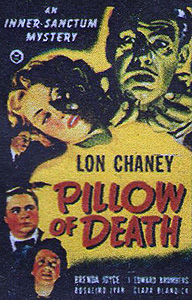

Pillow of Death (1945) -***

Pillow of Death (1945) -***

I don’t think it’s even theoretically possible to make a movie without subtext— a film with no implications, intended or otherwise, regarding (for example) its creators’ social, political, or moral outlook. The most readily legible subtext in Pillow of Death concerns something else altogether, though. Read between the lines here, and the first message you’ll encounter is, “You know what? Fuck it. We don’t even care anymore.” Universal’s Inner Sanctum Mysteries had never been conspicuously ambitious, but they generally did at least attempt to do something new or at any rate interesting along the way to filling up an hour of the audience’s time. Calling Dr. Death experimented (albeit ineptly) with film noir styling. Weird Woman put a vaguely Lewtonian psychological spin on a nominal tale of witchcraft and paganism. Dead Man’s Eyes and Strange Confession proceeded from premises that pushed the limits of permissible gruesomeness under the censorship regime of the mid-1940’s. Pillow of Death, though? Perish the thought. Pillow of Death is a spooky-house mystery full of bogus ghosts and fraudulent séances, and I can’t think of any plot template further past its expiration date in 1945 than that. And as a tacit admission that Universal were abdicating whatever lenient standards the Inner Sanctum series might ever have maintained, Pillow of Death even omits the signature introductory spiel from the floating head in the crystal ball! Nevertheless, this singularly hapless movie is easily the most entertaining of the lot, with Wallace Fox directing George “Sh! The Octopus” Bricker’s daffy script with much the same dim-witted enthusiasm that he brought to The Corpse Vanishes over at Monogram.

The spooky house here belongs to Belle Kincaid (The Drums of Jeopardy’s Clara Blandick) and her slightly less elderly brother, Samuel (George Cleveland, from All that Money Can Buy and Revolt of the Zombies). The Kincaid siblings are equally irascible and eccentric in their own ways, and both accept more or less uncritically that the family mansion is haunted by generations of ghosts— although Belle alone among the pair has any interest in making contact with the restless spirits of their ancestors. Instead, she shares her occult hobby with Amelia (Rosalind Ivan, of Pursuit to Algiers), the poor relation from England who acts for all practical purposes as the Kincaids’ maid. Belle and Amelia’s guide in their efforts to communicate with whomever is behind the nocturnal sniggering and rattling of chains in the attic and the unaccountable opening and closing of doors throughout the house is spiritualist Julian Julian (J. Edward Bromberg, from Queen of the Amazons and The Invisible Agent), who has lately discovered that another patron of his by the name of Vivienne Fletcher is a “perfect medium” for interacting with the spirit world. Rather than talking to the ghosts directly, Julian now puts Vivienne into a trance, and lets her do the hard work. Nor is that the Kincaid family’s only connection to Vivienne Fletcher, oddly enough. Her semi-estranged husband is the locally influential attorney, Wayne Fletcher (Lon Chaney Jr.), under whom Belle’s niece, Donna (Brenda Joyce, of Strange Confession and The Spider Woman Strikes Back)— evidently the daughter of yet a third sibling, now deceased— has recently taken a job as a secretary. This is a point of acrimonious contention between Donna and Belle, for in Belle’s day, none of the Kincaid women would have considered working for a living. They just sat around the mansion looking glamorous until their parents found them a man rich enough for them to marry without bringing shame and disgrace to the family name. Belle considers working for Wayne Fletcher tantamount to having an affair with him, and although her position is patently unreasonable, Donna’s protestations to that effect are undermined somewhat by the fact that she is having an affair with her boss.

So you can see how inconvenient it is for everybody when Vivienne is discovered dead, apparently smothered in her bed with her own pillow. Wayne and Donna had been at the office late that evening, catching up on backlogged work, and as Fletcher dropped his secretary off at the Kincaid mansion, he told her that he was planning on forcing the issue of his disintegrating marriage when he got home, and telling Vivienne that he wanted a divorce. Belle, meanwhile, had paid her own visit to the Fletcher residence, hoping to use her pull with Vivienne to get Donna fired. When Fletcher arrives at his house, he finds it crawling with cops under the command of Detective Captain McCracken (Wilton Graff, from The Unknown and Valley of the Zombies), and none other than Julian Julian in the living room, explaining how he had a “psychic presentiment” that Vivienne had come to harm. McCracken may not buy that part, but he seems more than willing to consider Julian’s surmise that Wayne killed his wife because he wanted to clear the decks for an out-in-the-open romance with Donna. However, a visit to the Kincaid place raises several other possibilities. Maybe Donna herself was the killer, since she obviously stood to gain exactly the same thing as Wayne from the elimination of Mrs. Fletcher. Or perhaps it was Belle— who, let us not forget, is the last person who’ll own up to seeing Vivienne alive— seeking to frame Wayne after her efforts to detach him from her niece by less radical means failed. Or it might have been a frame-up gambit by Bruce Malone (Bernard Thomas), the Kincaids’ next-door neighbor, a childhood friend of Donna’s whose unrequited love for her turned obsessive and creepy a long time ago, and whom McCracken catches spying on the goings-on in the parlor through the window. And for whatever this is worth, Julian’s fakery is exposed for anyone who has eyes to see and a brain to think when McCracken investigates the much-discussed laughing and rattling from the attic (which Julian attributed to the ghost of Belle and Samuel’s Uncle Joe), and discovers that the noises are being made by the recently escaped semi-tame raccoon which another neighbor used to keep chained to a stake in the backyard. McCracken does eventually place Wayne under arrest, but ends up releasing him the next morning as soon as Fletcher utters the magic words, habeas corpus.

The case quickly becomes more complicated. On the night after his release, Wayne attends a séance at the Kincaid mansion, where Julian supposedly channels Vivienne’s spirit, getting from the ghost an explicit accusation of her husband’s culpability. Bruce Malone just happens to be lurking right outside the room at the time, too, although he and Julian each disavow any collusion with the other when Fletcher drags the skulking lad into sight. Then a few hours later, Wayne hears Vivienne’s voice coaxing him to follow her to the Fletcher family crypt— in fact, Wayne later tells McCracken that he actually saw Vivienne, although we in the audience do not. When the detective orders Vivienne’s vault opened up, there’s no trace of a body inside. Meanwhile, Samuel Kincaid dies in exactly the same way as Mrs. Fletcher, and this time the most damning evidence points toward Julian. As Donna reports, Sam had been looking into the psychic’s background, and had just uncovered Julian’s membership in a guild of Vaudeville performers. Crucially, he used to work as both a ventriloquist and an imitator of voices. As he did with Fletcher, though, McCracken ultimately concludes that the evidence isn’t good enough to keep Julian for more than an overnight stay in a holding cell. Finally, Belle is suffocated, too, and Pillow of Death completely loses its fucking mind.

I compared The Frozen Ghost to a Monogram production before, but the likeness is even stronger with Pillow of Death. Obviously the Wallace Fox connection is a factor there, yet The Corpse Vanishes is not the movie this one most closely resembles. Rather, what I’m reminded of most is The Invisible Ghost, for only there is the breakdown of story logic and character motivation so complete in so purely irrational a way. In both films, the seemingly mild-mannered star is really the killer, murdering in a fugue state that has something to do with his wife. There’s one big difference, though, in that The Invisible Ghost at least had the relative good sense to establish that ridiculous fact right up front, and to provide a concrete stimulus for bringing on those deadly trances. Pillow of Death, in contrast, springs Wayne Fletcher’s psychosis on us as a surprise ending, and never quite gets around to presenting any reason for it. One minute, he’s pulling an all-nighter in the hope of spotting some pattern in the mystery that McCracken has thus far missed, and the next, he’s wandering around the Kincaid mansion talking aloud to Vivienne’s imagined ghost about how he committed the crimes. Nor is there much sense to be extracted from whom Fletcher kills or when. Vivienne, sure. Their marriage was falling apart, and from the way Wayne talks, I wouldn’t put it past her to have refused a divorce simply out of spite. Belle I can also see, since she’d been meddling in Wayne’s relationship with Donna from the start, and was furthermore the most vociferous member of the Wayne Fletcher Is a Murderer party. But why kill Samuel? He was the only one of Donna’s relatives who had a single kind word to say about Wayne. Fletcher had no reason to want him dead, and negative reason to want him dead so long as Belle was in the picture! It puts a curious spin on McCracken’s dithering and ineffectual investigation in retrospect; maybe he isn’t incompetent at all, but merely the most genre-savvy B-movie detective of his age. Since a rational interpretation of the evidence in films of this sort usually implicates an innocent character even when the script wasn’t apparently written by deinstitutionalized mental patients, perhaps he’s playing it smart by simply marking time until the truth inevitably comes out through no action of his, just in time for him to intervene on the side of law and order at the climax.

The killer’s identity isn’t the screwiest thing about Pillow of Death, though, nor is it the most Monogramatic. For those laurels, it’s a tossup between a pair of subplots that come to no resolution whatsoever, despite concerning crimes only slightly less serious than a triple murder. You remember how Vivienne’s tomb was empty when McCracken went to look inside it? Well, it turns out that Bruce Malone stole her body as part of some cockamamie scheme to make Wayne confess. The corpse eventually pops up in the network of secret passages that Bruce uses to sneak into and around the Kincaid mansion. And would you like to guess what Donna’s compulsively trespassing, window-peeping stalker gets for adding grave-robbing to his resumé? Why, he gets Donna, of course, and not so much as a stern talking-to from McCracken in the aftermath! And as if that weren’t enough “What the fuck?” for 67 minutes, there’s also a scene in which Amelia goes shithouse crazy after learning that Julian has been arrested, and tries to gas Wayne and Donna to death in a walk-in linen closet! This isn’t even mentioned subsequently, so I can only conclude that the murderously senile old bat stays on as Donna’s housekeeper when she and Bruce live codependently ever after on the far side of the closing credits. It’s almost as if the filmmakers are attempting to set up a sequel that jumps genres from spooky-house mystery to 20th-century gothic— which, come to think of it, makes me just a little bit sad that we didn’t get a seventh Inner Sanctum movie to follow through on that premise in 1946.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact