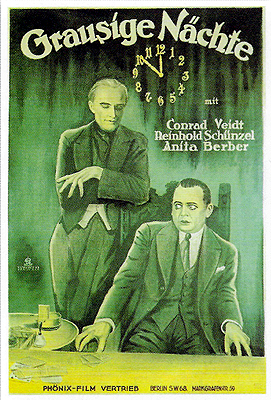

Weird Tales / Eerie Tales / Tales of Horror / Tales of the Uncanny / Five Sinister Stories / Unheimliche Geschichten / Grausige Nächte (1919) **

Weird Tales / Eerie Tales / Tales of Horror / Tales of the Uncanny / Five Sinister Stories / Unheimliche Geschichten / Grausige Nächte (1919) **

Rarely does one have to wait long after finding what seems to be the first of something before an even earlier example comes to light, but that said, I have a hard time imagining that there are too many horror anthology movies out there predating Weird Tales. At the very least, an anthology requires something close to a modern feature-length running time, and movies much longer than an hour were still a fairly recent innovation in 1919. In any event, Weird Tales pushes back the temporal horizons of more than just the portmanteau fright film, for it features Conrad Veidt in the sort of role that would dominate his historical public image, yet it came out some months before The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. It also stands as an early example of an approach to casting that would recur among anthologies at least until the days of Trilogy of Terror— not only Veidt, but his two costars as well appear in all five tales, plus the interstitial framing sequences.

Those framing bits concern an antiquarian bookshop, where wall-hung paintings of Death (Veidt, from Madness and The Student of Prague), the Devil (Reinhold Schünzel, from Figures of the Night and Dragonwyck), and a whore (Anita Berber, from Dr. Mabuse the Gambler and The Count of Cagliostro) come to life after hours, and scare the proprietor clear out the door. The animate figures then begin rifling the merchandise in search of suitably macabre stories with which to amuse one another.

The first tale is arguably the most modern, concerning itself less with such commonplace agents of horror as ghosts or maniacs than with an unsettling restructuring of reality as its protagonist has understood it. While walking in the park one afternoon, a man (Veidt) encounters an attractive young woman (Berber) who tells him that her husband has gone mad. They’re divorced now, but he will not accept that, and he continues to follow her wherever she goes. And if I’m interpreting the ensuing flashback correctly, the impetus for the couple’s breakup was a sudden and unmotivated attempt by the husband to garrote her in their living room. No sooner have Veidt’s and Berber’s characters made their mutual acquaintance than a wild-eyed man in a long, black coat (Schünzel) lunges at the woman from some bushes beside the path— that would be hubby, I’m guessing. The first man drives the lunatic off, after which he escorts the woman to a nearby hotel, presumably with an eye toward helping her dodge her homicidal husband more effectively. She takes room 117, while he sets himself up in 328 upstairs. The man then goes out for the evening, not returning to the hotel until 2:00 AM. You might think you know what’s coming when the woman’s husband manages to track her to her hiding place, but writer Anselma Heine (each segment has its own scenarist) has something a little different in mind. The woman is indeed gone from her room by the time her self-appointed protector gets back from his night on the town, but when he raises an alarm with the hotel staff, they tell him that room 117 has been vacant for days. Even the clerk who signed the couple in earlier now swears that the man checked in alone. And when he goes to the police to file a missing person report, the vanished woman’s deranged husband follows along and accuses him of doing away with her! Franz Kafka would have approved heartily…

Next up is a more conventional ghost yarn. Two men are in competition for the same extremely flirtatious (and perhaps even promiscuous) woman (Berber), but their immense machismo won’t permit them to do anything so sensible or enlightened as simply pressing her to decide between them. Instead, they confront each other, and agree upon a scheme to remove one or the other of them from the running. The men literally stake their romantic prospects on a roll of the dice, but the one who loses the toss (Schünzel) is even less honorable than the enterprise would imply in the first place. He strangles his rival (Veidt), and carries on his wooing unopposed. The dead man’s spirit is justifiably resentful, however, and the killer soon finds that he keeps seeing his victim’s hands or face in the shadows and out of the corners of his eyes. That would be bad enough all by itself, but his girlfriend turns out to be big into spiritualism, and her idea of the perfect date is to drag him along to a séance…

You’ve heard this next one before. At a beer hall someplace, one of the customers (Veidt) wistfully observes that the mean-tempered drunk over in the far corner (Schünzel) has an exceptionally lovely wife (Berber). That wife, meanwhile, has a pet black cat whose company she understandably much prefers to her husband’s, and that pisses the big lush off more than just about anything. The man from the bar befriends the put-upon woman, and their relationship quickly starts inching from friendship toward affair status. When the husband finally sticks his head far enough out of the bottle to figure out what’s been going on, he goes berserk and murders his wife; her body goes into an alcove in the cellar, which he walls up to match the surrounding plasterwork. The killer gives little thought to the disappearance of the cat at about the same time, but the animal’s whereabouts will become a matter of considerable importance when the dead woman’s boyfriend becomes suspicious enough to bring the police by to search the house…

Now from Edgar Allan Poe to Robert Louis Stevenson. There’s an exclusive club in town which one man (Schünzel) wants to get into so badly that he eventually scales the second-floor balcony after being turned away by the doorman who knows how many times. The club president (Veidt) seems willing enough to admit him now that he’s here, but his sister (Berber) implores him to send the gate-crasher packing, protesting that he doesn’t know what he’s getting himself into. Both men blow her off, but Mr. Balcony-Climbing Guy is about to wish he hadn’t. You see, at each meeting of the club, the president passes around a deck of cards as the last order of business, and whoever draws the ace of spaces is required to die that night…

And finally, a bit of whimsy. Sometime during powdered-wigs-and-rapiers days, a baron (Veidt) and his wife (Berber) take in another nobleman (Schünzel) whose carriage wiped out on the road leading past their castle. The baroness is bored and dissatisfied in her marriage, and makes no secret of preferring the new guy, with his virile bearing and his tall tales of duels, wars, and other manly exploits. Still, the baron seems completely untroubled at the prospect of being cuckolded in his own castle, and when he is called upon to report to the court of a higher-ranking noble, he blithely leaves his wife and her new boy-toy together unsupervised. Then again, maybe the baron knows what he’s doing. Loverboy may be brave beyond reproach in the face of swords and muskets, but how do you challenge spook-possessed furniture to pistols at twenty paces…?

For the most part, these are slight stories, told with little flair and a sameness that grows tiresome by the end. Weird Tales is an understandably primitive movie, and archaic features like the stilted acting and the scant and sketchy intertitles reinforce the tendency of the five segments— all of them built around the same three actors, and four of them hinging on love triangles turned hellish— to blur together. With such rigidly stylized acting and next to no dialogue except in the fourth and fifth stories, there is little basis upon which to draw distinctions among the three different Veidt-assayed characters who come between men and their lovers, the three different unpalatable husbands/boyfriends played by Schünzel, or Berber’s four mostly interchangeable sex objects. Indeed, even on the occasion when Veidt’s and Schünzel’s usual roles are reversed, their virtually identical costumes and makeup render it hard to pick up on the switch. The individual stories can be difficult to follow, too, with the paucity of intertitles again being a major factor. It usually takes five minutes or more for enough clues to surface to permit more than the wildest guess at what’s going on in any given segment, leaving each character’s first few actions bafflingly divorced from context. The “Wait— why is that guy climbing up the balcony?” moment early in the “Suicide Club” episode provides perhaps the most conspicuous example. Finally, the edition most readily available in home video today (a small-batch, gray-market DVD-R version apparently derived from an earlier VHS issue) is of such miserable quality as to interfere markedly with one’s appreciation of what merits this movie possesses. Contrast is eye-strainingly high, and the image is tinted a dense, murky red that only exacerbates the problem. (I assume the tinting is deliberate, since I can’t imagine how black and white film would fade to red no matter how badly it was treated, but I suppose there might be some decay process I don’t know about that could account for it.) Foreground objects are washed out and devoid of detail, background objects are frequently altogether invisible, and in general, it’s very difficult to figure out quite what you’re supposed to be seeing at any given moment. Also, while The Ring of the Nibelungen isn’t the worst possible musical accompaniment to a movie like this one, it sure as hell doesn’t fit the mood.

Even so, Weird Tales remains interesting as yet further illustration of how far ahead of the curve the German film industry was during and for several years after World War I. Its director, Richard Oswald, has a remarkable resumé, including pioneering efforts in several fields not typically associated with the teen years of the 20th century. In addition to this horror anthology made some four decades before the heyday of such things, Oswald shot two versions of The Hound of the Baskervilles, an adaptation of The Picture of Dorian Gray, a vampire film predating Nosferatu by six years, and a succession of sensationalized “social issues” pictures roughly akin to what the American roadshow industry would specialize in during the 1930’s. Most notable among the latter are the four-part Let There Be Light series (a rather more high-minded precursor to the vast corpus of German sex schlockumentaries from the 1970’s), the two-parter Prostitution, and 1919’s groundbreaking Different from the Others, a heartfelt call for the repeal of Paragraph 175, Germany’s draconian anti-homosexuality statute. Different from the Others is all the more noteworthy considering that there is no indication that Oswald himself was gay. The sex-awareness movies landed their creator in a lot of trouble after the German government reinstated film censorship in 1920, and by the time the Nazis rose to power, Oswald’s situation was utterly untenable. He fled to America, but enjoyed little success in Hollywood. Meanwhile, back home, the Nazis made a big production of burning every copy of his movies that they could find, with the result that many if not most of them have vanished without a trace. Different from the Others, for instance, is now known only from the 40 minutes or so that were incorporated into the later semi-documentary, The Laws of Love. So while Weird Tales may not be especially good in its own right, it nevertheless has value as a sample of the work of one of early German cinema’s great forward-thinkers.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable focusing on the olden days, when you had to bring along your reading glasses when you went to the movies, but never had to contend with the booming of the explosion flick in the auditorium nextdoor intruding upon your enjoyment of the sensitive relationship drama you were trying to watch. Click the link below to peruse the Cabal's collected offerings, and don’t mind the smell— that’s just the nitrate in the film stock rotting away to vinegar vapor before our noses...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact