The Hands of Orlac / Orlacs Hände (1924/1928) ***

The Hands of Orlac / Orlacs Hände (1924/1928) ***

If you’re a lifelong fan of horror movies, and any significant fraction of your childhood fell between the early 1970’s and the mid-1980’s, then there’s an excellent chance that you spent a lot of time poring over the tantalizing text and imagery of Denis Gifford’s A Pictorial History of Horror Movies. You might not remember it by name (I didn’t until I stumbled upon a copy in a used bookstore in Baltimore in the summer of 2003), but it was ubiquitous in the film sections of public libraries in those days, and together with the more narrowly focused Monster Series published by Crestwood, Gifford’s tome did for my generation of horror nuts what the Warren Group’s Famous Monsters of Filmland did for our parents. I bring this up because it was in the pages of A Pictorial History of Horror Movies that I first encountered a film that would beckon to me across the ages for some 25 years— Robert Wiene’s The Hands of Orlac.

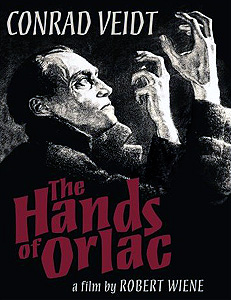

Part of The Hands of Orlac’s allure for the eight-year-old El Santo was simply a matter of the title, with its strong (if probably also coincidental) phonetic echo of the villain from the comparably ancient and even more enticing Nosferatu. But mostly it was the exquisitely ghoulish notion of a man whose transplanted hands may be driving him to kill— and if the prodigious number of remakes and rip-offs this movie spawned is any indication, I was by no means alone in recognizing the appeal of that premise. Having now seen it, I suppose I have to admit that The Hands of Orlac didn’t quite live up to the fevered anticipation of a quarter-century. Like Mad Love, the more accessible American remake from 1935, the original film is undercut to some extent by a most un-Germanic “rational explanation” ending that backs timidly away from the most horrid implications of what we have seen up to then, but it compensates for that weakness with loads of oppressive atmosphere and a tortured performance from Conrad Veidt that the later version’s Colin Clive never comes within shouting distance of matching.

Veidt (seen later in The Thief of Bagdad and F.P. 1 Doesn’t Answer) plays internationally renowned pianist Paul Orlac, who, when we meet him, is just wrapping up his latest tour, his mind focused almost completely upon the longed-for reunion with his wife, Ivana (Alexandra Sorina). It will not happen precisely as either one of the Orlacs expects. On the outskirts of Paris, there is a malfunction with one of the railroad switches, and Orlac’s train derails. Ivana rushes out to the site of the wreck as soon as she hears the news, eventually finding Paul herself amid the twisted ruin of the train. He’s alive, but very badly hurt. Fortunately, there is a doctor whose clinic stands very near to the Orlac house, and Ivana arranges to have Paul taken to him. Dr. Vinberg’s prognosis is decidedly mixed. Paul will live and indeed recover, broadly speaking, but his hands were severed in the crash, and there is simply nothing that Vinberg can do about that. This is appalling news, for one can hardly carry on a career as a piano player without any hands! Vinberg is moved by Ivana’s histrionics, but it isn’t until he glances out the window, and sees the hearse hauling away one of the patients he was not able to save, that an unusual idea occurs to him. The doctor cryptically tells Mrs. Orlac that there may be something he can do for Paul after all, and then retreats into his operating theater, leaving Ivana to rest in the office.

Vinberg’s brainstorm, of course, was to transplant the hands of a dead man onto Orlac’s stumps. Specifically, the hands come from a recently executed serial killer named Vassar— although actually telling Orlac that once his recovery is well underway probably isn’t the smartest thing the doctor could have done. Orlac seems pretty high-strung to begin with, and you can imagine the sort of fanciful worries that begin weighing on his mind once he finds out that his grafted appendages had been used by their previous owner to toss knives into people. Orlac doesn’t just start getting the wiggins whenever he picks up anything sharp, either. He also begins seeing a squinty-eyed bald man (Fritz Kortner, of Warning Shadows) watching him from odd places around Vinberg’s clinic during his initial convalescence, and what’s worse, a note asserting ownership of Orlac’s new hands is there to greet Paul in his bed when he awakens from a nightmare about the mysterious stranger. By the time the doctor decides it’s okay to release him, Orlac is just about ready for a different sort of in-patient therapy.

Paul’s strange experiences at the clinic appear in a new light when a man calling himself Nero accosts Regine, the Orlacs’ maid (Carmen Cartellieri, from Parema, Creature of the Star World), outside of the house and strong-arms her into “going into business” with him. That’s right— Nero’s the squinty-eyed guy from Vinberg’s place! The precise form of cooperation that Nero wants from Regine doesn’t sound like much to exchange for staying alive. All he asks is that the maid introduce the subject of Orlac’s hands into conversation as often as possible, and keep her mouth decorously shut on the subject of Nero himself.

Not surprisingly, Paul’s emotional state doesn’t improve much after his release from the clinic. He continues to have troubling dreams, begins having sleepwalking episodes, develops odd new nervous habits relating to his hands, and even discovers that his handwriting has become unrecognizable. Naturally, he attributes all of these things to the influence of some piece of Vassar’s spirit that remained within the hands when they were sawn from the killer’s corpse. And if that were true, then mightn’t it mean that the dead man’s hands could one day induce Orlac to take up the bloody work to which they had so often been put? Ivana and Vinberg both tell him that such notions are absurd, but Paul can’t seem to make himself believe them.

Now while I’m sure it would be awfully trying to have to entertain fears that your hands wanted to turn you into a murderer, Orlac has a more pressing problem before him, in that Vassar’s fingers don’t possess anything like his old dexterity. Paul is going to have to re-acquire his musical skills essentially from scratch, a daunting prospect on a number of levels. He and Ivana have plenty of money in the bank, at least, but the lifestyle to which they are accustomed entails spending plenty of money, too. With their income standing at around zero until Paul is able to play the piano again, that places a lot of pressure on a mind that is ill-equipped to handle it. The more Orlac agonizes over his mounting financial woes, the more frustrated he becomes with his inability to play, and the more the pace of his recovery slows. Eventually, the household savings run out, and Ivana concludes that there is nothing to be done but to approach her father-in-law about a loan. That decision comes with its own baggage, for Old Man Orlac (Fritz Strassny) hates his son, and disowned him many years ago. Ivana’s appeal to him meets with no success, but she thinks maybe Paul himself might have more luck.

Paul, as it happens, is indeed going to be receiving money from his dad, but not at all in the way Ivana imagines. When he arrives at his father’s gloomy, German Expressionist mansion, he finds that somebody got there before him, and murdered the old man with a knife in the back. Orlac summons the police, but the presiding detective’s initial examination reveals two startling, and seemingly impossible, facts. First, the knife with which Orlac Senior was stabbed to death was part of a set that Vassar used to dispatch all of his victims. And secondly, Vassar’s fingerprints are all over the crime scene. The inspector may not know what to make of that information, but Orlac sure thinks he does. After all, he’s been sleepwalking of late, and all his life, he’s hated his father nearly as much as his father hated him. Furthermore, the old man was disgustingly rich, and had no living relatives other than his estranged son, making his death extremely convenient for Orlac right about now. What if Paul, during one of his sleepwalking episodes, and guided by the latent memories of his secondhand hands, reclaimed one of Vassar’s favored weapons, and committed patricide?

Of course, we in the audience already know that he did no such thing— otherwise, how to explain Nero’s shady behavior?— and this foreknowledge is both a great detriment to The Hands of Orlac and a point of superiority for it over the American remake. On the one hand, having a rational explanation for seemingly supernatural (or at least paranormal) events is almost always a terrible bore, and by 1924, the German film industry had about a ten-year tradition of being practically the only one in the world that consistently showed little patience with such lily-livered back-pedaling. But then again, having it made plain up front that the “evil hand” business is all in Orlac’s mind means that the cop-out doesn’t show up out of nowhere like a gaudily gift-wrapped turd in the final scene of the film, as happened in so many other early horror movies. Indeed, even when Nero meets with Orlac, posing as Vassar with a brace around his supposedly guillotined neck and a pair of steel gauntlets “replacing” his supposedly severed hands, the story he tells about how Vinberg reanimated him as part of some mad experiment rings so false that we know automatically that it has been concocted in order to push Paul all the way over the edge. Compare this scene to its counterpart in Mad Love. There, when Dr. Gogol removes his disguise after Orlac has gone home, it becomes a major letdown, because we’ve already seen Gogol’s mad-scientist credentials, and they are impeccable. Gogol, unlike Vinberg, surely would be capable of doing what “Rollo” (as the Vassar character was called in the remake) claims he has done, and it is extremely irritating to discover that he has not. In The Hands of Orlac, the mystery is not whether Orlac is being taken over by the spirit of a dead murderer’s hands, but rather why Nero wants him to believe he is. The rational explanation is still a frustration, but at least it isn’t a cheat (except, of course, in the details of Nero’s scheme, on which even a perceptive child is likely to call bullshit).

The other main points in the original version’s favor concern Conrad Veidt’s performance and the handling of the train wreck that sets the story in motion. Together with Paul Wegener, Veidt was among the very first screen actors to become recognized primarily for their work in horror films. After his breakthrough role as the deadly somnambulist in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Veidt played Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (or rather, “Dr. Warren” and “Mr. O’Connor”) in The Janus Head, an animated likeness of Ivan the Terrible in Waxworks, and even the Devil himself in Satanas, F. W. Murnau’s ponderous epic of evil throughout history. Hollywood got the hint, too, importing Veidt for The Man Who Laughs in 1928, and keeping him busy (apart from a few years’ interlude in the early 30’s) with exotically villainous parts up until his premature death in 1943— indeed, Veidt had been among the front-runners to step into the title role when Lon Chaney’s similarly premature demise left Dracula high and dry without a vampire. Veidt was an interesting choice for the part, not of a killer, but of a man who believes himself to be a killer, and while his performance here is somewhat overwrought, it is overwrought in a way that dovetails with the emotional torment that Orlac experiences throughout the film. It’s the sort of portrayal Klaus Kinski might have given 50 years later. As for the crash that divests Orlac of his hands, it is there, I think, that we see most clearly the oft-noted influence of World War I upon German horror in the 1920’s. Mad Love doesn’t spend much time on the derailment, preferring instead to get on with the mad science. The Hands of Orlac, in contrast, treats it as a major (albeit subtly orchestrated) horror set-piece in its own right. The set-dressers rendered the crumpled wreckage of the train in loving detail, and director Robert Wiene staged and recorded the hectic efforts of the rescue crew to herd the survivors to safety and to recover the dead and wounded as if he had seen very much the same thing any number of times in real life— which indeed he may have if he, like so many of his contemporaries, served a stint in the Kaiser’s army. It’s almost as if, with this scene, Wiene is saying, “Listen, I know you’re all here to see Conrad get a murderer’s hands grafted onto his wrists, but first I want to show you something. Look at this. This is horror, people— 1000 bleeding bodies in a heap of mangled steel. And it’s also how most of the men in my generation spent four years of their lives, do you understand?” The desensitized, documentary sensibility that animates the crash scene gives it far more impact than even the most effective of the fantastical horrors that follow.

Thanks to Liz Kingsley for furnishing me with a copy of this film.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact