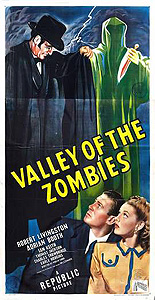

Valley of the Zombies (1946) **

Valley of the Zombies (1946) **

Well, would you look at thatÖ Turns out itís possible to demonstrate actual skill at going through the motions! Republic Pictures were the come-lateliest of all Johnnies during the second big wave of Hollywood horror, not producing a single feature-length film in the genre (even by that decadeís very lenient standard of feature length) until The Lady and the Monster in 1944. By 1946, when the studio made its last contributions to the cycle in the form of Valley of the Zombies and The Catman of Paris, the moment for such things was well and truly past, to the extent that even Universal would release only a small handful of shoddy and half-hearted horror films that year. Valley of the Zombies is shoddy and half-hearted, too, but it nevertheless displays a level of craftsmanship that had largely gone absent from Universalís output by this point, and which other Poverty Row studios like Monogram and PRC had never managed in the first place. It reminds me a bit of the made-for-TV movies of the 70ís in that respect, which is perhaps not wholly coincidental. Republic, remember, was a serial studio first and foremost. Its contract writers, directors, and performers were accustomed to grinding out tremendous amounts of product with few resources, on extremely unforgiving schedulesó exactly as their counterparts working for network television would be 30 years later. A feature filmó even a 59-minute B-picture like Valley of the Zombiesó was therefore a chance to stretch out and relax a little. What would be an occasion for high-pressure hack-work at one of the big production houses was a prestige project at Republic, and that inversion of perspective shows in this movie. Valley of the Zombies has very little either new or terribly interesting to offer audiences familiar with the past fifteen yearsí worth of cheap Hollywood chillers, but it works its way over this well-trod ground with unexpected deftness and poise, even demonstrating a touch of real wit in the process.

Somebody has been stealing blood from the clinic operated by neurologist Dr. Rufus Maynard (Charles Trowbridge, from Shock and The Mummyís Hand)ó twelve pints of the stuff over the past few days, if Nurse Susan Drake (Lorna Gray, of The Man They Could Not Hang and The Perils of Nyoka) is counting right. Neither Maynard nor his assistant, Dr. Terry Evans (Robert Livingston, from The Naughty Stewardesses and The Black Raven), can imagine why anybody would bother stealing blood, but the senior doctor doesnít have to wait very long for an answer. Shortly after Evans and Drake go out for a late dinner, leaving Maynard alone in the clinic, a caped and top-hatted man carrying a cane that certainly ought to have a sword concealed in its shaft (Ian Keith, from Fog Island and The Phantom of Paris) ascends to the roof of the building via the fire escape, and lets himself in through the maintenance access up there. When Maynard sees him and asks what heís after, the intruder forthrightly says that heís come for more blood. Itís kind of a long story whyÖ

Maynard doesnít realize this at first, but he and Count Ersatzula have met before. The manís name is Ormand Murks (no, really), and he used to be an undertaker in the nearby village of Greenwood Knoll. Somewhere along the way, and for no very credible reason, Murks became obsessed with the mechanics of life and death, especially with the possibility of an intermediate state suggested by the existence of that old nemesis of undertakers, catalepsy. He scoured the scientific literature and the occult lore of a hundred cultures, until a visit to the Valley of the Zombies in some nameless Third World hellhole provided him not only with the confirmation he sought, but with the means to bring about a controlled state of living death. Now it might seem weird on the face of it that the first thing Murks did upon concluding his quest was to try the witch doctorsí potion on himself, but thereís a significant advantage to being neither truly alive nor truly dead: in his present state, Murks is nearly impossible to kill permanently. Shoot him, stab him, strangle him, poison himó it doesnít matter. Heíll seem to be dead, but one good blood transfusion, and heíll be good as new. The downside is that regular transfusions are also the only thing keeping Murks animate, and it was the need for a dependable source of replacement blood that first brought him and Maynard together. That was five years ago, and it didnít go well. Far from granting him a transfusion hookup, Maynard understandably decided that Murks was insane, and had him committed to a mental hospital under the care of Dr. Lucifer Garland (Wilton Graff, from Pillow of Death and Strange Confession). Naturally transfusions were not an element of Garlandís treatment regimen, and sure enough, Murks was ďdeadĒ of no detectable cause within the year. Garland and Maynard both wanted an autopsy performed, of course, but Murks had stipulated in his will that his body was to be turned over untouched to his brother (Earle Hodgins). Presumably this brother knew what Ormand required under the circumstances. Anyway, Murks had lain low for the last four years, while his brother took a succession of jobs in medical establishments under various aliases, and smuggled blood out of the refrigerators to keep him adequately refreshed. In fact, he works for Maynard right now as a chemist, going by the name of Fred Mays. Well, when Murks found out who his brotherís latest employer was, he just couldnít help himself. Murks figures Maynard owes him big for that year in the asylum, and he happens to know that the doctor has his favorite blood type. No sooner has Murks finished with Maynard, though, than Mays sneaks in to steal another few pints of blood. The unexpected meeting between the brothers turns unpleasant very quickly, for Fred, whatever crimes he may have committed on Ormandís behalf, does not go in for murder. Mays gets as far as dialing the police on the telephone before Murks gets to him and demonstrates where his own limits to sibling loyalty lie.

Of course you realize what happens when people dial 911, but fall silent before reporting their emergency. Maysís call gets traced to the Maynard clinic, but Murks has already hidden his brotherís body and absconded with the doctorís by the time anyone arrives. When Detectives Blair (Thomas E. Jackson, of Behind the Mask and The Face of Marble) and Hendricks (LeRoy Mason) barge in, they find only Terry Evans and Susan Drake, who returned from their dinner a short while before, and assumed that Maynard had simply gone home for the night. Blair and Hendricks, being cops in a 1940ís B-horror movie, leap almost instantly and on no evidentiary basis whatsoever to the conclusion that Evans and Drake must have done away with their boss in order to gain control of his lucrative medical practice, but it isnít until Susan looks in the fridge to make sure no more blood has gone missing, and spills the embalmed body of Fred Mays out onto the floor, that the pair are taken into custody. And to the surprise of no one except possibly Blairís lieutenant (Charles Cane, from The Lady and the Monster and Revenge of the Creature), the detectives are so completely brain-dead that they continue to treat Evans and Drake as the prime suspects even after a pair of patrolmen catch Ormand Murks burying Maynardís bodyó embalmed just liked Maysísó in the Greenwood Knoll cemetery, but fail to apprehend or even to get a good look at him. The lieutenant, however, is amazingly not an imbecile, and he orders Blair to release the couple.

Nevertheless, Terry knows that the cops will come back again for him and Susan on the slightest pretext, and with that in mind, he proposes that they solve the case on their own. Luckily for them, Murks left behind one hugely important clue that inevitably escaped the notice of the idiot detectives. In the trash can behind Maynardís desk, Susan finds the contents of the undead killerís old case file, which mentions Greenwood Knoll by name. Understandably, the two would-be sleuths donít begin to suspect as yet whatís really going on, but they rightly deduce that there must be some significance to the murderer trying to hide Maynardís body in the same place where Murks was sent to be buried. And they know theyíre on the right track come the evening following their release from police custody, when the radio news reports that Dr. Lucifer Garlandó also mentioned by name in the Murks case fileó has disappeared. Clearly the thing to do at this point is to swing by Greenwood Knoll for a look at the long-abandoned Murks mansion.

Thatís rightó itís a spooky house movie, and a vampire movie, and a voodoo movie, and a mad science movie, all in just under an hour! With all those elements crammed so tightly together, I can almost forgive Valley of the Zombies for its conspicuous lack of both valleys and zombies. Itís even sort of a murder mystery, in the sense that its main focus for most of the brief running time is on Terry and Susanís efforts to get to the bottom of their bossís death, even though we already know what theyíre trying to find out. The latter probably made Valley of the Zombies look distinctly retro even in 1946; in any case, its reliance on early-30ís styles of presentation is plainly apparent from the vantage point of the 21st century. Today, whatís most interesting about this movie is probably its sense of humor on one hand, and Ian Keithís portrayal of Ormand Murks on the other.

As with the majority of pre-1950ís films that show a pronounced strain of spooky house DNA, Valley of the Zombies spends a lot of its energy trying to elicit laughs alongside the screams and shivers, and as usual, a cowardly sidekick is the primary agent of those efforts. I donít think Iíve ever seen that ignominious duty entrusted to the heroís girlfriend before, however, and it does illuminating things to the movieís tonal balance whenever Susan Drake puts on her Mantan Moreland hat. To be perfectly honest, though, I canít tell for sure whether the contrast Iím seeing is more a matter of the filmmakers treating a white woman with less contempt than they would a black man, or of the standard 40ís B-movie heroine being such a complete non-entity that even a buffoonish individual personality is an improvement. All I can say for certain is that Susanís ífraidy-cat one-liners sounded wittier than any comparable dialogue Willie Best was ever given to recite, and that I expect to remember Lorna Grayís performance a lot longer than Iíve ever remembered one of Valerie Hobsonís or Evelyn Ankersís. This version of the idiot cop is a tad unusual, too, in that Detective Blair has a thing for overblown wordplay: ďLetís go over to Dr. Maynardís office, and see if we can pick up a clue that will lead us to this peculiar party who has a passion for pickling.Ē Thatís not to say that it works, mind you (the aforementioned line in particular gives Thomas E. Jackson a whupping that would move the Marquis de Sade to compassion), but at least itís a departure from the most rigid interpretation of the formula.

As for Keith and Murks, the main curiosity concerns the link between this role and one that Keith didnít get a decade and a half earlier. Along with Conrad Veidt, William Courtenay, and Lon Chaney Sr., Ian Keith was among the actors in the running for the title role in Dracula before Bela Lugosiís desperation to transfer his stage portrayal to the screen made him too good a deal for Universal to pass up. Ormand Murks isnít exactly a vampire, obviously (instead of drinking blood, he transfuses it into his veins via the embalming rig that I can only assume he carries around in the hip pocket of his trousers), but heís pretty close to it. His costume and overall appearance are unmistakably patterned after the Universal Dracula, tooó specifically, theyíre patterned after John Carradineís Dracula in House of Frankenstein and House of Dracula. Of course, that very fact calls into question the extent to which Murks truly reflects a Dracula that might have been, but if we are seeing such a reflection here, then thereís one more parallel universe movie I really wish I could see. With his bushy eyebrows and bulbous forehead, Keith fits Bram Stokerís description of the character better than Lugosi or Christopher Lee ever did, and he can do perfectly credible hypno-eyes without any help at all from a guy with a pen light standing off-camera.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact