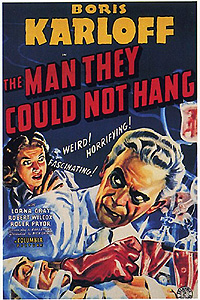

The Man They Could Not Hang (1939) **½

The Man They Could Not Hang (1939) **½

One of the neat things about Hollywood’s second period of infatuation with horror movies is that it brought out studios that hadn’t much participated in the first one. 20th Century Fox, RKO, Monogram, PRC— none of them had contributed at all sustainedly to the genre between 1931 and 1936, but all overcame their former reticence when the industry as a whole got back into the scare business in 1939. Columbia too discovered a new enthusiasm for horror, and to an even greater extent than was usual in those days of powerful studio heads with clear ideas of their companies’ brand identities, Columbia’s wartime horror pictures initially exhibited a distinct uniformity of subject matter and approach. While Universal concentrated on resurrecting their early-30’s monster menagerie, while Monogram concocted ever more ludicrous vehicles for Bela Lugosi, and while MGM tried so hard to stay classy that they almost forgot to scare anybody, Columbia elaborated the premise behind a minor British chiller called The Man Who Changed His Mind into a micro-genre all their own.

The common denominator in Columbia’s turn-of-the-40’s horror films— and in their apparent inspiration from across the Atlantic— is Boris Karloff playing a doctor driven to crime and madness by uncomprehending enemies interfering with his work. In The Man They Could Not Hang, the first of the cycle, the doctor is Henryk Savaard; the work is a process for inducing controlled, temporary death in surgical patients (Savaard will later liken it to turning off a motor to facilitate repairs); and the uncomprehending enemy is Savaard’s own nurse, Betty Crawford (Ann Doran, later of The Man Who Turned to Stone and It!: The Terror from Beyond Space). The point of contention between Crawford and her employer is Bob Roberts (Stanley Brown, who returned for Columbia’s next two mad doctor movies, The Man with Nine Lives and Before I Hang), Savaard’s grad-student assistant, who inconveniently is also Betty’s boyfriend. Bob himself has complete faith that Savaard’s resuscitation technique— which has thus far been consistently successful with experimental animals— will work just as well on a human subject, and he volunteers to be the first to undergo the process. Betty, however, can’t get past the part where Bob is going to be clinically dead, and she doesn’t believe for a moment that Savaard’s artificial heart (a rather more mad-sciencey version of the recently perfected Lindberg Heart) has the power to restart Bob’s own. When she can’t talk him out of being Savaard’s first human guinea pig, she rushes to the police station to tell Lieutenant Shane (Don Beddoe, from Night of the Hunter and The Boogie Man Will Get You) that the doctor is about to murder her boyfriend. Shane, a team of uniformed cops, and Stoddard (The Drums of Fu Manchu’s Joe De Stefani), the police department’s pet doctor, reach the Savaard mansion at exactly the worst time, however. Roberts has been dead for half an hour already, but Savaard and his other assistant, Lang (Byron Foulger, from The Devil’s Partner and The Magnetic Monster), have just begun prepping the resuscitation machine when the lieutenant and his men come knocking. Shane, hardly the most imaginative of men, sees only a dead body and the person who admits to doing the killing; he has very little interest in the doctor’s explanation of the experiment or his assertion that Roberts volunteered for his part in it. Betty, who knows perfectly well that Savaard is telling the truth on the latter point, says nothing at all about it. And Stoddard puts the finishing touch on the whole fiasco in defiance of Savaard’s pleading to be permitted to complete the experiment and rescue Roberts when he assures Shane that what the other doctor proposes to do is impossible. The one thing that does go Savaard’s way is Lang’s success in evading the notice of the police. Savaard sent him away through the lab’s back door as soon as he realized who was demanding admission to the house.

Dr. Savaard’s trial goes every bit as well as his remonstrance with Shane and Stoddard. The doctor plays right into the hands of District Attorney Drake (Scared Stiff’s Roger Pryor) when he takes the stand in his own defense, giving a bizarre and rambling speech that all but asks to be twisted into a Nazi-like “survival of the worthiest” manifesto. Judge Bowman (Charles Trowbridge, from The House of the Seven Gables and The Thirteenth Chair) oversees the trial with only the most thinly disguised favoritism toward the prosecution. And jury foreman Clifford Kearney (Dick Curtis) turns out to be a bullying blowhard who has little trouble browbeating even the most skeptical of his fellow jurors into casting their votes in favor not merely of Savaard’s guilt, but of his execution. It’s almost like something out of a pre-Code Warner Brothers crime melodrama. Even Savaard’s post-sentencing address to the court gets heard with the ears of preconceived notions, as his “You’ll all be sorry when you come down with life-threatening medical conditions from which my techniques could have saved your asses” is universally misinterpreted as a delusional death threat by the journalists reporting on the case. Again, Lang is Savaard’s one ray of sunshine, arriving at the prison a few days before his execution with forms providing for the donation of the doctor’s body to medical research. I bet you can guess which medical researcher is going to wind up with it, too, can’t you?

Sure enough, several members of Savaard’s jury turn up dead in the weeks following his execution, apparently by suicide. The pattern goes unnoticed, however, until “Scoop” Foley of the Tribune (Robert Wilcox, of The Mysterious Dr. Satan and the lesser-known film called The Unknown) realizes that he’s heard the name of the most recent “suicide” before somewhere. Foley was one of the reporters who covered the Savaard trial, and it doesn’t take him long to uncover the other deaths or to make the connection between them. Furthermore, following up with the other participants in the trial turns up the startling fact that Judge Bowman, D.A. Drake, Lieutenant Shane, Dr. Stoddard, and all but three of the surviving jurors have lately received letters or telegrams from Janet Savaard (Lorna Gray, from Valley of the Zombies and Perils of Nyoka), the dead doctor’s daughter, inviting them to her father’s mansion on some mysterious, urgent business. What makes this startling— as opposed to merely suspicious— is that Foley is dating Janet (the pair having become very close during the trial), and he never heard about any such plans. Neither, or so she claims, has Janet. The obvious implication is that whoever has been pursuing this stealthy vendetta against Savaard’s “killers” has decided to pick up the pace and eliminate the bulk of the remaining potential targets in a single fell swoop, and it’s too late at this point for Foley or Janet to do anything to warn the invitees of their peril except to go to the mansion themselves. And equally obvious, were any of the victims-to-be imaginative enough to see it, is the implication that their foe is Savaard himself, restored from the gallows by the very process that he was executed for attempting to test on Bob Roberts. Of course, if any of them had it in them to see that coming, they probably wouldn’t be in their present fix in the first place…

The Man They Could Not Hang’s paucity of ambition is nowhere more evident than in its third-act transformation into a modernized spooky house flick. It isn’t even a very clever or well thought-out modernization, either, for screenwriter Karl Brown never presents a remotely plausible reason for Savaard’s guests to place themselves in his hands. It isn’t for nothing, after all, that the reading of a will became such a durable genre cliché. Perhaps people really were that much more trusting in 1939, but I find it impossible to credit the notion that all of these folks would unquestioningly comply with an unexpected summons from a nearly complete stranger, with whom their only connection is that they were instrumental in getting her father hanged. You’d think at least one of them would have pulled out the phone book and given Janet a call to ask just what this cryptic telegram was supposed to be about. The film also suffers from a serious lack of clarity concerning the personality of Dr. Savaard, whose essential good-heartedness comes and goes in a way that looks less like deliberate ambivalence than incoherence in the service of plot convenience.

Still, The Man They Could Not Hang gets a fair amount of stuff right, too. The vague characterization of Henryk Savaard wouldn’t matter so much, for example, were it not for the strength of the scenario put forth in the first act. Savaard’s process does work; its potential value to medicine is obvious; the doctor was railroaded to the gallows; Betty Crawford does deserve the lion’s share of the blame for her boyfriend’s death. The Man They Could Not Hang thus offers us a villain who, up until the moment he sets out to commit mass murder, is entirely in the right, making itself about as thoroughgoing a subversion of the thinking behind the Hays Code as could be contrived while abiding by the letter of its strictures. The movie also earns distinction by featuring a reporter hero conspicuously outside the tradition of Lee Tracy’s Doctor X role, and an extraordinarily activist and effectual heroine in the seemingly unlikely form of Janet Savaard. So although this film neither lives up to its full potential nor rises above its station as a quickie programmer, I can nevertheless see why Columbia would be tempted to revisit the concept behind it three more times (or four, if you count the overtly self-parodying The Boogie Man Will Get You) in the years to come.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact