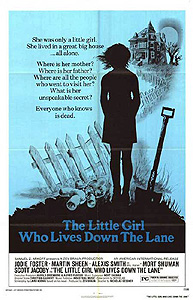

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (1976) *****

The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane (1976) *****

The nature-vs.-nurture debate is probably the oldest and most fundamental in all of behavioral psychology— so old and so fundamental that the Jews tried to come to grips with it in their very creation myth. There have been plenty of swings of the pendulum since then, but the truth is that we very likely aren’t a whole lot closer than we ever were to determining the exact proportions in which innate and contingent factors combine to shape the human psyche. In the mid-1950’s, when the “nature” side of the argument still had the upper hand even despite the recent exposure of the ghastliness such thinking can lead to when taken to extremes, the concept of intrinsic disposition toward evil combined with paranoia over the rapidly widening cultural schism between parents and their children to produce The Bad Seed. Twenty years later, the “nurture” party was in the ascendant, and one of the things popular culture got out of the deal was another movie about an extremely dangerous young blonde girl, one that took exactly the opposite tack from the earlier film. Rhoda Penmark was born evil, but the titular Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane is very much a product of her environment. What’s more, as befits the era’s greater tolerance for unconventional lifestyles, the movie is careful to pass no judgement upon her, and to give the audience everything they could possibly need to understand her side of the story. William March handed down his verdict on Rhoda right there in the title, but writer Laird Koenig and director Nicholas Gessner take a much less leading approach to her 70’s counterpart. That said, though, the people who make Rynn Jacobs feel threatened tend to end up just as dead as the ones who crossed Rhoda Penmark.

When we first meet Rynn (Jodie Foster, from Taxi Driver and The Silence of the Lambs), the daughter of globe-trotting Jewish poet Lester Jacobs, she’s lighting the candles on her thirteenth birthday cake. It isn’t a birthday party in the generally accepted sense, though, because so far as we can see, she’s the only person in the house. There’s a knock at the door, and Rynn does a very strange thing— she grabs a pack of cigarettes from the mantlepiece, lights one, and puffs on it frantically for a few moments before stubbing it out and rushing off to answer the knock. The man on the front porch is Frank Hallet (Martin Sheen, of The Dead Zone and The Final Countdown), who we will later learn to be the son of Cora Hallet (Alexis Smith, from The Smiling Ghost and The Woman in White), the real estate agent through whom Jacobs arranged the three-year lease on the house. It’s Halloween as well as Rynn’s birthday, and Hallet is taking his two sons trick-or-treating. Oddly, however, Hallet has hurried so far ahead of the boys that there’s absolutely no sign of them around. Not much time passes before Frank starts giving off signs as to why— he’s a great admirer of very young girls (even Kip Winger would consider this guy a sleazy creep), and while he claims to have something to discuss with Rynn’s father, he seems most unwilling to let her go summon him. In fact, the moment Rynn makes a decisive move in that direction (immediately after Frank touches her in a manner that couldn’t possibly be spun as in any way appropriate), Hallet takes to his heels, intercepts his sons (who are only just now approaching the Jacobs house), and leads them off someplace else.

The thing is, though, that Rynn’s comportment both during and before Hallet’s visit has me thinking that Lester wasn’t really in the house that night. In fact, I’ve got a sneaking suspicion that Rynn actually lives there all by herself. She never goes to school, although she studies quite diligently on her own at home. She seems to finance her day-to-day existence by means of a thick sheaf of traveler’s checks stored in a safe-deposit box at the local bank, held jointly in her and Lester’s names. And perhaps most tellingly, not only is the lease on the house good for three years, but it’s all been paid for up front. Also, Lester seems invariably to be indisposed when an adult comes by for whatever reason; Rynn says he’s sleeping, or he’s in the study immersed in his work, or he’s meeting with his publisher in New York. Incidentally, people in this town sure are a bunch of busybodies, too! The bank tellers, the librarian, and even Ron Miglioriti, the affable village cop (Mort Shuman) can’t seem to spend 45 seconds around Rynn without asking after her dad. The most troublesome villager, though, is Cora Hallet. She’s a close friend of the people who own the Jacobses’ house, and she’s also a pushy, arrogant bitch— and a bigot, to boot. On Friday, November 1st, Mrs. Hallet comes over to plunder the Jacobses’ crabapple trees, and to collect the jelly jars the landlords store in the cellar. Evidently the autumn jelly-making is a long-established tradition with Cora and her friends, and she reckons herself perfectly within her rights to just barge right in on the new tenants and help herself. Queen Wasp even starts shifting the living room furniture back into the arrangement that prevailed when the owners lived there! Rynn is understandably irritated at Mrs. Hallet’s presumption, and the tone of the conversation rapidly turns adversarial. The snapping point comes when Cora begins asking questions about her son’s visit the night before. She knows all about Frank’s proclivities, and she’s clearly concerned about how well he behaved himself. Of course, it’s equally plain that Mrs. Hallet doesn’t really give a shit about Rynn’s well-being, but seeks only to make sure her reprobate spawn stays out of trouble with the law. The increasingly unsociable social call ends with Rynn throwing Cora out of the house, and Cora talking darkly about how interested her buddies on the school board are going to be when they hear about this little girl who sits at home listening to “Teach Yourself Hebrew” records on weekday mornings, when she ought to be in class.

Cora and Rynn’s next meeting is even more hostile. Mrs. Hallet makes another bid to get her precious jelly jars, but her real objective is obviously to use her position as a friend of the landlords to bully Rynn and her father into keeping quiet about Frank’s continuing and increasingly sinister interest in the girl. Rynn refuses to be intimidated, however, and in order to make herself feel as though she has not been completely thwarted, Cora bulls her way down to the cellar to get the seals to the jelly jars, which Rynn neglected to bring up when she retrieved the jars themselves. We don’t get to see what Cora finds down there, but I think we all have at least a general idea what it is that makes her scream at the top of her lungs and flee upstairs in such a hurry that she knocks over the support rod for the cellar trapdoor, bringing it smashing down onto her head.

Now Rynn has a huge problem. The new corpse in the cellar is a pillar of the community, and not just (to take a wild guess) some big-city Jew who only moved into town a couple of months ago, and furthermore, that corpse’s instantly recognizable vintage Bentley is now sitting out in the driveway where anyone passing by could see it. Rynn doesn’t really know how to start a car, let alone drive one, so disposing of the evidence is going to be quite a challenge. That’s when Mario Podesta (Scott Jacoby, of Bad Ronald and To Die For) rides by on his bicycle. Mario hears Rynn wrestling with the Bentley’s ignition, and he comes up the drive to see if he can help. It’s an odd scene to say the least. Here’s this gimp-legged high school boy, dressed up for the magic show he was on his way to perform at “some rich kid’s birthday party,” confronting a girl who is visibly much too young to drive over a car they both know perfectly well does not belong to her. And because Mario’s father owns the local service station, he’s able to see right through what might otherwise have been a plausible lie about Mrs. Hallet having entrusted her father to take the Bentley to the shop before he was unexpectedly called away on business. But rather than dropping the dime on Rynn, Mario returns after his magic act, and bails her out of trouble by driving Cora’s car back to her real estate office, where she usually keeps it.

So begins a very strange and much embattled teenage romance. Mario turns out to be Officer Miglioriti’s nephew, and between his covering for Rynn when “Uncle Ron” comes by to ask if either she or her dad has seen Cora Hallet lately and his defending her— as in physically, with a sword-cane— when Frank Hallet makes a substantially more frightening attempt to get the same information, he earns enough of the girl’s trust to be let in on a few of her secrets. Secrets like what Cora’s Bentley was really doing sitting unattended in Rynn’s driveway. Secrets like what became of her missing father, who turns out to have drowned himself in Long Island Sound after being diagnosed with inoperable cancer and making all of the sneaky arrangements whereby Rynn now lives, leaving her with an admonition to do whatever she has to in order to survive on her own. Secrets like how her mother, who tried to reclaim her two months ago despite having abandoned her and her father a decade before, wound up dead and mummified in the cellar. Mario more than vindicates that trust, too. Not only does he agree to keep Rynn’s secrets as if they were his own, but he makes them his own by helping her dispose of the bodies permanently. Alas, he does so by burying them in the middle of a winter downpour, contracting a life-threatening case of pneumonia for his troubles. That’s a plenty serious development in and of itself, but it also incidentally means that Rynn will be left to her own devices the next time Frank Hallet sets his sights on her.

As the foregoing should indicate, The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane is not exactly the straightforward horror movie that its premise (to say nothing of its advertising campaign) would normally imply. Rather, it is more a drastically bent coming-of-age love story, something like a Bridge to Terabithia in which the secret world the girl opens up involves not imagined adventures in a fairy-tale kingdom, but all-too-real poisoning, pederasty, and blackmail. What horror there is (and there’s plenty of it, to be sure) derives less from Rynn’s actions, however deadly they may be, than from those of the adults whom she must constantly outmaneuver simply in order to maintain some modicum of control over her life. Earlier on, I compared The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane to The Bad Seed, but the crucial difference is that this movie tells the story from the killer child’s point of view. Unlike Rhoda, Rynn seems to have the filmmakers’ sympathies (if not necessarily their approval), and she is given a chance to earn ours as well. She can be disturbingly ruthless (the scene in which Rynn tells Mario how she dispatched her mother plays up this point beautifully, simultaneously making a joke out of it and emphasizing how very far from funny it is), but she is not without loyalty, empathy, or love for all that. And, of course, the Hallets are so despicable that it would be hard not to root for Rynn against them even if she were as much of an asp as the Penmark girl— no fate is too awful for a man who’ll torture a hamster with a lit cigarette in order to make a point. Nevertheless, Rynn is the central figure here, and the character’s credibility is the key factor in the credibility of the film as a whole. As would so often be the case in her subsequent career, Jodie Foster’s performance is therefore the element on which The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane stakes the bulk of its success, and she rises to the challenge just as she generally does today. Rynn Jacobs, in all her eerie calm and harried loneliness, is as real, as living, as any movie character you could name. The big difference, obviously, between this performance and any of Foster’s better-known roles from the last two decades is that the Foster we see here is just thirteen years old. Granted, she did not lack for experience even at that age, having been a fixture of TV commercials and children’s fare since practically the day she was born. But in 1976, she was preparing to leave that familiar territory, taking her first transitional steps toward an adult acting career. That, I think, is the single most fascinating aspect of this film. Together with Taxi Driver, it shows the initial stage of an almost unprecedented transformation, as a seemingly ordinary, minor child star evolves into one of the most brilliant actresses of her generation. Foster herself reputedly does not care much for The Little Girl Who Lives Down the Lane, or for her performance in it, but so far as I can see, she is merely demonstrating the oft-noted principle that an artist is frequently her own harshest critic.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact