians. Some of his fellow passengers spent the journey muttering about vampires and Walpurgis Night, and how they plan to spend their evening locked in their houses, praying for the intercession of the Virgin Mary. But even when the coach stops to let off passengers, allowing Renfield a chance to horrify both his coachman and a small group of peasants by announcing his plans to ride on to the Borgo pass and thence on to Castle Dracula (and an unusually cooperative bunch of frightened villagers this is-- they actually tell Renfield why his travel plans unnerve them so!), the diminutive real estate agent thinks the concern of the local rustics to be no more than obsolete superstition.

This is where Dracula makes its first mistake. Rather than follow Stoker’s lead, and only gradually reveal that everything the villagers say about their lord is true and then some, the film tips its hand early by cutting immediately to a shot of a vault beneath the castle. Apart from the cobwebs, the only thing in this vault is an assortment of coffins, all of which slowly begin to open and dislodge their occupants. (Somebody please tell me the shot of the enormously fat insect skittering out of the two-inch micro-coffin was an ill-conceived attempt at humor...) After a few moments of this, Dracula (Lugosi-- who else?) stands revealed in all his stiff-backed, awkward-gaited glory, pacing away from one of the caskets toward a stone staircase leading up out of the vault. The count is there at the pass a little while later, disguised as the coachman whom Renfield was to meet for the last leg of his trip to the castle. There’s a great moment on the ride up the final ridge, when Renfield looks out the window and sees a huge rubber bat leading the horses-- whose barding makes them look eerily like the skeletons of horses from this angle-- along the craggy mountain path. By the time the coach pulls up to Castle Dracula’s main gate, the bat is gone, but so are the driver and Renfield’s luggage. At least the gate is unlocked, but that’s not much comfort to Renfield, who now finds himself standing in an atrium hall that looks as though it has not been used since the Turkish conquest. Everything is in terrible disrepair, and it is impossible to take a step without pushing through a layer of cobwebs a quarter of an inch thick. Renfield’s in the right place though. A few seconds after coming inside, he notices a man in a black cape standing at the top of a ruined staircase. You all know the line: “I am................. Dracula... I bid you velcome.” And it’s all downhill from here for our buddy Renfield. By the end of the night, he’ll have been half vampirized, and have traded in his position with the real estate firm for a new job as the count’s private bug-eater. Worse still, he doesn’t even receive the partial compensation of having Dracula’s three hot girlfriends take turns sucking his blood like Harker nearly does in the book!

Cut to a shot of a crappy model sailing ship on a stormy sea worthy of a Daiei flick. The ship is the schooner Vesta, on which Dracula has hired passage to England. The ship reaches port despite the storm, but by then, Dracula has seen to it that none of its crewmen are alive to enjoy their homecoming. The only man left standing is Renfield, who is now obviously completely out of his mind. He ends up in the sanitarium run by Dr. Seward (Herbert Bunston of The Monkey’s Paw), which, conveniently enough, is located right across the street from Carfax Abbey, the property that Dracula has arranged to lease. All this comes out in conversation when the count drops in on Seward, Mina (Helen Chandler), Lucy (Frances Dade) and John Harker (David Manners, whom we’ll be seeing again in The Mummy and The Black Cat) at the opera (after an evening on the town drinking the blood of paupers and street vendors). And it is in this scene that Dracula figures out what he’s going to put in those other two boxes of unhallowed Transylvanian earth he brought with him from home-- they look like they’ll fit Mina and Lucy quite nicely.

In that light, it’s awfully convenient for Dracula that Lucy took quite a liking to him at the opera. She ends up the vampire’s latest victim in no time at all, opening the door to Dracula’s biggest and most inexplicable plot hole. To wit: the girl’s so-called friends scarcely seem to notice when Lucy dies! Her death is used as an excuse to introduce the character of Dr. Van Helsing (Edward Van Sloan, whom Universal would use again for similar roles in Frankenstein and The Mummy), and then forgotten about entirely for much of the film. And even after she re-enters the story as the lady in white who begins terrorizing the neighborhood kids a few scenes down the line, we only hear about her activities, and she is forgotten about again long before Van Helsing and his band of reluctant vampire-killers get a chance to stake her! Anyway, Van Helsing arrives out of nowhere with nary a hint of explanation at about the time of Lucy’s death, and we in the audience are left to extrapolate that some kind of connection exists between the disappearance of the one character and the arrival of the other. The doctor has clearly never read Dale Carnegie, because he makes his first impression proclaiming to a panel of doctors and police officials that Lucy’s death and those of the paupers who have been dropping like flies ever since the Vesta put into port are the work of a vampire. But apparently this lot is more easily convinced than you or I, because not only do they not send him packing on the next boat back to Holland, Dr. Seward actually allows him to come have a look at Mina, who has been behaving strangely ever since she had an unsettling nightmare soon after her friend’s demise.

By another stroke of serendipity, the count puts in an appearance at Seward’s place (and by the way, this is the first indication we’ve seen thus far that the two men had kept up their acquaintance since they met at the opera) just as Mina finishes telling Harker, Van Helsing, and her father about her disturbing dream. A quick look at Mina’s neck, which the girl is loath to allow, reveals that she too has been receiving visits from the vampire, and Van Helsing notices while reaching for a cigarette that Count Dracula casts no reflection in the cigarette box’s mirrored lid. After Mina has gone to bed, the doctor asks Dracula to help him confirm an observation he has just made of a “most curious phenomenon” by looking into the box. The enraged vampire slaps the box out of the man’s hand, tells him “you know much for a man who has not yet lived even a single lifetime,” and stalks out of Seward’s parlor. Van Helsing spends the next couple of scenes comparing notes with Renfield and fruitlessly trying to convince his hosts that the Count is a vampire. Mina finally ends up doing the convincing instead when she attacks John one night after that sorry-ass rubber bat buzzes the couple out on the balcony. She then reveals that she’s been seeing quite a lot of Dracula, and that the count had forced her to drink his blood on his last visit. Then, while the other characters are standing around trying to figure out how to handle the situation, Dracula abducts Mina and takes her next door to Carfax Abbey. Renfield breaks out of his cell (security must suck a big ass at Seward’s sanitarium, as he seems to do this about every hour, on the hour) and follows his master home, inadvertently leading Harker and Van Helsing to the vampire’s resting place for the extremely disappointing final showdown.

On the plus side, Dracula is a visually stunning film. If there was one thing Universal’s people understood, it was the power of light and shadow to establish a mood, especially on black and white film. The set design is excellent throughout the movie, and all the matte paintings are well integrated with the foreground action to produce believable layered images. Unfortunately, that’s about all Dracula has going for it. Karl Freund’s camera is amazingly static, and combines with Browning’s clunky direction to give the movie the feel of a stage play captured on film. The editing is unimaginative as well, and the film’s pacing suffers because of it. The script is excessively talky, yet remains damningly unclear on a number of important plot points. I’ve already mentioned the screenwriter’s curious inability to keep track of Lucy after her demise and the total lack of explicit justification for Van Helsing’s entry into the story. But there’s more, much more. After the Lucy-related troubles, the most serious flaw in the script concerns Renfield. His role in Dracula’s scheme is never explained; for all the time he spends alluding to things the count has made him do, the only function we ever see him perform is to spill his guts to Van Helsing. You might guess that Dracula needs Renfield to provide him with an agent inside the Seward household (the doctor lives on the grounds of his asylum), but that can’t be it because whenever the need comes up, the vampire merely hypnotizes one of the household servants instead. Given the amount of screen time Renfield receives (he’s on camera more than any other character), this lapse is all the more baffling.

And then there’s the acting. Such a display of hamming, woodenness, and wooden hamming is a rare sight indeed. I’m getting tired of picking on Bela Lugosi (though the guy certainly deserves to be picked on), so instead I’ll turn my attention to the supporting cast. Edward Van Sloan is especially disgraceful as Van Helsing, with his absurd phony accent, his overwrought delivery, and his tone-deaf inflection. I suppose it could be argued that he’s merely playing the role as Stoker wrote it, but even that is a pretty flimsy excuse. Stoker, for all his renown, was a hack writer with no grasp whatsoever of characterization. To act according to his writing is, on its face, a terrible idea. Dwight Frye’s much-lauded performance as Renfield is another sacred cow in search of a barbecue pit. As bad as his spasmodic mugging and face-pulling is throughout the bulk of the movie, his musty, lifeless underacting as the sane Renfield is even worse. The rest of the cast isn’t so aggressively terrible, and the stiffness of their performances can perhaps be excused by the script’s failure to give them much of anything to do, but it’s a bad sign when the most convincing performances come from the unnecessary comic relief players, in this case the asylum’s put-upon cockney orderly and his friend the cleaning lady. In short, we have in Dracula a movie whose classic status rests solely on the unsteady foundation of priority. Nevermind that it’s one of the worst; it gets to be a classic because it was one of the first. Perhaps you think I’m being unduly harsh here, judging Dracula according to an anachronistic standard that its age prevents it from measuring up to. But I am doing no such thing, for even as this movie was being shot, another cast and crew were using all the same raw materials to create something far more interesting after Browning’s people went home for the night. But that is another story, and belongs in another review...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact