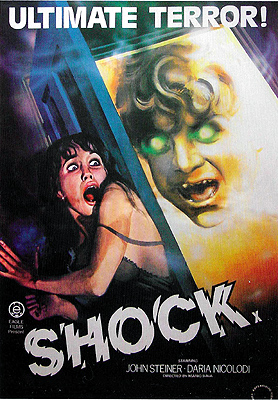

Shock/Beyond the Door II/Schock (1977/1979) ***

Shock/Beyond the Door II/Schock (1977/1979) ***

Pay no attention to what this movie’s American distributors told you back in 1979. Shock/Beyond the Door II/Schock actually has nothing whatsoever to do with the universally reviled Exorcist clone to which they tried to pass it off as a sequel that year. Instead, this film— the last one Mario Bava directed for theatrical release— is something far more sophisticated, as much about a family in disintegration as it is about ghostly (as opposed to demonic) possession.

As the movie opens, the Baldini family is moving into a huge modernist house in some outlying suburb or other. It isn’t apparent just how at this point, but the place definitely figures at some level in Dora Baldini’s past, and something about moving into the house troubles her. As we will gradually learn, Dora (Daria Nicolodi, from Deep Red and Inferno) had lived there before, about seven years ago— until shortly after her son, Marco (Beyond the Door’s David Colin Jr.— I’m guessing his presence is the reason for Shock’s faux-sequel status), was born. As for what troubles Dora about the prospect of living there again, it was also around seven years ago that her first husband, Carlo, died, apparently by self-induced drowning. (Although his body was never found, so who can say for sure?) Dora had a major breakdown shortly thereafter, and spent several years in the hospital under the care of psychiatrist Aldo Spinidi (Ivan Rassimov, from Planet of the Vampires and Eaten Alive), whom she continues to see semi-regularly even today. Dora’s current husband, an airline pilot named Bruno (John Steiner, of The Devil Within Her and Unsane), tries to assure her that she’ll adjust soon enough, but something tells me that isn’t terribly likely.

The Baldinis haven’t been in the house more than a day when the peculiar manifestations commence. Dora begins having nightmares and hallucinations involving the rather sloppily constructed brick wall in the cellar and a putrefying hand clutching at her wrists and ankles. But far more worrisome than that is what starts happening to Marco. Sporadically at first, but with increasing frequency as time goes on, Marco’s personality will seem to shift. He tells transparent lies, gets into all sorts of destructive mischief, even deliberately torments and terrorizes his mother. At one point, as if in a trance, he says to Dora, “I have to kill you, mother.” Perhaps even worse, he arranges for a florist to send Dora a bouquet of seven red roses with a note reading, “No matter what happens, you’re both still mine. One for each year…” In combination with certain things which we’ve seen, but which Dora has not, it’s enough to make you think the boy has been possessed by the spirit of his long-dead father.

And in fact he has, but that’s only the beginning. The more we learn about Carlo (he was a heroin addict, for example, and evidently had a tendency toward violent behavior when he was high), the worse it sounds for Dora and Bruno to have the dead man using Marco as his agent in the world of the living. But it also seems that the ghost may have much stronger motivations than simple jealousy, and that Dora might not be the long-suffering innocent that she initially comes across as. Finally, because this is a Mario Bava movie, it would probably be a mistake to discount the possibility that Bruno is less upstanding than he appears, too.

The first thing that’s going to hit any reflective viewer about Shock’s story is the way the filmmakers use it as a lens through which to examine serious familial dysfunction. It’s probably no accident that Shock came out in the 70’s, right when the social ramifications of liberalized divorce laws were first making themselves felt. Beyond the obvious theme of the discarded spouse’s natural jealousy toward his replacement, Shock takes a stab at the thornier issue of how the children of broken homes are affected, even when they were too young at the time to remember the rupture itself. Marco is depicted as having a very close relationship with his stepfather, but that doesn’t stop him from preferring Carlo when the choice presents itself, even to the extent of helping to destroy his mother’s second marriage. And as we see once Carlo begins manifesting himself independently of the boy, Marco is indeed a willing participant by the movie’s end. Note that this is true despite Carlo’s patent unfitness as a father— which, of course, Dora has prevented her son from ever finding out about, to her own ultimate disadvantage. Thus is Dora an effective accomplice to her own undoing, even if we disregard the secret from her past that justifies the ghost’s rage in the first place. Bruno, too, plays his part, both in his contribution to the original affront against Carlo, and perhaps in the form of a more systematic betrayal that the movie only hints at. If there can be said to be a moral to Shock’s subtextual story, it seems to be that when families fail, it leaves no one innocent in the end, regardless of who is to blame for taking the first irrevocable step. But there is another, even more disturbing, image of family gone wrong on display here, and it is this that marks Shock out as originating from somewhere other than Hollywood. This movie doesn’t flinch from the psychosexual implications of a dead man taking over the body of his own son in order to get at his still-living wife. It made my flesh crawl on each of the numerous occasions when the possessed Marco talked Dora into letting him sleep in her bed while Bruno was out of town flying his jetliner.

But enough of English class for now; let’s move on to somewhat firmer ground. When I hear the words “Mario Bava ghost movie,” I immediately imagine a gothic like The Whip and the Body. But with Shock, the standard gothic premise and plot structure have been transposed into an entirely contemporary setting, with enjoyable (albeit mixed) results. Principal screenwriter Lamberto Bava (the director’s son) has said that his main influence in crafting the story was Stephen King (who, in 1977, had appeared on the cultural radar only relatively recently), and Shock does indeed carry echoes of King’s writing, especially in the sense that the younger Bava was talking about— the modernization and domestication of traditional horror story setups most closely associated with long-ago times and faraway places. The Shining is perhaps the most obvious influence, in that like Shock, it is a haunted house tale with a young boy at the center of the action and an extremely small cast of characters, but to me at least, the film’s overall tone more closely resembles some of King’s other early work. The Baldinis, after all, are on their home territory when supernatural danger imposes upon them, and are not cut off from the rest of the world except by their own secrets. What I find really fascinating, though, is that the King novel of which Shock reminds me most strongly hadn’t even been written yet when the movie appeared on the scene. Consider: a dead man with a grudge leaves a piece of himself behind in a place to which he had been strongly tied for many years; a boy comes into that place, and gradually has his personality assimilated to that of the dead man; the boy’s loved ones begin worrying almost immediately about what is happening to him, but learn the truth of the situation only after it’s much too late to save him; and in the end, those loved ones face a fight to the finish against the malevolent spirit itself. Sound at all familiar? Sound at all like Christine?

Because of all that, Shock makes for an interesting contrast with the rest of Mario Bava’s output. He had made plenty of horror films outside the gothic subgenre, of course, but the only ones he had set in the real world of the present day were his gialli— Blood and Black Lace, Twitch of the Death Nerve, and the rest. (Actually, he may have directed one modern-day ghost story before, the “Telephone” segment of Black Sabbath. But it’s at least equally likely that that story originally had no supernatural angle at all, and that the ghost business was added by AIP’s writers to replace the “cuckolded by a lesbian” plotline which the studio’s chiefs believed [probably rightly] would be deemed unacceptable by the censorship authorities of the day.) It is thus perhaps understandable that Bava seems a bit unsure of himself here, and that neither his direction nor his cinematography has the vibrancy that I usually expect from a movie with his name on it. Nevertheless, Shock displays a hell of a lot more imagination than most of its contemporaries, and gets tremendous mileage out of many surprisingly simple tricks. The dream sequences, for the most part, are superbly realized, and the movie features some of the most skillfully crafted jolt scenes I’ve encountered in quite a while. The cast is also a big help. The child is, almost inevitably, the weak link, but both Daria Nicolodi and John Steiner put in performances far above the norm for an Italian horror film of the 1970’s. I agree with the common opinion that Shock would not serve as a particularly good introduction to Bava’s work, but it’s also much better than I generally expect from a filmmaker’s last movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact