Gaslight/Murder on Thornton Square (1944) ***½

Gaslight/Murder on Thornton Square (1944) ***½

As any dimly perceptive observer will surely have noticed, the past few years have seen a considerable number of Hollywood movies that are remakes of successful foreign films, many of them only a few years old. Most conspicuously, there has been the recent trend for remaking buzz-generating Asian horror films rather than simply dubbing and importing the originals; The Ring, The Grudge, and Dark Water are all high-profile examples. But while it may be true that there’s more of that sort of thing going on today than was the case in the past, the practice itself is much older than is generally recognized. In fact, one of the most highly respected American suspense movies of the 1940’s was remade from an English film that was released only four years previously, and the process that led to its existence involved behavior so underhanded on the part of the studio heads that it might actually prove illegal to attempt comparable chicanery today.

When the British stage play Gaslight was brought to the United States under the title Angel Street early in 1939, it was a big and long-lasting money-maker. When it reached Broadway, for example, it ended up staying for nearly three years. Columbia swiftly acquired the rights to mount a film version, but that studio’s leadership dawdled for long enough that a thicket of complications sprang up around them. Unaffected by the screen-rights situation in America, British National produced their own Gaslight movie in 1940, before anyone at Columbia had done anything more than throw ideas around. The movie did about as well in its home country as Angel Street was doing on stage over here, and Columbia was faced with a quandary— should they go ahead and make their film, or should they simply hammer out a distribution deal with British National, and reap the benefits of holding the film rights without having to do any real work? The question was made more difficult by the fact that the British film contained a fair amount of material which was apt to give the Production Code Administration a conniption fit, and after hemming and hawing for a couple of years, the Columbia bosses essentially decided not to decide. They sold the US film rights to Gaslight to MGM instead. MGM’s leadership was much more decisive than Columbia’s, and the former studio moved fast to get an American Gaslight into the theaters. But by that time, there were a number of copies of the British National Gaslight already in circulation in the States, although they were receiving only relatively narrow distribution (probably because of the murky legal circumstances). This is where the dirty dealing comes in. As they had done in 1941 with their version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, MGM were looking to remake another studio’s movie, and this time, there would be a mere four years separating the new version from the old; because re-releases were extremely common in those pre-television days, there was every reason to fear the possibility of the British National Gaslight coming into direct competition with the forthcoming remake. Thus it was that MGM cut a deal with British National superceding any and all arrangements which had previously been made for distributing the 1940 Gaslight in the US. Not only would British National refrain from circulating their movie in this country any longer, but MGM would be empowered to round up all prints and negatives of the 1940 version and destroy them! What made the English studio agree to such an scheme is totally beyond me, but the deal came very close to erasing a true triumph of suspense cinema from the world. Luckily, a few copies of the film escaped, and the original Gaslight resurfaced in the early 1950’s. Of course, by that point, the MGM version had so totally supplanted its predecessor in the public eye that the American studio basically got what it wanted anyway, the diminution of a feared competitor to the status of historical footnote.

What makes the shenanigans accompanying the release of MGM’s Gaslight all the more offensive is that they were hardly necessary to cover the studio’s ass; the remake is quite strong enough on its merits to hold its own against the earlier version, even if it comes up somewhat short in a number of important respects. It begins by making its most conspicuous divergence from the plot of the original, picking up with the immediate aftermath of the murder of internationally renowned Swedish opera singer Alice Alquist at her home on Thornton Square, rather than with the killing itself. Alice had no children of her own, but at the time of her death, she was raising her teenage niece, Paula, whose parents both died before the girl was even out of diapers. With no other family to turn to, Paula gets shipped off to Italy, where she stays with an old friend of her aunt’s, singing instructor Maestro Mario Guardi (Emil Rameau).

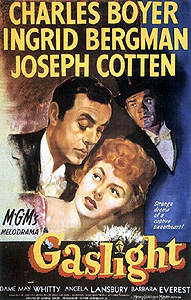

Ten years pass, and Paula grows up to be Ingrid Bergman, from the MGM Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. When we see her next, she is enduring Guardi’s chiding about how her mind never seems to be truly on her singing anymore. This, as Guardi soon guesses, is because Paula has fallen in love. Two weeks ago, she met a man from Prague, a pianist named Gregory Anton (Charles Boyer), and what began as a similarity of interests soon exploded into an all-consuming passion. Anton wants to marry Paula at once, but that’s a bit more drastic a step than she is ready to take just yet. Paula tells him instead that she is going to take a week’s vacation by herself in the lake country, so that she can think the prospect over in peace and seclusion. Gregory scuttles her plan by surreptitiously zipping out to the lake country himself and fixing it so that he’s there in time to meet Paula at the train station when she arrives, but Paula is more than happy to see him— especially after spending most of the ride out trapped in conversation with Mrs. Thwaite (Dame May Whitty, from Flesh and Fantasy and the 1937 remake of The Thirteenth Chair), a ghoulish old lady who coincidentally moved to Thornton Square the year after Alice Alquist’s murder, and who insisted upon regaling the horrified Paula with as many details of the crime as she had been able to dig up, blithely unaware that she was talking to the victim’s niece. Paula’s intended week of contemplation quickly morphs into the beginning of her honeymoon with Gregory Anton.

Now that the couple are married, the question arises of where exactly they’re going to settle down. Between the two of them, there’s enough money that they can pretty much take their pick, but Gregory mentions to Paula that he’s always fantasized about a house on a square somewhere in London. Paula, of course, happens to own just such a place, the house on Thornton Square which was left to her by her murdered aunt, but which she has hitherto considered to be too densely packed with hideous memories ever to be suitable as a primary residence. Now that she has Gregory in her life, however, Paula is willing to reevaluate the prospect of living on Thornton Square again. It doesn’t take her very long to decide that her new husband brings so much happiness into her life that she can face the old house once more.

From this point, the 1944 Gaslight comes to resemble the 1940 version much more closely. Among Alice Alquist’s personal effects is a letter from a man named Sergius Bauer dated two days before her death, the discovery of which agitates Gregory greatly for reasons he seems unable to explain. From the moment that letter turns up, the relationship between the Antons starts to change— and sharply for the worse, so far as Paula is concerned. Gregory becomes cruel and controlling, effectively keeping his wife a prisoner in her own home and skillfully using the household servants, Elizabeth (Barbara Everest, from The Uninvited and the first talkie version of The Lodger) and Nancy (Angela Lansbury, from The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Company of Wolves), as agents against her. Paula, too, changes after finding the letter from Bauer to her aunt. She grows increasingly emotional, indecisive, and high-strung, and begins losing and forgetting things constantly. Finally, it seems as though Paula may actually be losing her mind. Whenever her husband is out of the house (and he spends nearly all of his evenings out of the house these days), she hears noises from the boarded-up attic above her bedroom, noises which suggest that somebody is up there prowling around and moving stuff about. And when her husband is at home, things have a way of going missing under circumstances which imply that Paula has been taking them, hiding them, and forgetting all about it afterwards. In point of fact, though, there’s nothing at all the matter with Paula’s mind— or at least there isn’t yet. What’s really going on is that Gregory himself is engineering his wife’s apparent madness in order to get her out of the way so that he can search the attic without having to sneak around the way he does at present. You see, Gregory Anton is really Sergius Bauer. He used to play for Alice Alquist, and it was he who murdered her for the set of priceless jewels that were given to her by one of the crowned heads of Europe. Bauer was unable to search the house on Thornton Square thoroughly ten years ago, for he was forced to flee when the teenaged Paula awoke and came to investigate the sounds he was making as he ransacked Alice’s music room. A decade later, Bauer tracked Paula down and courted her under an assumed name, all in order to gain access to the house where he had committed his crime, and where he was certain the jewels could still be found. The trouble, from Bauer/Anton’s perspective, is that a little boy who was an ardent fan of Alquist’s back in the day has now grown up to be a police inspector (Joseph Cotten, of Baron Blood and From the Earth to the Moon), and he has been paying very close attention to the goings on at 9 Thornton Square ever since the Antons moved in. He knows the man of the house is up to something, and he has a hunch that that something is tied in somehow or other with the unsolved murder of Alice Alquist.

Gaslight is one of the classic suspense movies of the 1940’s, no two ways about it. It features beautiful cinematography, opulent production design, a strong script, taut direction, and superb performances from both Ingrid Bergman and Charles Boyer. Indeed, Boyer is very nearly the equal of Anton Walbrook in the British version, and Bergman outshines Diana Wynyard— as impressive as Wynyard had been— the way a floodlight outshines a candle. Unfortunately, this Gaslight is much more conventionally handled than its predecessor, and is marred in places by a few of the usual annoying MGM-isms. The comic relief from nosy old Mrs. Thwaite across the street, for example, never fails to bring the movie to a screeching halt, and the combination of the studio’s natural primness and the strictures of the Production Code meant that the US version would be missing such striking features of the original as the affair between Paul Mallen (as the Gregory Anton character was called in 1940) and the chambermaid or the gripping section of the conclusion in which it briefly seems as though Bella (as Paula was called) is going to take matters out of official hands by murdering her defeated tormentor before the police can arrive to take him into custody. I liked the heroine’s rescuer much better when he was a grizzled old tough guy instead of a young and handsome Hollywood Leading Mantm. I also greatly prefer the 1940 version’s immediate openness about the husband’s villainy, and I found it much more convincing to portray the heroine from the start as a weak woman with a history of mental illness. Bergman does great things with Paula Anton as both the free spirit she is when we meet her and the emotional cripple she later becomes, but even she can’t quite manage to sell the transition between the two states. Finally, the Hollywood Gaslight suffers a bit from its reliance upon exactly the kind of contrivances and coincidences which the British version eschewed. In 1940, it was the Gregory Anton character who was related to the murdered rich woman, and he married the Paula character not because she was the one person in the world who could get him back inside the scene of his unfinished crime, but simply because she had enough money to cover the rent on the old place— any other well-heeled young lady would have done just as well. Furthermore, the scheme by which Paul Mallen sought to neutralize his wife after she inadvertently discovered evidence that he wasn’t who he claimed to be followed logically from her personality; he knew she could be driven mad because she had already had mental and emotional breakdowns in the past. Gregory’s plan to drive Paula insane, by comparison, is a shot in the dark. But while it may not be quite up to the level of its predecessor, the MGM Gaslight remains an extremely good film. There is no dishonor whatsoever in failing to meet such a high standard as the British National Gaslight set four years before.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact