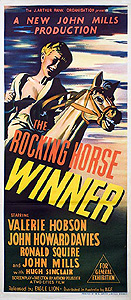

The Rocking Horse Winner (1949/1950) ***

The Rocking Horse Winner (1949/1950) ***

D. H. Lawrence is not a name one conventionally associates with horror fiction, but he does have one fairly effective tale of the uncanny to his credit. Somewhere between the dark magic realism of the more laid-back “Twilight Zone” episodes and the subjective psychological horror of Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s “The Yellow Wallpaper,” “The Rocking Horse Winner” will come as a surprise to readers who know Lawrence only for Lady Chatterly’s Lover. Understandably, given the British Board of Film Censors’ longstanding anti-fantasy prejudices, the film version emphasizes the psych-horror aspect over the paranormal, and it subordinates both to a neo-Dickensian focus on rich people behaving badly toward children. (Surely it is no coincidence that most of the principal cast had recently appeared in screen adaptations of Great Expectations and Oliver Twist.) Nevertheless, enough of the story’s eeriness remains to place The Rocking Horse Winner on the margins of Great Britain’s uncharacteristic late-40’s horror eruption, much as The Clairvoyant sat off to the side from the horror pictures being imported from America in its day.

Foremost among the children toward whom adults in this movie will behave badly is Paul Grahame (John Howard Davies). Now Paul isn’t starving to death in an evil orphanage or being set up for emotional destruction by a sadistic old lady seeking revenge by proxy on the cad who abandoned her at the altar decades and decades previously— in fact, from outside their lives, it looks like he and his two little sisters have it pretty good. They live in an enormous, beautifully furnished house; they’re doted on by both their nanny (Susan Richards, from I Don’t Want to Be Born and Village of the Damned) and Bassett the handyman (The Quatermass Conclusion’s John Mills); and their parents and Uncle Oscar (Ronald Squire, of Footsteps in the Fog) are generous and even affectionate by the reserved standards of the upper class. The trouble is, Paul’s father (Hugh Sinclair) likes to gamble, but he’s no damn good at it. Mom (Valerie Hobson, from Life Returns and The Mystery of Edwin Drood), meanwhile, likes to shop, and she’s extremely good at that. Add in the overhead on the mansion and the salaries for Nanny and Bassett, and the balance sheet for the Grahame household is chronically and pretty massively out of whack even before Dad loses his job and his poker buddies come looking for their money. Oscar— as he has apparently done on many a previous occasion— agrees to put up sufficient cash to cover the most urgent debts, but he makes it perfectly clear both that this is a loan rather than a gift, and that he is getting very fucking tired of extending such generosities. What this has to do with Paul is that his elders are less secretive than they believe about the family’s money troubles. The boy may not understand all— or even all that many— of the details, but he can’t help but notice that his mother and father are worried all the time, and that want of money is somehow at the root of it. Paul also picks up on his mother’s brooding fixation upon luck, which she conceptualizes mostly in financial terms: luck is what enables one to acquire money, so that a lucky person can always obtain cash when needed. It’s enough to give a kid a complex.

So, then— on the one hand, Paul is developing an obsession with money, and on the other, he’s developing an obsession with luck. Where on the graph, as Extension Ro-Man XJ-12 might ask, do money and luck meet? Here the always well-intentioned Bassett paves his little stretch of the road to hell by mentioning the financial side of his interest in horse racing. Bassett had been a jockey in his youth, while Paul partakes of that inexplicable love for horses that seems to be nigh universal among Europeans of his social caste, so it’s only natural that the subject of what the handyman does down at the racetrack these days should come up in conversation eventually. As soon as Paul grasps the mechanics of betting on the horses, he digs five shillings out of his coin box and implores Bassett to put it on a horse he fancies for some inscrutable, childish reason. Paul loses that time, but to Bassett’s dismay, the boy doesn’t let that deter him. Begging a loan from Oscar (who, ironically, had just finished telling his sister that she was getting no more money out of him) on the theory that he’s the lucky member of the family, Paul has Bassett put the whole of it on a horse called Daffodil at the next race he attends. Perhaps Paul is right about Oscar’s luck, too, for this second wager pays off handsomely.

This is where things start to turn weird. Paul’s parents gave him a rocking horse last Christmas, at which point Bassett admonished him that the wooden animal could take him anywhere he wanted to go if he treated it right. Seeking some means of controlling the luck he thinks he borrowed along with Uncle Oscar’s pound note, and taking an oddly literal interpretation of the handyman’s Christmas-morning advice, Paul discovers that by riding his toy horse in a frenzy of activity and concentration, he can force himself into a trance state from which he can descry the names of living horses that are destined to win upcoming races. He then passes these paranormal inside tips along to Bassett, who places the pair’s bets according to the degree of certainty that Paul evinces upon emerging from his trances. The trick doesn’t always work, and Paul conceals the means whereby he acquires his uncanny knowledge even from Bassett, but the system is successful enough to compound that initial one-pound loan from Oscar 1200-fold by the time the old man discovers his nephew’s new hobby. Oscar thinks the boy is playing pretend at first, but there’s no gainsaying the mountain of cash that Bassett produces for Oscar’s inspection when so directed by his young partner. Indeed, Oscar soon finds himself wanting in on the deal, too.

Obviously a child has little practical need for a nest-egg of that magnitude, but Paul never meant to keep his winnings for himself. All along, his intention has been to donate his racing windfall to his continually cash-strapped parents, and after a win against extraordinarily long odds balloons Paul’s betting purse to more than £10,000, he prevails upon Oscar to hand over half of the funds to his mother. To keep Mom from learning the money’s true origin (which she surely would not be pleased to hear), Oscar filters it through the Grahame family attorney with a cover story about a bogus inheritance and a trust fund configured to disburse it in £1000 increments each year upon her birthday. But if Paul was hoping to bring his mother peace of mind, he’s picked exactly the wrong strategy. Mom becomes more profligate than ever, accumulating new debts at a catastrophic rate, and driving Paul ever deeper into his vicarious neurosis with her commensurately escalating fretfulness. The more money she wastes, the more Paul feels compelled to support her. And the more pressure he puts on himself to do so, the less reliable his trance-borne racetrack prophecies become. By the time Mom and Dad notice his sorry state of neurological health, the damage may well be irrevocably done.

The Rocking Horse Winner is a real oddity, an allegorical story of subtle psychological horror told from the perspective of a child, but designed to attack the phobic pressure points of parents instead. It is less a parable of child abuse— or even child neglect, although there are certainly elements of that— than of the pernicious echo-chamber effect that a parent’s fears and obsessions can create in a child’s mind. Because Paul’s descent into self-destructive madness proceeds as much from his own personality as from his folks’ behavior, this movie posits a situation that reflects the powerlessness of childhood back onto the adults who raise him. We may recognize the Grahames’ self-absorption and irresponsibility, and we may justly peg them as bad parents because of it. But Uncle Oscar’s earnest and more or less clear-headed efforts to solve the family’s problems play a part in Paul’s dissolution, too— as, for that matter, does Bassett’s totally innocuous bit of make-believe about the rocking horse. For anyone who thinks consciously and seriously about the obligations of parenthood, this is disturbing stuff, especially because The Rocking Horse Winner carefully leaves open the possibility that the horse itself is perfectly ordinary, and the clairvoyance it imparts to Paul nothing more than a confection of happenstance and wishful thinking.

Nevertheless, director Anthony Pellissier undeniably does a masterful job of investing the titular toy with an air of ineffable menace. From the moment we first see it standing, mummified in gift wrapping, beside the Christmas tree a few hours before dawn, Paul’s rocking horse seems somehow malign and unwholesome. To begin with, this is not at all the crudely stylized slab of approximately horse-shaped planking that I imagined the first time I read D. H. Lawrence’s story. As I probably should have expected given the amount of money the Grahames throw around, the horse as depicted in this film would be a credit to any fairground carousel. As such, it occupies what Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori dubbed the “uncanny valley,” the perceptual zone in which artificial representations of living things are just realistic enough to make their shortfalls from reality unsettling. And with its perpetually gaping mouth and eyes painted in mid-roll, the wooden horse appears permanently frozen in an ecstasy of fury or terror. I would not have wanted the thing anywhere near me after bedtime when I was a kid. All Pellissier has to do to make the horse look actively evil is to fiddle with the lighting and camera angles, and he clearly knows it. Put John Howard Davies in the saddle portraying one of Paul’s frenetic trances, and you’ve got something really eerie.

Davies, unfortunately, is also the most serious drag on The Rocking Horse Winner whenever he’s doing anything other than riding his toy horse in an altered state of consciousness. By the standards prevailing among juvenile actors, he isn’t all that bad, but a little of him goes a long way. In a movie that gives us a lot of him instead, that’s a real problem. At his worst, Davies, puts me in mind of a British, blond Will Wheaton, and anyone who remembers the first two seasons of “Star Trek: The Next Generation” will understand at once what an undesirable association that can be. It’s just a good thing that he spends a relatively small fraction of his screen time in that particular red zone.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact