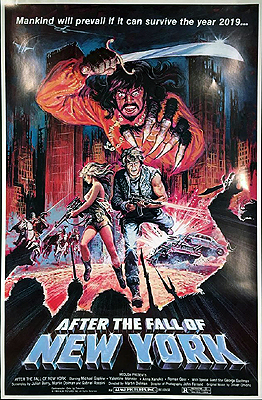

After the Fall of New York / 2019: After the Fall of New York / 2019: Dopo la Caduta di New York (1983/1984) -***

After the Fall of New York / 2019: After the Fall of New York / 2019: Dopo la Caduta di New York (1983/1984) -***

I don’t know why I didn’t think of this before. I mean, surely 2019 can’t have been the first chance I’ve had to ring in the new year by reviewing an old sci-fi film set during it. I’ve got the idea now, though, so as my first review of 2019, I give you 2019: After the Fall of New York.

For a long time, I was under the mistaken impression that After the Fall of New York was a second sequel to 1990: The Bronx Warriors— and I suspect that the people responsible for this picture would have been happy enough to let me go on believing that. After all, Enzo G. Castellari’s movie made enough money to be worth ripping off in its own right. Thus although Sergio Martino’s vision of New York’s future is more avowedly futuristic than Castellari’s, it’s still broadly compatible. Both foretell a city of brutal yet ineffectual authorities and flamboyantly bizarre street gangs, and draw as much upon Walter Hill’s The Warriors as they do upon more obvious dystopian touchstones like Escape from New York and The Road Warrior. Martino just goes the extra mile with his mutants, robots, cyborgs, and Mengelic medical experiments, together with a premise that prefigures Children of Men.

One might argue that After the Fall of New York dabbles a bit in alternate history, too, since it’s difficult to see how we’re supposed to get from the real world of 1983 to the fictional one destroyed by the nuclear war of this movie’s back-story in just sixteen years. The contenders in that world-wrecking conflict were not the United States of America and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, you see, but a pair of hemisphere-spanning super-states called the Pan-American Confederacy and the Euro-Asian-African Coalition. There was more to the war, too, than the then-standard exchange of ICBMs. The apocalypse involved plenty of conventional fighting on land as well, which lasted long enough for each side to introduce markedly unconventional troops toward the end: robots on the EURAAC side, and more sophisticated cyborgs for the PAC. The opposing armies conquered and occupied each other’s territory, and in the most unexpected of all divergences from the standard model of 80’s nuclear holocausts, this World War III had a clear winner. Not that the EURAAC benefited much from smashing the rival power. The radiation unleashed by all those H-bombs had a catastrophic effect on human fertility, so that nothing but mutants were born anywhere on Earth for the first five years after the fallout settled, and then no infants at all ever since. Most average people seem too brutalized to care very much about the impending slow demise of the human race, but the EURAAC leaders don’t intend to go gentle into that or any other good night. Their occupied territories in the western hemisphere consequently live under a tyranny unlike any previously experienced in history, with the entire native populations liable at any time to be rounded up for medical experiments aimed at restarting human reproduction.

Nevada isn’t one of those places, however. It’s just a lawless no-man’s land where life is cheap and murder is an organized sport. A rising star in the latter field is a former PAC special-ops soldier called Parsifal (Michael Sopkiw, of Devilfish and Massacre in Dinosaur Valley), whom we meet as he’s about to enter a demolition derby to the death against a whole team of seasoned automotive killers. He makes pretty short work of them, and then rides off into the desert with his prize— a girl by the strikingly inapt name of Flower (Siriana Hernandez)— on the back of his comically huge motorized tricycle. Parsifal was plainly not expecting to be accosted at that point by two men in a futuristic hover jet, but he strangely seems not to be altogether surprised, either. The flyboys claim to be from a newly reorganized Pan-American Confederacy, headquartered in relatively un-nuked Alaska. The president himself sent them to recruit Parsifal for an urgent and top-secret mission. Seeming more peeved than anything else, Parsifal turns Flower loose to fend for herself and boards the PAC hover jet.

It isn’t clear exactly how, but Parsifal and the new PAC president (Edmund Purdom, from Pieces and The Sinister Eyes of Dr. Orloff) unmistakably have a history together, and that history just as unmistakably involves the president habitually levering Parsifal into doing things that he’d never consent to do freely. That’s just what happens this time, too. The PAC’s spies have heard a rumor too good not to be followed up, no matter how unlikely it sounds: somewhere, somehow, there’s one fertile woman living in New York City. New York, inconveniently, is under EURAAC occupation, so for all anyone knows, she could be awaiting vivisection even now. The president considers it vital to PAC interests— to human interests, even— to locate the world’s last working womb before the EURAAC does, and to spirit its owner away to safety. That’s where Parsifal comes in. Oh, he won’t have to do it alone. He’ll have the help of Bronx (Paolo Maria Scolandro, from Sleepless), who as you might guess from that name is a native of the city, and Ratchet (Romano Puppo, of The Great Alligator and Escape from the Bronx), “the strongest man in the Pan-American Confederacy.” Furthermore, the president has a carrot to go along with the sticks he’s been brandishing. Although the long-range objective of the mission to New York is obviously to restart the human race, the leader of the new confederacy understands as well as anyone that it’s pointless to try repopulating the poisoned Earth. The PAC leads what remains of the world in astronomy, however, and its scientists discovered years ago that there are several habitable worlds circling Alpha Centauri. In fact, they discovered that enough years ago that there is now waiting a spacecraft of sufficient size, range, and power to carry a few hundred deserving passengers to the star next door for a brand new beginning. If Parsifal can bring back the last fertile woman on Earth, he’ll have a seat on that ship right alongside her.

This is the point at which After the Fall of New York begins borrowing in earnest from The Warriors, by which I mean that it now congeals into a loosely structured succession of episodes in which Parsifal, Ratchet, and Bronx encounter one tribe of freaks after another. First, they’re captured by the Rat Eaters, whose chief (Hal Yamanouchi, from Hearts and Armour and 2020 Texas Gladiators) intends to make a feast of them for his people. Rescue of a sort comes in the form of a EURAAC cavalry patrol, which massacres the Rat Eaters and takes the PAC captives into their own custody. The horsemen also pick up a girl named Giara (Valentine Monnier, who was also in Devilfish), who alone among the Rat Eaters is not covered all over with scars and pustules. Maybe she’s the fertile one, eh? A medical examination seems to rule that out, but Parsifal’s determination to bring Giara along when he and his comrades escape persuades both the EURAAC governor (Serge Feuillarde) and his right-hand woman, Ania (Anna Kanakis, from Warriors of the Lost World and Attila, the Scourge of God), that their lab must have given them a false negative.

In their flight from recapture, the fugitives (minus a casualty or two) befriend both a tribe of dwarves and a tribe of semi-simian mutants led by the formidable Big Ape (George Eastman, of The Barbarians and Emanuelle Around the World). These are even better allies than they look, for two reasons. Not only is Big Ape as strong and as fierce as his namesake, but he also believes himself to be fertile. And of at least equal importance, a dwarf called Shorty (Louis Ecclesia)— who is ironically taller than most of his fellows— has actually met, in a manner of speaking, the girl for whom Parsifal came looking. She’s the daughter of a reclusive scientist, who placed her in suspended animation when the war began. Shorty is probably the only person in all of New York for whom the professor will open the door to his secret bunker, so meeting him turns out to be the key to Parsifal’s entire mission. Now it’s just a question of reaching said bunker alive, and absconding to safety with its occupants.

I feel reasonably confident in claiming that After the Fall of New York is the only movie you’ll ever see in which an unconscious girl getting raped by an ape-mutant counts as a happy ending, or at least as the setup for one. Praise or condemn that as you like, but that’s the kind of picture we’re dealing with here. It’s also the most purely gonzo We Have Seen the Future and It Sucks flick to come my way in many a year, and seeing it rekindles my enthusiasm for the junkier strata of the subgenre. As those two statements should combine to suggest, After the Fall of New York is a baffling mix of the bleak and the giddy, in which terrible things are forever happening in the zaniest possible way. Story logic, meanwhile, is in such short supply that I had to forego mentioning one of Parsifal’s major character motivations— his deep-seated loathing of cyborgs— because to introduce it during the synopsis would merely have raised questions that I’d be powerless to answer. Whenever it comes up, it does so out of nowhere, and drives Parsifal to actions completely counter to all his other purposes— and what’s more, we never even learn the cause of his sometimes literally murderous prejudice. After the Fall of New York is strangely unclear, too, on whether humanity’s fertility problem encompasses the male of the species, or whether post-apocalyptic barrenness is strictly a women’s issue. Big Ape brags constantly about his ability to “make babies” (how would he even know?!), which doesn’t make a lot of sense unless most men can’t. But if men are infertile, too, then what’s the point of the PAC space ark? Or are we meant to conclude that fertility, and not useful skills and knowledge, is the criterion for inclusion among the colonists to Alpha Centauri? Honestly, I don’t think Sergio Martino or any of his several co-writers know, either.

All of the above is more or less par for the course for Italian exploitation movies of the 1980’s, as any habitual viewer of the things can attest. But After the Fall of New York has also brought into focus for me another common feature of such films that I’d never fully appreciated before. No one but early-80’s Italians so consistently managed to find leading men so boring and unremarkable that the mere casting of them as larger-than-life heroes warps them around to become perversely interesting. Take a good look at Michael Sopkiw. This guy has no exceptional qualities of any kind, or at least none that the camera can detect. But dress him in leather pants and a chainmail jacket, and insist to us over and over that he’s the one man who can save the world, and a cheap sort of cinematic alchemy occurs. No, Sopkiw never becomes a convincing hero, but you find yourself watching his performance like a hawk, searching for any trace of what inspired the filmmakers to pick him for the role. The question seems to take on fresh urgency, too, once Big Ape enters the fray. George Eastman, for all his conspicuous inaptness as a conventional movie star, possesses unusual qualities in spades, so that your attention is first drawn to him, and then pushed back toward Sopkiw to ask once again, “This guy? Really? Are you sure about that?”

It turned out that starting off the new year with an old sci-fi movie set in it was enough fun to become a running tradition— enough of one, in fact, that I decided the project needed a name and a logo. Click the banner below to see where I took it from here:

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact