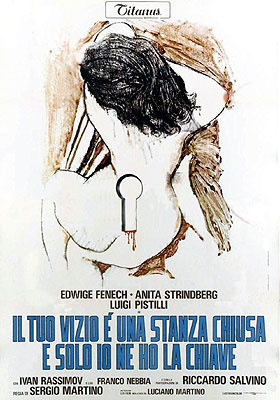

Gently Before She Dies / Your Vice Is a Locked Room, and Only I Have the Key / Eye of the Black Cat / Excite Me / Il Tuo Vizio č una Stanza Chiusa e Solo Io ne Ho la Chiave (1972) ***˝

Gently Before She Dies / Your Vice Is a Locked Room, and Only I Have the Key / Eye of the Black Cat / Excite Me / Il Tuo Vizio č una Stanza Chiusa e Solo Io ne Ho la Chiave (1972) ***˝

For such a tight, efficient, straightforward little tale, Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Black Cat” has spawned some truly gonzo “adaptations” over the years. Even the segment in Weird Tales, the oldest and most faithful film version I’ve seen, bends the plot a bit out of shape to fit the movie’s recurring theme of love triangles from hell, and things only seem to get weirder from there. Richard Matheson and Roger Corman hybridized “The Black Cat” with “The Cask of Amontillado,” and treated the resulting confection as a dark comedy. Dwain Esper hedged Poe all around with mad science and even madder medicine-show exploitation. And Universal, as was their wont in those days, chucked the source story straight into the trashcan, and just kept the title— twice! My new favorite deformation of the original tale, though, is the one inflicted on it by Sergio Martino and the usual Italian regiment of screenwriters in Gently Before She Dies. In this version, there’s a great deal more to the put-upon wife than meets the eye, and it isn’t her walled up in the cellar at the end when the cat of Poe’s title spoils the perfect crime.

Oliviero Rouvigny (Luigi Pistilli, of A White Dress for Mariale and The Eerie Midnight Horror Show) never really made it as a writer, although he’s also never really been able to admit that to himself. Fortunately for him, his dead mother, Esther, left him a big parcel of land, an impressive chateau, and enough money that his failure in his chosen profession hasn’t forced him to do anything as drastic as, say, getting a job. Still, someone who knows what to look for will recognize at once that Rouvigny is conservatively spending down inherited wealth rather than accumulating more of his own. The house is visibly decaying from lack of upkeep, and in place of the staff of specialized servants that usually go along with such a place, Oliviero and his wife, Irina (Anita Strindberg, from Who Saw Her Die? and A Lizard in a Woman’s Skin) employ only a single maid-of-all-work by the name of Brenda (Angela La Vorgna, of Rapt in Love and Emanuelle and Joanne). The one area in which Rouvigny spends his money freely is entertainment— but instead of holding balls, banquets, and masquerades for his fellow aristocrats, Oliviero prefers to have all the local counterculture types over for rock-and-roll dope orgies. They’re more fun, they make it easier for him to forget for a while about his graying hair and deepening wrinkles, and some of those hippy girls are so serious about that “free love” thing that they’ll even fuck a guy who was born the same year as the Great Depression. Indeed, there’s one such girl— Fausta (Daniela Giordano, from Inquisition and Reflections in Black), she’s called— with whom Oliviero has managed to launch an ongoing affair. Naturally, Irina isn’t happy about any of that, but the fact is, her husband’s infidelities are the least of her worries. A lifetime of frustration and disappointment has left Rouvigny meaner than a yellowjacket with a toothache, so that Irina’s marriage has become a thing of nearly unremitting abuse— physical, sexual, and psychological. And don’t even get her started on Oliviero’s weird psychosexual obsession with his dead mom, or her outsized fear of his pet black cat, Satan, which, to be fair, is almost as nasty as he is.

Then one night, Fausta is murdered by a Black Glover. Bartello (Marco Mariani, from Death Smiles on a Murderer and What Have You Done to Solange?), who owns the bookstore where the girl worked, points the police in Rouvigny’s direction, apparently knowing a thing or two not only about Fausta’s sex life, but about Oliviero’s casual brutality toward his wife as well. The inspector handling the case (Franco Nebbia, of Dracula in the Provinces) seems at least superficially satisfied with Rouvigny’s alibi about wrestling with a flat tire on the way home at the time of the slaying, but Irina most assuredly is not, for all that she backs up her husband’s story while the police are in their parlor. After all, she knows perfectly well that the errand on which he would have suffered his supposed automotive mishap was a tryst with his now-dead young mistress. So you can imagine how Irina takes it when the killer strikes again, this time butchering Brenda on the premises of the Chateau Rouvigny itself. Once again Oliviero denies having anything to do with the crime, but he nevertheless knows how this looks. Rather than calling the police, or permitting Irina to call them either, Oliviero forces his wife to help him conceal the murder. Brenda’s body gets walled up in the wine cellar, and anyone who asks is told that she just up and left, presumably running off with some boy. Dario (Riccardo Salvino, from Emanuelle in America and The Lonely Violent Beach), the dirtbike-racing hippy milkman, is especially sorry to hear that. Brenda was among his steadiest lays, although there certainly wasn’t anything serious between them.

Shortly after the second murder, two new girls arrive in town. One is a teenaged prostitute named Giovanna (The Sensuous Sicilian’s Enrica Bonaccorti) destined to become the Black Glover’s third victim, while the other is Floriana (Edwige Fenech, from The Case of the Bloody Iris and 5 Dolls for an August Moon), Oliviero’s tough-as-nails niece. While the hooker sets up shop with an aging madam who may also be her aunt (Ermalinda de Felice, of Night Nurse and How to Seduce Your Teacher), Floriana drops in at the chateau. You will not be surprised, I think, at how happy Oliviero is to have a beautiful young girl show up on his doorstep looking to be taken in, or that his reaction is totally unaffected by the girl in question being a close blood relative. Meanwhile, a sinister man in an outrageously awful silver wig (Ivan Rassimov, from Shock and Emanuelle in Bangkok) starts hanging around the vicinity of the chateau, behaving in ways seemingly purpose-designed to give the Rouvignys the willies. Maybe he’s the Black Glover instead of Oliviero?

No! And what’s more, Rouvigny isn’t the killer, either! In fact, Gently Before She Dies disposes of that entire plot thread early in the second act, when the Black Glover comes for Giovanna, only to be slain in turn by her deceptively formidable old madam. The culprit turns out to be none other than Bartello the bookseller, subsequently revealed to have been an escaped mental patient living under an assumed name. So what is this movie going to do with its time now that it can no longer function as a giallo? It’s going to get serious about turning “The Black Cat” upside down, inside out, and sideways, that’s what! Floriana takes up with Dario, Oliviero, and Irina all at the same time, obviously playing some complicated game calculated to end with her in possession of whatever remains of the Rouvigny fortune. Oliviero continues being an absolute rat-bastard, in all the ways that Poe fans will recognize as characteristic of the source tale’s drunken, violent, and ultimately uxoricidal narrator. Wig Doofus steps up his lurking considerably. But the focus of your attention really ought to be on Irina. Despite her brittle, fragile appearance, she’s up to even more than Floriana— as Poe fans, again, will start to suspect when she, and not her husband, plays the narrator’s part in this movie’s version of the infamous kitty eyeball-gouging scene.

I would never have guessed that Sergio Martino had it in him. Up to now, the best movie of his that I’d seen was his close-enough-for-government-work cannibal gut-muncher, The Mountain of the Cannibal God, and the great majority of his output to come my way had been delirious bullshit like American Rickshaw and After the Fall of New York. Meanwhile, the film most directly relevant to setting my expectations going into Gently Before She Dies was that commendably nasty but smooth-brained turkey, Torso. None of those films remotely prepared me to see one of my favorite horror stories of the 19th century cleverly deconstructed into an utterly amoral exercise in all seven of the Deadly Sins. And maybe it’s just because I watched Gently Before She Dies as the parting shot of an eight-film program of gialli at the Riverside Drive-In outside of Pittsburgh, but it delighted me to see such a film treat its very genre as a red herring, resolving the serial killer subplot shockingly early on, in a manner guaranteed to draw the attention of its typically outmatched police away from the tangle of equally deadly schemes and counter-schemes that comprises the main action.

Mind you, viewers who want characters they can safely identify with will find Gently Before She Dies rough going. Everyone’s a villain, everyone’s a victim, and everyone but Irina is a patsy, too, in one way or another— and even she allows herself to look like a patsy for much of the film. It’s discomfittingly difficult to tell where Martino’s own sympathies lie, let alone where he’s trying to aim ours. By the time he reveals that these people are all despicable, and that that was the whole point all along, everyone but the true connoisseurs of 70’s skuzz will probably have long since checked out. We might say, then, that Gently Before She Dies is Sergio Martino’s Twitch of the Death Nerve, with the caveat that Martino doesn’t have anything approaching Mario Bava’s level of sheer style. Martino also lacks the ironic detachment which Bava brought to his final pure giallo, so that the audience for Gently Before She Dies has no cue to expect the jet-black shaggy dog story that’s headed their way.

Then there’s the matter of the three core performances. They’re all great, but in ways that’ll make you feel like you want a hot shower after the closing credits. Luigi Pistilli is playing a darker version of the kind of man who so often turned up as the hero in that strain of postwar literary fiction that I’ve come to think of as the Great Mid-Century Penis Chase. He’s a tightly-wound ball of thwarted entitlement, macho insecurity, and indiscriminate horniness, and within a handful of scenes, you know exactly the sort of fifth-rate Kerouac-wannabe shit that Oliviero Rouvingny must write. Edwige Fenech, meanwhile, makes a superb femme fatale, unapologetically bitchy, nakedly selfish, undisguisedly dangerous, and sexy as hell. Her personal magnetism more than makes up for the crass obviousness with which Martino positions Floriana as the movie’s evil chessmistress until such time as he’s ready to reveal that that, too, was misdirection, and that Irina’s been three moves ahead of her from the start. But the nature of that final reversal, to say nothing of its success, means that Anita Strindberg’s performance is at once the most effective and the most difficult to appreciate. That is, in order for Irina to do what she does, Strindberg has to spend the whole movie seeming to be a barely coherent mix of simpering damsel in distress and hysterical madwoman. It looks profoundly obnoxious in comparison to Fenech’s supple self-possession, and comes repulsively close to implying that Martino agrees with Oliviero that he’s the aggrieved party in their relationship. Again, though, this is all an act on Irina’s part, and it’s necessary to the third-act twist that she seem alternately helpless and non compos mentis. The temptation to write Strindberg off as a flailing she-ham is thus paradoxically the surest indication that she’s hitting exactly the right note. All in all, I’m a lot more curious now to see Sergio Martino’s previous three gialli than I was a month or so ago.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact