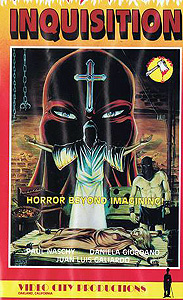

Inquisition/Inquisición (1976) **

Inquisition/Inquisición (1976) **

It surprises me a bit that it took until 1976 for Paul Naschy to get around to making a Conqueror Worm-style witch-burner. That was awfully late in the game for such things, the cycle having peaked years before, around the time of the Mark of the Devil movies. But what’s more surprising still is that Naschy, who wrote and directed as well as starring in the Vincent Price/Herbert Lom role, attempted to do much more with his entry into the field than simply copy the most successful of his predecessors. For though there is indeed much about Inquisition that is more or less openly stolen from earlier witch-hunting movies, the basic perspective of the film is something I’ve seen nowhere else. While most of these movies take the simple and facile position that the Inquisition and its Protestant counterparts were corrupt and evil institutions made up of corrupt and evil men, Inquisition gives its main witch-hunter a little room to be pitied himself, and shockingly admits that a fair percentage of his victims really are heretics and devil-worshippers, even if it also maintains that the Church’s official understanding of heresy and devil-worship during the Middle Ages was completely off-base.

Inquisition begins by reminding us, as if such a thing were necessary, of just how much life during Medieval times sucked. As inquisitors Bernard de Fossey (Naschy, of Horror Rises from the Tomb and Jack the Ripper), Nicolas Rodier (Ricardo Merino, from Trauma and Kilma, Queen of the Jungle), and Pierre Burgot (Tony Isbert, from Rest in Pieces and Red Rings of Fear) trudge across the French countryside toward the village of Peyriac, they pass by vistas of uninterrupted misery, poverty, and suffering, climaxing with a short stop in a hamlet which has been almost totally depopulated by the Black Death. Meanwhile, in Peyriac itself, Catherine (Daniela Giordano, of Sexy Susan Sins Again and Gently Before She Dies), the daughter of the nobleman with whom Fossey and his associates will be staying, is enjoying a secret rendezvous with her boyfriend, a young man named Jean Duprat (Guyana: Cult of the Damned’s Juan Luis Galiardo). Jean and Catherine have been keeping their courtship on the down-low because up until recently, he was much too poor to vie openly for the hand of a count’s daughter. But with the plague working its implacable will on the land, Jean’s prospects for inheritance have gotten a whole lot better; he is now the first in line to claim the Duprat family’s main estate, and its present owner is unlikely to live very much longer. In fact, within the next couple of days, Jean is going to leave town for a visit to his uncle, who has offered tentatively to lend him the money he will need to make his case as a suitor before Count Albert (Eduardo Calvo, from The Erotic Rites of Frankenstein and The House of Psychotic Women). Those of you who have seen The Conqueror Worm will be making some very grim predictions for the couple’s future at this point.

Sure enough, the moment Fossey and his boys arrive at the count’s castle, the inquisitor takes notice of Catherine, and begins leering at her with increasing openness each time the two of them cross paths. Meanwhile, Alobert the one-eyed bum (Antonio Iranzo, from Hidden Pleasures and Island of the Damned) starts spending a lot of time in the company of Fossey’s lieutenants, telling them incriminating stories about Peyriac’s young women. Naturally his aim is to get even with all the village cuties who have rejected his efforts to get into their pants over the years. The surprising truth is that there really is a coven of witches active in Peyriac, however, and some of its adherents are members of Count Albert’s household. In particular, Catherine’s lady in waiting, Madeleine (Mónica Randall, of The Witches’ Mountain and The Devil’s Cross), is a closet witch, and frequently goes to coven leader Mabille (Tota Alba, from The Possessed and Strange Love of the Vampires) for charms, potions, and incantations meant to work some manner of benefice for her mistress. Needless to say, the magic practiced by Madeleine and Mabille becomes increasingly less gentle with each new girl who winds up in Fossey’s torture dungeon on the basis of Alobert’s denunciation.

Then comes the subplot that will bring Catherine herself into the Satanist fold. While Jean is on the road to his uncle’s place, he is set upon by highwaymen and murdered. The authorities would have it that Jean’s death was incidental to a robbery, but only a few days after she hears the news, Catherine has a vivid dream in which she sees Jean’s killers being paid off after performing the deed by a man in a hooded cloak, whose face she is unable to see. Catherine interprets her dream as a message sent by Jean from beyond the grave, and she tells Madeleine all about it, vowing to do anything within her power to learn the identity of the man who instigated the murder. Madeleine, ever eager to please, brings Catherine out to Mabile’s shack, where the arch-witch begins Catherine’s indoctrination into devil worship. Unsurprisingly, when Catherine finally gets her diabolical vision revealing the face of the man behind Jean’s murder, it’s Fossey she sees beneath the heavy cowl. In a sense, this is terribly convenient, because the inquisitor’s eagerness to violate his vows with Catherine means that he’ll be more than willing to let her get close to him, and when you get right down to it, there could hardly be a more fitting revenge against an agent of the Inquisition than to lead him into an illicit romance with a practicing Satanist. If she plays her cards right, Catherine can get Fossey damned, defrocked, and executed for apostasy, all in one go. On the other hand, little sister Elvire (Julia Saly, from Night of the Seagulls and Night of the Werewolf) is getting extremely worried about the ever more provocative statements of Satanic faith which Catherine has been making ever since her conversion, and Emile the surgeon (Antonio Casas, of No One Heard the Scream and The Sound of Horror), a longtime friend of the family with an anachronistically rationalist turn of mind, is on the lookout for some way to prove that witchcraft and devil worship are really nothing more than a desperate effort on the part of the powerless and downtrodden to assert some kind of influence over a world that has fucked them good and hard at every opportunity. At first glance, a count’s daughter might not seem like a good test case for Emile’s theory, but Catherine did just suffer a tremendous and senseless trauma, after all.

I’m pretty sure I’ve never seen another horror movie that deals with the subjects of Medieval witchcraft and the efforts of organized religion to stamp it out in quite the same way as Inquisition. Taking neither the conventional “innocent women beset by corrupt churchmen” angle nor its obvious opposite, it argues instead that inquisitors and “witches” alike are essentially victims of insane and brutal times. Fossey may be corrupt, but he knows that better than anyone, and it causes him enormous anguish to recognize that he has betrayed everything the Church supposedly stands for. Not only that, we learn in the end that he almost certainly was not guilty of the crime for which Catherine engineers his downfall, although his long career with the Inquisition obviously gives him plenty to answer for. His minions, meanwhile, though no less brutal than their counterparts in any similar film from the era, are depicted as being not so much evil as intellectually blinkered; their problem is that they are simply not capable of thinking outside the rigid framework of a thuggish and debased culture. Most interesting of all is the way Inquisition handles its witches. With the exception of a few girls who are denounced by Alobert for no better reason than that they would never consider sleeping with him, the women Fossey rounds up to torture really have rebelled against the Church and the society it supports. But even they are so thoroughly conditioned to the Medieval Catholic mindset that they can conceive of rebellion only on the Church’s own terms; rather than becoming revolutionaries, they become witches and heretics. Notice, however, that the film gradually reveals that these witches have no power. Their spells, their charms, their communion with Satan— all of it springs from the effects of homemade psychoactive potions on minds which are desperate to believe they can hold some kind of sway over the world. I suppose it makes some sense that Paul Naschy would be the one to make this remarkably independent-minded witch-burner, in that he almost always sought ways— and frequently very unconventional ones— to drum up some sympathy for the villains he portrayed. Within the framework of this story, Fossey is incapable of being as devilishly odious as The Conqueror Worm’s Matthew Hopkins or Mark of the Devil’s Lord Cumberland, and it seems fitting that he gets to have a moment of quiet, penitential dignity on his way to the stake at the movie’s end.

It’s just unfortunate that Naschy and his cohorts fumbled so much in bringing their unique ideas to the screen. The writer/director/star himself put in what was, for him, an exceedingly good performance all around, but exceedingly good for Paul Naschy is sadly a fair sight short of exceedingly good in general terms. For every scene like Fossey’s ride to the pyre, there are two or three like the ludicrously clunky Sabbat, in which a rather listless and poorly-attended orgy is presided over by a man-in-a-suit Satan that makes the one from The Devil Rides Out look like Tim Curry’s Darkness in Legend. The eventual showdown between Alobert and the last of his comely young enemies both starts and ends rather well, but in the middle, it takes a sharp detour through abject silliness. The combination of Daniela Giordano and the woman who was hired to dub her for the English-language version is a most lamentable one, in that neither one of them appears to have had a performance setting intermediate between robotic inertia and Barrymorean overdrive— and since Catherine gets more screen time than any other character, it’s really a wonder the movie can survive her at all. Ultimately, the best I can say about Inquisition is that it was a good try.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact