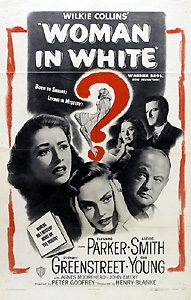

The Woman in White (1948) **½

The Woman in White (1948) **½

Wilkie Collins’s novel, The Woman in White, was published sometime in the 1860’s, when Gothic fiction was at the height of its popularity. It itself was quite a big hit, and it quickly became one of those works which the movie industry simply would not leave alone during its formative years. There were three or four silent versions made in the United States, plus a couple of British-produced talkies released by the early 1940’s. (For that matter, there were also two made-for-TV versions and one movie each from Russia and Sweden in later years.) But the best remembered interpretation is the one that Warner Brothers put out in 1948. This pattern makes a lot of sense when you really think about it. The pure Gothic was still alive and well as a literary form in the teens and 20’s, though it had started to lose ground to the newer pulp genres, and a classic of its type like The Woman in White would have been an obvious choice of subject matter for a film during the silent era. Meanwhile, in 30’s and 40’s Britain, something like The Woman in White— which skates right up to the edge of what would now be considered the horror genre without ever quite crossing over that admittedly rather vague boundary— would have seemed like a perfect means for satisfying the public’s newly developed craving for fright films without flirting too openly with the wrath of the Board of Film Censors, which could be counted upon to ban even such innocuous movies as Tod Browning’s Dracula. Later still, after the bottom dropped out of the Hollywood horror market in 1946, a studio might turn out a film like the Warner The Woman in White as a way to test the waters or to keep filmmakers with a penchant for the macabre working without taking the risk of producing a flat-out horror flick. Though its faithfulness to its direct inspiration is debatable, this version of The Woman in White is certainly a faithful screen rendering of what made the Gothic genre as a whole tick. Its somewhat action-starved script is positively bursting with such genre commonplaces as evil, scheming noblemen, beautiful, endangered women, somber castles, sinister madhouses, scandalous secrets, and nefarious plans of such Byzantine complexity that they could never possibly come close to working in the real world. And while I’m not sure I’d actually give it my recommendation, it certainly kept me entertained— at least once its listless, meandering first act finally wrapped itself up.

Walter Hartright (Gig Young, from the 1961 TV remake of The Spiral Staircase) arrives in the middle of the night in the small English village of Limmeridge, and having missed the last coach to the castle of Count Frederick Fairlie (John Abbott, of The Vampire’s Ghost and Cry of the Werewolf), gets directions from the baggage handler at the railroad station and continues on to his destination on foot. While he is walking a lonely stretch of road through a dense forest, he encounters a young woman dressed entirely in white (Eleanor Parker, from The Naked Jungle and Eye of the Cat), who talks to him just long enough to convey the suggestion that she’s completely out of her mind before she is frightened off by the approach of a carriage down the path. The driver of the carriage asks Hartright if he has, by any chance, seen a white-clad woman during the course of his trip; someone meeting that description escaped recently from the private insane asylum in nearby Newbury. Something about the carriage and its occupants strikes Hartright as suspicious, though, and he feigns ignorance on the subject of escaped madwomen. The carriage rolls off down the road, and Hartright resumes his journey.

The reason Walter Hartright is on his way to see Count Fairlie at Limmeridge House is that the count has hired him to serve as an art teacher for one of his nieces; evidently, Hartright is a painter of some renown. The artist’s first impressions of the castle and its denizens are predictably disconcerting. Niece Marian Halcombe (Alexis Smith, from The Smiling Ghost and The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane)— not the one Hartright is here to teach— seems decent enough, but her uncle the count could best be described as Poe’s Roderick Usher exaggerated to the point of parody. He has one of those ever-popular nervous afflictions that render his senses so acute that any but the dimmest light and quietest sounds are intolerable to him, and he protests constantly that his health would be wrecked by any sort of excitement. Fairlie also has a houseguest, longtime family friend Count Alessandro Fosco (Sydney Greenstreet), whom Hartright recognizes as one of the men inside the coach he encountered on the road a little while ago. This revelation is made doubly suspicious by the fact that Fosco makes a point of questioning him once again about the woman in white the moment Marian is out of earshot.

As for the mysterious woman, she becomes even more so the next morning, when Hartright discovers that she has a double. Fairlie’s other niece, Lauren (also Eleanor Parker)— this is the one he’s supposed to be teaching— looks so much like the woman in white that Hartright initially mistakes the girl for her. The subject comes up over breakfast, and Count Fosco seems inordinately perturbed when he hears Lauren blabbing about what her teacher saw on the road last night. An old maid’s reminiscence about a girl very similar to Lauren who lived briefly at the castle when Lauren was perhaps eight years old makes Walter even more curious. It has the same effect on Marian, too, for that matter, and she spends most of the following afternoon looking over her mother’s correspondence with Count Fairlie’s late wife, searching for any mention of such a child. Eventually, she turns up a letter in which her mother describes a girl named Ann Catherick, who seems a plausible match for both the child mentioned by the maid and the white-garbed woman Hartright met in the woods. But neither Marian nor Walter has much chance to study this letter, because it swiftly disappears into the possession of Count Fosco. I’m telling you, that man is no good.

He’s not the only one, either. As soon as he has satisfied himself that Lauren’s double is hiding on or about the castle grounds, Fosco barges in on his host and begins a heated discussion regarding what is to be done about her. Most worrisome is the two counts’ talk of a man named Sir Perceval Glyde, whom Fairlie suggests as the best man to take care of the situation before Fosco dismisses Glyde on the grounds that his only solution to everything is violence. Well as it happens, Sir Perceval (John Emery, from Kronos and The Mad Magician) ends up on the scene anyway. He arrives at Limmeridge House the next day, occasioning the revelation of yet another layer to the intricate intrigue surrounding the Fairlie family— he’s engaged to marry Lauren! Hartright is not at all happy to learn of this, as he and his pupil have fallen in love with one another, and the girl never said anything about having a fiance. Truth be told, Lauren isn’t exactly thrilled to see Sir Perceval, either, especially once she tells him she’s in love with another man and he still insists upon marrying her as soon as possible. Then Hartright has another run-in with Ann Catherick out in the garden, and learns that the situation is even worse than it appears. If Ann is to be believed, Lauren’s engagement to Sir Perceval was engineered by Count Fosco as a means of separating Fairlie from his family fortune; the marriage settlement stipulates that Glyde will inherit everything in the event that something should happen to Lauren, and one assumes that Fosco would also receive a little something as a reward for brokering the deal. Meanwhile, Ann herself has been languishing in Count Fosco’s Bedlam-like private madhouse, where she can be kept from upending the whole scheme by revealing what she knows. Seeking to protect Lauren, Hartright convinces Ann to come with him to confront the plotters, but Ann chickens out when she sees Fosco, and runs off into the night before he spots her in return. This, alas, leaves Hartright rather less convincing than he might have been, and he ends up leaving Limmeridge House in disgrace while the marriage goes ahead according to plan.

And here, finally, is where the real meat of the story is to be found. Marian gradually comes to realize what evil men Glyde and Fosco are, while Lauren herself lives to regret her refusal to believe Hartright’s accusations even more strongly than her cousin. And on top of everything else, Sir Perceval grows impatient to take possession of the Fairlie fortune, even if that means killing his new wife. Fosco, as usual, has something rather subtler in mind, a plan predicated upon the existence of a woman all but indistinguishable from Lauren. All he needs to do is get his hands on her...

The biggest obstacle standing between you and enjoyment of The Woman in White is the first half of the movie. For some 50 minutes, people talk, and they talk, and they talk. They give each other long and searching looks, pregnant with sinister meaning. They follow each other around Limmeridge House and its grounds, spying on one another through windows and telescopes and closed doors. What they do not do is move the plot along. In this case, though, all this inaction is both understandable and forgivable because so complex a scheme as Fosco and his co-conspirators have evolved takes time to set up, especially if you want to do so in a way that generates suspense or at least some sense of mystery. And really, it’s worth the wait just to watch Sydney Greenstreet in action once Lauren is safely married off and Fosco no longer has to pretend not to be a cold-blooded, conniving bastard. Then again, it must also be said that the ending absolutely blows— way too pat and tidy considering what comes before it. So I guess the question for you is, does the idea of watching a movie for the middle seem too bizarre to bother with?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact