Nosferatu / Nosferatu the Vampire / Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror / Nosferatu: The First Vampire / Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922) ****

Nosferatu / Nosferatu the Vampire / Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror / Nosferatu: The First Vampire / Nosferatu: Eine Symphonie des Grauens (1922) ****

Horror movies have been around since the very birth of cinema-- the earliest one known is a one-reel version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde from 1908, and many of Georges Meliesís pioneering fantasy shorts from the turn of the century include arguably horrific elements. But during the silent era, horror films were produced only sporadically throughout most of the world. This was not the case, however, in Germany. It was there that the horror film first emerged as a recognizable cinematic genre, with its own distinctive set of conventions and attributes. This is hardly surprising, because 1920ís Germany was also the birthplace of expressionist filmmaking, with its emphasis on eerie, dreamlike, disorienting imagery, an emphasis that in retrospect seems tailor-made for directors who wanted to scare the shit out of their audiences. Indeed, many of the most famous German films from this period are horror pictures: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Golem, The Hands of Orlac, and of course, F. W. Murnauís legendary Nosferatu.

This was, so far as can be definitively determined today, the worldís first movie based directly on Bram Stokerís oft-filmed Dracula (another picture, now lost, called The Death of Drakula was released in Hungary in 1921, but rather than telling anything like Stokerís story, it used the Dracula character as the centerpiece of a rather blatant Cabinet of Dr. Caligari rip-off), and in my opinion, it remains among the top echelon of Dracula flicks, even after most of 80 years. Murnau and screenwriter Henrick Galeen greatly revised the storyline when they made Nosferatu, paring down Stokerís ensemble cast of heroes and heroines and drastically shifting its emphasis to bring in an angle Stoker seems never to have considered-- the plague. In addition, they began what would develop into a full-scale tradition of reshuffling the relationships between Stokerís characters. Indeed, Galeen went so far as to change all of their names. (Most English-language prints of Nosferatu, however, use Stokerís names for the characters in the intertitles-- the exception being Mina Harker, who is called Nina. But for the purposes of this review, I will mostly be using the German names, Ďcause thatís just the kind of guy I am.) As I will explain later, Galeen had a very good reason for doing things the way he did.

Thomas Hutter/Jonathan Harker (Gustav von Wangenheim, from By Rocket to the Moon) is a real estate agent living in Wismar (Bremmen in most English-language versions). One day, his boss, Knock/Renfield (Alexander Granach) assigns him to close what promises to be an insanely lucrative deal for the agency. A Transylvanian nobleman named Count Orlock/Count Dracula (the unforgettable and aptly-named Max Schreck-- his last name means ďfrightĒ in German) wishes to lease a house in town, and Knock thinks the dilapidated old mansion across the street from Hutterís place will suit the countís peculiar tastes perfectly. As Knock tells his employee, the count is very rich and famously free with his money-- Hutterís commission, should he undertake the assignment, ought to be huge. Thatís all Hutter needs to hear. Within days, heís left his wife Ellen/Nina (The Golemís Greta Schroeder) in the care of his friends, the Westrenkas/Westenras, and set off on the long trip to Transylvania.

Once there, Hutter has difficulty in getting the country people to cooperate with him in his efforts to reach Orlockís castle. The countís peasants all seem to be afraid of him and his home for some reason that goes well beyond their professed dread of the wolves that prowl the forests surrounding the castle. (These wolves, by the way, will be played by hyenas when we see them! Your guess as to why is as good as mine.) Finally, after much wrangling, Hutter manages to get a coachman to drive him in the general direction of Orlockís place, but only so far as will allow him to be back home in the village by nightfall. Hutter doesnít understand, but heíll take what he can get.

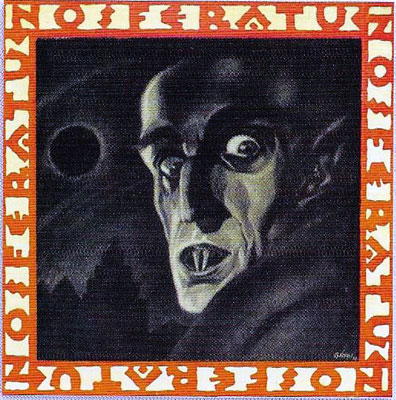

After the coachman drops Hutter off, he has only a little while to wait before a second carriage appears, richly enough appointed that it can belong only to Orlock, and traveling at impossibly high speeds. Its driver is at least as unnervingly weird as the vehicle, but Hutter climbs aboard anyway-- it beats walking, after all! At the journeyís end, Hutter is ill-prepared for the sight of the castle, though his first look at it goes some way toward explaining why its owner would want to lease the ruined mansion back in Wismar. This place is in even worse shape, looking like it was never repaired after an especially fierce siege by the sultanís armies. But for all its decrepitude, at least part of it is still habitable, and Hutterís host meets him just inside the gate. I donít care how much money was in it for me-- I would not, under any circumstances, spend the night alone with this guy. Even in washed-out, 80-year-old black and white, his skin has noticeably less color than anyone elseís, and heís got eyes like a cat, the pointed ears of a bat, a ratís elongated incisors, and dagger-sharp fingernails almost three inches long. Consider also the fact that he lives, apparently alone, in a ruined castle in a forgotten corner of the Carpathian mountains, and that all his neighbors are afraid of him, and the overall picture of Bad News emerges fairly clearly. But then again, itís not like Hutter has a hell of a lot of choice in the matter. Heís many hundreds of miles from home, heís already ascertained that no coachman in the area is willing to work at night, and he does have a job to do. So he sucks it up, and tries to retain his composure even in the face of all the doors that open and close all by themselves, all the creepy dreams he has when he tries to sleep, and all the times the count disappears, leaving him alone in the castle during the day. He even finds a way to keep from running off into the wilderness when Orlock tries to suck on his bleeding finger after he cuts himself on a bread knife at dinner one evening, and when the count later makes what looks, to 21st-century eyes at least, an awful lot like a sexual advance toward him.

But when Hutter discovers a pair of bite-marks on his neck one morning, and begins to come down with a curious wasting sickness a few days before he was to leave for home... well, thatís an altogether different story. Hutter, you see, has been reading himself to sleep at night with a book he picked up at the village inn, called The Book of the Vampire, and he has begun noticing some uncomfortable echoes of its subject matter in his own life now that he has come to Orlockís castle. Eventually, when heís had just about all the mystery he can stand, Hutter decides to have a look around the castle. His investigations uncover, in an underground vault beneath a ruined part of the building, a badly deteriorated sarcophagus. When Hutter bends over to have a look through a gaping crack in its lid, he finds himself face to face with his host, sleeping the sleep of the dead inside the decayed coffin. But Hutter was late in catching on, and he is no position to do much about it when he sees Orlock loading up a flat-bed cart with coffins full of earth that night. The vampire climbs into the last of the coffins to be stacked on the cart, and the wagon speeds off down the road toward civilization.

Meanwhile, back home, Ellen has been having a rough time of it. Ever since Hutter left, sheís been having nightmares, sleepwalking episodes, inexplicable feelings that her husband is in grave danger-- the works. If only she knew that even then, Hutter was making his sickly way across Europe, racing not only against the course of his vampire-inflicted illness, but against Count Orlockís own progress toward Wismar. Itís a good thing for Hutter that Orlock is not taking the land route, but traveling instead by ship across the Black Sea, through the Mediterranean, and around Europe the long way. At least this way, he has a chance of reaching Wismar before the vampire.

Which leads us to Orlockís voyage on the Demeter. Itís the one element of Stokerís novel that features in every film version of the story that I know of (with the sole exception, that is, of Horror of Dracula), and with good reason. In the right hands, the sea-voyage and the subsequent arrival of the ghost-ship in port can be made into a surpassingly eerie vignette. Murnau has the right hands. In fact, I think this is, bar none, the creepiest treatment this part of the story has ever received. For one thing, Murnau drags it out by having the vampire kill off the crew gradually, allowing them to believe that their ship has become infested with plague-bearing rats; in point of fact, it has, but thatís the least of the sailorsí worries. Secondly, this part of the film contains Nosferatuís most striking visual, the scene in which the Demeterís captain goes down into the hold after he and his first mate toss the body of their last sailor overboard, and encounters the vampire face to face. The captain hacks open the lid of one of Orlockís coffins with a hatchet, finding it filled to overflowing with rats. When he goes to the next coffin, however, its lid flies open of its own accord, and Count Orlock springs bolt upright from within it. The vampire kills the captain, and then climbs up to the main deck to get the first mate. When the Demeter arrives in Wismar, the first mateís body is the only sign left of the crew.

Once in town, Count Orlock unleashes an outright holocaust. His very presence in the city drives Knock mad and lowers a pall of inexplicable melancholia on Ellen that even the return of her ailing husband cannot lift. But more importantly, the vampire soon begins to depopulate Wismar, partly through his own activities, partly by means of the plague-bearing rats that he brings with him. There is only one thing that can stop him-- a woman, pure of heart, must seduce the vampire, offering her blood and keeping him by her side until morning, when the first rays of the rising sun will destroy him. And fortunately for Wismar, when Hutter came home from Transylvania, he happened to leave The Book of the Vampire lying around where his virtuous wife was sure to find it.

Nosferatu is by no means a perfect film, and is handicapped significantly by the radical differences in cinematic conventions that separate the silent era from what we are accustomed to today. Most of its performances are overplayed, in the manner of old-fashioned stage acting, which required excessively broad gesturing and exaggerated facial expressions if those in the more distant seats were to be able to tell what was happening onstage. In the context of a motion picture, in which the only audience is a camera standing a few yards away, this comes across as preposterous mugging. Secondly, it was virtually impossible to film at night in 1922, so all nighttime scenes were actually shot in broad daylight. Originally, these scenes were tinted blue in order to differentiate them from those that were supposed to take place by day, but to the best of my knowledge, only the extremely high-class German restored version features this tinting today, and any version an American is likely to find on home video will be entirely in black and white, leaving it perfectly obvious that the sun is shining during scenes that are supposed to take place in the dead of night. Finally, many of the tricks used to impart an air of supernatural menace to the vampire and his castle look more than a bit silly now. The best example of this is the use of sped-up footage for all the scenes involving Orlockís carriage and for some of those in which the vampire carries his coffin through the streets of Wismar.

On the other hand, those facets of Nosferatu that do still work are simply incredible, especially in the context of its time. Indeed, on closer examination, Nosferatu is an astoundingly modern movie. A tremendous amount of the filmís footage was shot outdoors, on location, an extraordinary hardship in the days when movie cameras were balky, hand-cranked machines prone to frequent, debilitating breakdowns. Murnauís camera is also extremely mobile, changing angles far more often than was common in the silent era. This ends up being a very important asset, because with a more static directorial approach, the filmís brooding pace would become too much to bear, and Nosferatu would simply collapse under its own weight. The frequent changes of shot thus make possible the somber, oppressive, nightmarish feel that is the movieís most striking characteristic. The practiced eye notes, too, that Murnau was not afraid to employ explicit horrific imagery, at least by the standards of his day. A comparison with Tod Browningís Dracula is especially instructive in this respect. Dracula is too squeamish even to show the count emerging from his coffin; one of Nosferatuís most powerful images depicts just that. In Dracula, when the port authorities board the Vesta and find its crew dead, the camera shows us the shadow of the first mateís lifeless hand hanging from the helm; the camera looks the Demeterís dead first mate square in the face in Nosferatuís corresponding scene. But most importantly, there is the character design of the vampire himself. Lugosiís Dracula is an Old-World gentleman with some strange and off-putting mannerisms. Schreckís Count Orlock is a horrific ghoul, his visage grandly evocative of the timeless evil that was the vampire of medieval folklore. Finally, pay close attention to Nosferatuís final scene. Even today, Hollywood wouldnít touch that ending with a ten-foot pole.

Today, there are several versions of this movie available. The most common appeared on video in the late 1980ís, and is made from a fairly battered print of the American-release version. There are also a couple of restored versions out there, with superior picture quality, newly-translated intertitles closer to the spirit of the German originals, and as much of the original score as could be reconstructed. At least one German-language edition restores the blue tint to the nighttime scenes. The only version out there that Iíd advise people to steer clear of is the one called Nosferatu: The First Vampire, which tastelessly replaces the various orchestral and organ scores with which the film has circulated with a new soundtrack by meathead goth-rockers Type O-Negative. Call me a snob if you want, but I think thatís incredibly crass, and indeed outright disrespectful.

But whatever personal feelings I or anyone else might have regarding the merits of this or that version of the film, the very fact that we have a choice is a remarkable and recent development. For a long time, Nosferatu was a difficult movie to find. Small wonder, that. Indeed, we are incredibly fucking lucky to be able to see this movie at all! You see, Florence Stoker, Bramís widow, was still alive in 1922, and the great bulk of her income came from Draculaís royalties. She thus understandably kept a watchful eye on all Dracula-related activity around the world to make sure she received every penny to which she was entitled. For reasons that have never been satisfactorily explained to me, producer Albin Grau never bothered to get Mrs. Stokerís permission before he set about making Nosferatu. Thatís why all the characters were given new names in the original German version, and it probably also had something to do with such changes as the elimination of Arthur Holmwood, Quincy Morris, and Dr. Seward, and the reduction to the point of irrelevancy of Lucy Westenra and Dr. Van Helsing (Called Professor Bulwer in the German version, and played by John Gottowt, from The Hunchback and the Dancer and The Student of Prague). Enough was left of the original story, though, for the jealous Mrs. Stoker to spot the movieís basis in her husbandís novel, and she immediately sued for copyright infringement. It would appear that German law in those days provided for rather more vigorous copyright protection than American law does today, because the court that heard the case found in favor of Mrs. Stoker, and ordered all copies of Nosferatu destroyed, along with the negatives. The most fascinating thing about this odd tale is that Grau clearly realized he was violating Stokerís copyright, and that dire consequences would result if Florence Stoker ever found out. Why, then, did he do it? If anyone knows, they havenít told me. Weíd just better be thankful the German authorities missed a few copies when they went about consigning Nosferatu to the flames.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact