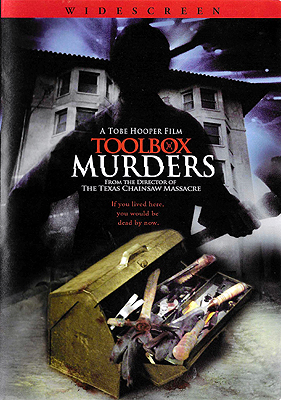

Toolbox Murders (2003) **

Toolbox Murders (2003) **

Some of you may remember me speculating that The Toolbox Murders would have been a very different sort of film if it had been made immediately after Halloween instead of immediately before. Well, Tobe Hooper’s Toolbox Murders hardly counts as immediately post-Halloween, but it nevertheless demonstrates approximately what I was driving at in making that assertion. The original The Toolbox Murders is most noteworthy for not being a slasher movie in any but the very loosest sense, despite incorporating virtually every feature that would characterize the North American slasher formula once it was fully codified at the turn of the 80’s. The remake, meanwhile, is very much a slasher movie, albeit one that prominently displays the restlessness and dissatisfaction with the rigidity of the old rules that have become emblematic of the subgenre since the late 1990’s.

Steven and Nell Barrow have just moved to Los Angeles to begin their married life. Steven (Brent Roam, from Deep Blue Sea and Tremors 4: The Legend Begins) is nearing the end of medical school, and is about to begin his hospital residency at Wilshire Memorial. Nell (Angela Bettis, of Bless the Child and the made-for-TV Carrie) is a teacher, but has yet to find a school in need of her services. Incoming money, as you might imagine, is therefore in rather short supply, and the move from wherever the couple lived before ate up most of their savings. With their housing options thus limited, it is perhaps understandable that Steven would jump at the “renovation special” advertised by the Lusman Arms residence hotel: $900 for a security deposit and the first two months rent-free. Unfortunately, it’s obvious that the reason for those generous terms is that nobody would be willing to stay at the Lusman Arms otherwise. Those renovations are sorely needed, and Nell is being unfair only to Steven when she asks him whether he was aiming more for the Third Circle of Hell or the Fourth when he selected their new abode. The elevator is wonky, the plumbing is terrible, and the wiring is literally disastrous; on the day of the Barrows’ arrival, the lead electrician is fatally electrocuted while repairing a junction box on the third floor. The interior walls are also paper-thin, so Nell and Steven can look forward to getting to know their eccentric neighbors (not since Private Parts has this much weirdness been concentrated under the roof of a single hotel) far better than they would ever wish to. Byron the building manager (Greg Travis, from Mortuary and Showgirls) is a smarmy dickweed who takes glaringly misplaced pride in his hotel’s “unique character” while going to great lengths to avoid dealing with any of its equally glaring defects, and Ned the handyman (Adam Gierasch, of The Hollow and Crocodile) makes the creepy high school janitors in Prom Night and Cutting Class look positively charming. Oh— and someone among the residents of the Lusman Arms is a serial killer. While Steven and Nell have all their attention focused on the more mundane annoyances of stinky, brown tap water and a stove that doesn’t work, the aspiring actress down the hall in suite 312 (Sherri Moon, from House of 1000 Corpses and The Devil’s Rejects) has her flat broken into by a masked, black-clad man who proceeds to beat her to death with a claw hammer.

Nell’s first 24 hours mostly alone at the Lusman Arms do not improve her opinion of the place any. Naturally high-strung and set on edge immediately after Steven gets called in for an overnight shift by an intense shouting match between Saffron next door (Sara Downing, of Rats and The Forsaken) and her skinhead boyfriend, Hans (Charlie Paulson), Nell has little reserve emotional buoyancy with which to withstand Byron’s dodging, Ned’s lurking, or the thousand minor mechanical annoyances presented by the Lusman Arms. Nell gets a brief respite in the basement laundry room, when she makes the acquaintance of retired actor Chaz Rooker (Rance Howard, from Ticks and Village of the Giants), but even that interaction has a dark undercurrent. Chaz has lived in the old hotel since 1947, and his ramblings during the initial chat with Nell keep wandering back toward disquieting things that have happened there over the years. That electrician yesterday turns out to have been far from the first workman to have died on the premises, for instance, and Rooker also mentions the disappearance of Jack Lusman, who instigated the building’s construction, and alludes to strange “proclivities” Lusman shared with a circle of film-industry types who formed the hotel’s original clientele. Then Nell hears the screams of terror and/or agony coming from suite 313. Assuming (perhaps not unjustly) that something horrible is happening at the other end of the hall, she immediately calls the police, but all she accomplishes thereby is to make an enormous fool of herself. The tenant in 313 is another would-be actor, and he was merely rehearsing for a forthcoming movie audition. Steven thinks it’s hilarious when Nell tells him about it in the morning, but Nell herself doesn’t see much humor in the situation. She sees even less humor in the art deco jewelry box full of human teeth that she finds in the wall of her own unit when she accidentally knocks a hole in the plaster while moving furniture around. In fact, that little discovery nearly ends the Barrows’ tenancy at the Lusman Arms, before Bryon reminds them that they will not be getting their $900 back if they break the lease. No way can the couple afford to take that hit, and thus Nell finds herself alone in the apartment again the second night, listening through the wall as Saffron is nail-gunned to death. She makes a second report of anguished screaming, but her performance the preceding evening has not done wonders for her credibility. The cops do indeed get Byron to unlock suite 302 for them, but when the place looks empty on cursory examination, they bail on the more thorough check that would have led them to notice the victim’s body nailed to the bedroom ceiling right above the door.

The one solidly good thing that happens to Nell after moving to the Lusman Arms is meeting and befriending Julia (Juliet Landau, from Neon City and The Yellow Wallpaper), the tenant in 310. Unfortunately, that doesn’t last long, because Julia is the killer’s next target. Nell pursues every angle she can think of when her new friend disappears— Byron, Ned, Luis the doorman (Marco Rodriguez, of Unspeakable and The Crow), the skeezy kid in 309 (Adam Weisman, later seen in Rob Zombie’s Halloween) whose parents she overhears talking about him spying on Julia by hacking the signal from her webcam— but oddly enough it’s old Chaz Rooker who comes through with something useful, slipping Nell a note reading “Look for her in room 504” while making small talk about his acting career in the 50’s and 60’s. When Nell goes looking for 504, she finds that there is no suite with that number— and indeed that every floor in the Lusman Arms is missing a unit 4. A visit to the municipal archives (where the Lusman Arms blueprints are stored) turns up the startling information that the “missing” rooms actually do exist, hidden for some inexplicable reason in a part of the hotel with no apparent means of ingress. The employee Nell talks to there also proves to be a fount of information regarding those “proclivities” Rooker hinted at in the laundry room; evidently Jack Lusman was an occultist, and had a spell of some kind literally built into the hotel. That would certainly explain the strange plaques bearing mystical symbols that are mounted in the walls all over the building. And if Nell is reading those blueprints right, the plaques in question collectively mark out the positions and limits of the hidden rooms. Now it’s just a matter of finding the entrance to the secret apartment— and of uncovering whatever trace there is to be found of Julia while avoiding the attentions of the killer who is almost certainly using the place as his lair.

I started off this review by suggesting that Dennis Donnelly’s and Tobe Hooper’s respective versions of The Toolbox Murders can be seen as signposts along the developmental route of the slasher movie: Donnelly’s, made while the formula for such movies was still taking shape, is like a prototype that was never selected for series production, while Hooper’s, made twenty years after the spawn of Halloween and Friday the 13th had started to lose their allure for everyone outside a tightly circumscribed niche audience, is almost purely generic. In that light, it’s significant that the killer in this Toolbox Murders is eventually revealed to be the long-missing Jack Lusman, and that his present murder spree is somehow tied in with the immortality magic built into the floor plan and decorative scheme of the Lusman Arms. The most prominent strategy whereby the makers of slasher movies sought to maintain interest in the genre after 1984 was by giving the murderer some manner of supernatural quality, and it is therefore a sign of the times that the man carving up the hotel’s tenants has been upgraded from the original Toolbox Murders’ overly religious lunatic to a dead ringer for The House By the Cemetery’s Dr. Jacob Freudstein. Similarly in keeping with contemporary genre developments are the substantial roles played by Steven, Bryon, Luis, Rooker, and even the pervert kid from 309 in the movie’s climax. Among the less widely remarked ways in which the post-Scream generation of slasher films sought to combat formula fatigue was by abandoning strict adherence to the convention of the Final Girl, although that convention obviously continued to influence the way they handled their heroines. In Toolbox Murders, Nell begins her confrontation with Lusman alone in standard Final Girl style, but all of the aforementioned males subsequently intervene on her behalf with varying degrees of success.

Only about half of Toolbox Murders’ weaknesses stem from it being exactly the movie that an attentive student of the slasher subgenre would expect in a well-funded direct-to-video production from 2003. The other half are the result of Toolbox Murders being not quite well-funded enough. Apparently a significant portion of the financing fell through when the movie was already well underway, and the producers were unable to find substitute money elsewhere. Fully a third of the script had yet to be shot when the cash ran out, and Hooper was forced to make do with whatever he had in the can once the last dollar was spent. Knowing that explains at a stroke a great many of the film’s more irritating defects. Flabby editing and scenes that seem to take far too long to get to the point? Full feature length had to come from somewhere after Hooper and company were forced to shitcan over 30% of the story! Loose ends dangling left, right, and center regarding Lusman’s aims, methods, timing, and even choice of weapons? Well, what do you think was covered in all those pages that never got filmed? Ridiculously inconclusive ending that only superficially resembles the traditional “It’s not over yet!” slasher coda? Odds are that scene was never intended to be the ending in the first place. Frankly, it’s astounding that Toolbox Murders came out as coherent as it is under the circumstances, but having a valid excuse for looking shoddy and unfinished doesn’t make it any more satisfying to watch.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact