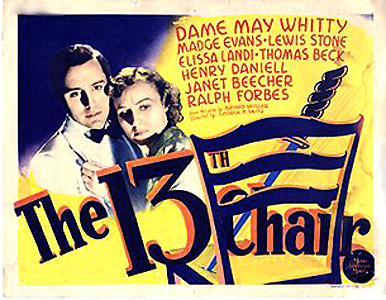

The Thirteenth Chair (1937) **½

The Thirteenth Chair (1937) **½

By 1936, horror movies had been big business for several years, and while the number of such films released that year does suggest a decline in audience interest since the fright flood of 1932 and 1933, it’s equally plain that there was still a fair amount of money to be made by peddling vampires, voodoo, and mad science. And yet the ghost train nevertheless came screeching to a halt in 1937; pressure groups outside the Hollywood industry were primarily to blame. The British Board of Film Censors issued a general interdict against horror films that year, depriving the studios of what had been up ‘til then a lucrative secondary market. Meanwhile back home, finger-wagging media editorialists and outfits like the Legion of Decency were making more noise than ever, incensed that movies like The Raven and Mad Love could still get made even despite the tightening of censorship guidelines in 1934. But while horror, strictly construed, vanished from the studio production schedules until 1939, 1937 and 1938 saw a curious revival of what might be called “surrogate horror.” Spooky house mysteries and sham séances made a noticeable comeback, and there was a miniature boom in movies like The Invisible Menace, a pedestrian detective programmer featuring Boris Karloff as the prime suspect, whose casting conspired with the lurid title to suggest a film far more interesting than what actually appeared on the screen. If ever there was a right time to remake The Thirteenth Chair, 1937 was it.

The most immediately obvious difference between this version of The Thirteenth Chair and the one from 1929 is how much less stagebound the newer one is. First we get an establishing shot of a Calcutta street scene, then we’re following Scotland Yard detective Inspector Marney (Lewis Stone, from The Phantom of Paris and The Lost World) as he meets with Police Commissioner Grimshaw (Matthew Boulton, of The Woman in White and The Brighton Strangler) to discuss the murder of Leland Lee. Lee was not a popular man— in fact, he seems to have been hated by everyone he knew save John Wales (Henry Daniell, from The Body Snatcher and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea)— but he had connections to lots of people closely tied to Governor Sir Roscoe Crosby (Daughter of the Dragon’s Holmes Herbert, who had played the same role in 1929). Consequently, Grimshaw feels his hands are tied, and that’s why he has called on Marney to take over the case. (Cops from the mother country, presumably, are a lot more impressive than those who spend their careers in the colonies.) Lee had been stabbed in the back in the parlor of his home, apparently while preparing to serve tea to a guest. There are eyewitness reports of a woman leaving the house shortly after the crime was probably committed, but she was heavily veiled, and nobody who saw her could identify her. But as Marney and Grimshaw are soon to learn, Wales thinks he knows who the mystery woman was. The dead man’s sole friend is already in Lee’s house when the two policemen arrive to acquaint Marney with the crime scene, having let himself in with the key Lee once gave him, and he presents Marney and Grimshaw with the outline of an incredibly screwy plan to bring the killer out into the open by means of a fraudulent séance. All he needs to make it work is for Grimshaw to talk Sir Roscoe into throwing a party at his house, with a guest list dictated by Wales.

Don’t ask me why, but Crosby goes for it. In addition to himself, his wife (Janet Beecher), his son, Dick (Thomas Beck), and his daughter, Helen (Elissa Landi), there are to be nine guests. Wales will be there, of course, as will Helen’s husband, Lionel Trent (Ralph Forbes, from the 1939 versions of Tower of London and The Hound of the Baskervilles). So will Helen— but call her Nell— O’Neil (Transatlantic Tunnel’s Madge Evans), who is both Lady Crosby’s secretary and Dick Crosby’s fiancee. Also in attendance will be Mary Eastwood (Heather Thatcher, of Gaslight and The Undying Monster) and Dr. Mason (Charles Trowbridge, from Valley of the Zombies and The Mummy’s Hand), both of whom were acquainted with Leland Lee. In fact, all of the aforementioned people had crossed paths with the deceased at some point or other, and most of them did so on terms that could easily be construed to provide a motive for murder. Then there are Professor Feringeea (Lal Chand Mehra, from Drums of Fu Manchu and The Monkey’s Paw… and would you look at that— it’s an Indian being played by an Indian in a 1930’s Hollywood second feature!), Mr. Stanby (Theater of Blood’s Robert Coote), and the second man’s flighty sister, Grace (Elsa Buchanan). They’ve been invited expressly for the sake of distracting the other guests from the real purpose of Sir Roscoe’s party, as all of them are seemingly beyond suspicion in Lee’s death. Finally, there’s Madame Rosalie LaGrange (Dame May Whitty, of Flesh and Fantasy, identified in the credits as “Distinguished English Actress Dame May Whitty”— aren’t you impressed?), who will conduct the séance. Madame LaGrange happily concedes that most of her communications with the spirit world are unadulterated bullshit, but she also assures the Crosbys and their guests that her powers are real, and promises that any messages conveyed from the other side tonight will be the genuine article.

Madame LaGrange is lying, however. The whole conversation between the medium and her “spirit guide” has been scripted in advance by John Wales. She’s supposed to put the guests in touch with the spirit of Leland Lee, who will give the name of the woman Wales suspects as Lee’s killer— naturally herself a participant in the séance— on the theory that this will panic her into confessing to the crime. Instead, with everyone seated in a circle, their hands linked, the lights turned out, and the door to the parlor locked from the outside, somebody stabs Wales just as the séance was getting to the good part. This brings Marney, Grimshaw, and a small army of uniformed police to the governor’s mansion, to which everyone is to be confined until Marney can get to the bottom of things. The link between the new murder and that of Leland Lee is obvious enough, but there are plenty of plausible suspects in the room. Lee ruined Dr. Mason’s career back in Britain, broke up Mary Eastwood’s marriage, and seems to have conducted an affair with Helen Trent either before or during her marriage to Lionel. Even Professor Feringeea, who seems to have a pretty good alibi for the night of Lee’s murder, had plenty of reason to want him dead, for Lee was blackmailing the professor with the knowledge that he had done prison time for forgery before moving back to Calcutta from London. But the strongest circumstantial case of all is that incriminating Helen O’Neil. She bears the name Wales had meant for Madame LaGrange to speak from her “trance,” she was sitting beside Wales when he was killed, and Marney traps her into admitting that she visited Lee on the day of his murder. And perhaps most damningly, the medium— who turns out to be Nell’s mother— is pretty obviously trying to get in the way of Marney’s investigation. The only thing keeping it from being an open-and-shut case is that the other Helen had been sitting on John’s other side when he was stabbed. Given that she had her own reasons for wanting Leland Lee gone, that introduces just enough uncertainty for Marney to let Madame LaGrange persuade him to contrive a second séance, this time with Wales as the stool pigeon from beyond the grave.

The 1937 version of The Thirteenth Chair is a much more accomplished film than its predecessor, and only part of the difference can be attributed to advances in filmmaking (or sound-recording) technique and technology during the intervening eight years. The remake is better paced, more thoughtfully constructed, and far better acted all around than Tod Browning’s version. And more importantly, although the central conceit of the C.I.D. cooperating with not one but two cockamamie schemes to catch a killer with a phony séance remains as stupid as ever, the remake features a totally different solution to the mystery— one which requires neither the final-scene revelation of a previously unsuspected motive, nor an audience willing to ignore the physical circumstances under which Wales was killed. It may not have the “before they were stars” appeal of a pre-Dracula Bela Lugosi, and it certainly isn’t anything worth getting excited about, but this Thirteenth Chair is still a big step up from what came before it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact