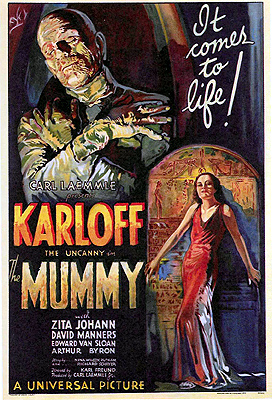

The Mummy (1932) **

The Mummy (1932) **

It isn’t a point that’s brought up very often, but most of the very oldest American horror movies had a literary or dramatic basis. Everyone knows the origins of Dracula and Frankenstein, but those are only the most obvious examples. Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, The Cat and the Canary, The Lost World, The Phantom of the Opera-- all were based on well-known stage plays or novels of more or less classic stature. In fact, the only American horror film from this very early period that I can think of off the top of my head which was not based on some novel or play is the long-lost silent vampire flick London After Midnight. But suddenly, in 1932, American filmmakers began turning out horror movies whose screenplays were original stories in and of themselves. The Mummy was among the first of these films. It was also possibly the very first US horror movie designed to cash in on a cultural fad from the world beyond Hollywood-- in this case, the lingering afterglow of the Egypt-mania that swept the Western world in the wake of the 1922 discovery of King Tutankamen’s undisturbed tomb.

You may recall that some of the men who excavated that ancient grave died soon thereafter under mysterious circumstances, giving rise to rumors of a generic “Pharaoh’s curse” lingering over all the burial grounds of ancient Egypt. The Mummy’s script milks this sensational episode for all it’s worth, beginning with the discovery of another untouched tomb by an Egyptologist named Dr. Joseph Whemple (Arthur Byron). Whemple has found the grave of Imhotep, a member of the priestly class who lived more than 3700 years ago. And if the state of his grave-goods is any indication, he did not die a popular man. To begin with, his coffin was vandalized before the tomb was sealed, the hieroglyphs spelling out the incantations ensuring safe passage to the afterlife chiseled away. Not only that, a cursory examination of the mummy by Whemple’s colleague, Dr. Müller (Edward Van Sloan, of Dracula and Dracula’s Daughter), turns up evidence that Imhotep was interred alive. But the most interesting thing in the old tomb is a badly decayed cedar chest housing a large gold-plated coffer. The coffer’s lid is inscribed with a curse, condemning anyone who opens it to madness and death, and Müller is adamant that Whemple heed the ancient warning, and bury the chest back in the sand where he found it. The old scientist, like his younger and more skeptical colleague, believes the coffer contains the legendary Scroll of Thoth, on which was written the text of the spell that Isis used to raise Osiris from the dead. Müller takes Egyptian magic very seriously, and he fully believes not only in the power of the curse, but also in that of Isis’s spell, a power which falls smack in the middle of the category “Things Which Man Was Not Meant to Know.” It’s really a moot point, though; while Müller and Whemple argue out in front of Whemple’s headquarters in the field, the archaeologist’s young assistant impetuously opens up the cursed coffer, removes the Scroll of Thoth, and begins transcribing it, muttering its words aloud as he does so. This has the not-unpredictable effect of bringing Imhotep’s mummy to life, and the crispy old priest immediately relieves the apprentice Egyptologist of both the scroll and his sanity, and then shambles off into the night, somehow avoiding the attention of the two older scholars.

Ten years later, Whemple’s son Frank (David Manners, from Dracula and The Black Cat) is following in his father’s footsteps. Or at any rate, he’d like to be. As a matter of fact, the younger Whemple is not nearly so successful an Egyptologist as his old man, and a couple of dusty potsherds are all he has to show for an entire season of fieldwork. All that changes, though, when a man named Ardath Bey (Boris Karloff) walks into Frank’s camp with a very promising artifact. The stranger is something of an amateur Egyptologist himself, and though the customs of his land forbid him to disturb the ancient tombs, he is not above pointing a few white guys from England in the right direction now and then. This time, Ardath Bey thinks he’s found a clue to the whereabouts of the lost grave of the princess Ankh-es-en-Amon. The artifact he presents to Whemple was lying half-buried in the sand not 100 yards from the site of his thus far miserably unproductive excavation, and yes indeed, Ankh-es-en-Amon’s grave is concealed about eight feet underground in that very spot. This is one hot-shit tomb-- the thing has never been opened before, not even by grave-robbers. The princess’s mummy is there, and so are thousands of pounds’ worth of ancient treasures. Looks like Ardath Bey has made Frank Whemple one famous motherfucker.

The treasure of Ankh-es-en-Amon makes quite a splash when it is debuted at the Cairo museum some time later. Indeed, it’s even enough to lure the elder Dr. Whemple back to Egypt, where he has not set foot since the day the resurrected Imhotep walked off with the Scroll of Thoth. At the museum, Joseph Whemple meets Ardath Bey, and invites him over for dinner some night soon. The Egyptian declines, however, pleading an impossibly busy schedule. Perhaps he too plans to spend his time studying the newly unearthed artifacts in the museum’s collection, but somehow, it doesn’t seem very likely. This guy is just too weird to be up to anything but trouble, what with his stiff walk and his dusty voice and his great dislike of being touched. So when he sticks around after closing time in the room containing the princess’s mummy, we have some inkling of what might be about to happen. Sure enough, Ardath Bey kneels down before the sarcophagus, lights a scented candle, and unrolls-- that’s right-- the Scroll of Thoth! He’s forced to stop his conjuring in mid-stream, however, when a museum security guard spots him by the coffin. Ardath Bey kills the guard, but then flees, apparently concerned that there may be more where he came from, and in his haste, he leaves the scroll on the museum floor.

But elsewhere, as Ardath Bey intoned the spell of Isis under his breath, a very strange feeling came over a young woman named Helen Grosvenor (Zita Johann, who would show up many years later in Raiders of the Living Dead), a relative of Dr. Müller’s who was just then amusing herself at a party in uptown Cairo. Helen, who we had just learned to be half Egyptian from the conversation of two otherwise insignificant characters, entered a kind of trance state, left the party, and took a cab to the Cairo museum. She was pounding on the locked front door attempting to gain entry when the Doctors Whemple were preparing to leave for the night, and when Frank asked her why she was so hot to get into the museum, she passed out in his arms. This was about the same time that Ardath Bey was interrupted by the guard.

Helen comes to a bit later in Whemple’s study. Müller stops by to collect her, and he becomes most agitated when his old friend tells him of the circumstances under which the girl was found. The old man becomes even more agitated when he hears that the Scroll of Thoth just turned up, without a hint of explanation, in the museum beside the body of a dead security guard. Müller, who has believed for all this time that the living mummy of Imhotep was at large somewhere in the world with the Scroll of Thoth, immediately suspects that Helen has somehow come under the undead priest’s power. And while Müller and the Whemples argue the point in the study, just guess who drops by for a visit, and ends up spending a just-short-of-intimate moment with Helen. You got it-- it’s our old buddy Ardath Bey, who now that you mention it does look just the slightest bit like the mummified Imhotep we saw in the first scene. The three scientists are horrified when they come back into the parlor and find Helen making time with a 3700-year-old magician, and Müller immediately shoos the girl off to her hotel room. Then the men turn their attention to Ardath Bey, making sure he realizes they’re onto him. They know he’s really Imhotep, they know he’s trying to work some old black magic on Helen, and they know he’s the one who killed the security guard at the museum. And Imhotep, for his part, knows that Joseph Whemple now has the Scroll of Thoth, and he would very much like to have it returned to him. Müller and the Whemples stall him for a bit with denials, but it’s pretty clear they’re going to have to do better than that in the long run if they want to save Helen from whatever it is that Imhotep plans to do with her. The only way to do it, or so Müller says, is to burn the scroll, but Imhotep magically smites the elder Whemple with a stroke the moment he tries to do just that. The living mummy then has Whemple’s household servant (Noble Johnson, from The Thief of Bagdad and The Ghost Breakers), who unfortunately for Whemple is of Nubian descent (the Nubians and the Egyptians went way back, you know), throw some old newspapers on the fire in the scroll’s stead (to throw Frank and Müller off the scent) and deliver the actual article to Imhotep.

And now, at last, we get some real answers to the questions The Mummy has been stockpiling since the very first scene. Imhotep again places Helen under his power, and brings her to his curiously luxurious Cairo flat. There, he explains that Helen is the reincarnation of Princess Ankh-es-en-Amon, with whom Imhotep shared a forbidden love when he was alive the first time. Indeed, it was this love that got Imhotep into trouble in the first place; when the princess succumbed to some unspecified ailment, Imhotep stole the Scroll of Thoth from its place under the altar of Amon in the temple at Karnack, and tried to use it to restore Ankh-es-en-Amon to life. He was caught red-handed, and sentenced to be buried alive for his blasphemy, the scroll buried with him in order to prevent such a crime from ever being committed again. Now, Imhotep wants to use the scroll to transform Helen back into Ankh-es-en-Amon, whom he will then make immortal in the same way that he was. It goes without saying that Frank, Müller, and Helen don’t think that’s such a good idea.

There are two unfortunate problems besetting The Mummy. The first and most conspicuous, but frankly the less serious, of these is the fact that the film features scarcely any mummy at all. You may have noticed that practically every single book on the subject of horror movies that contains a photo of Karloff in his mummy makeup uses exactly the same image. This is because that very impressive special effect is onscreen for maybe two minutes, in five- to 30-second shots scattered throughout the first scene. For the rest of the film, his makeup is limited to a few extra wrinkles around his mouth and eyes, along with something to make his skin look unusually dry and flaky. This is a bit disappointing, but it isn’t nearly as damaging to the film as a whole as the fact that the movie’s script is basically just a rehash of the screenplay from Tod Browning’s Dracula, dressed in Egyptian drag and tarted up with a love-from-beyond-the-grave motivation for the undead villain. And the passage of time has rendered the latter point of contrast between this story and Dracula’s all but invisible, as one Dracula remake after another has adopted the very same idea. The casting of Edward Van Sloan as The Mummy’s Van Helsing figure, and of David Manners in a role very similar to that of Dracula’s John Harker, only serves to emphasize the point. I find it most instructive that this, one of the first American horror films to be shot from an original screenplay, should have so much of its story cannibalized from a film made only a year earlier-- it really says something about what “originality” means in Hollywood, if you follow me. But there is one unexpected twist in The Mummy’s reworking of the story: Note how active a role the film’s female lead plays in Imhotep’s final destruction. Whatever the movie’s faults, that’s got to be worth something, especially coming from a flick made in 1932.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact