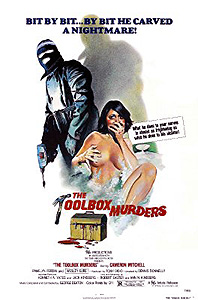

The Toolbox Murders (1977) **½

The Toolbox Murders (1977) **½

If The Toolbox Murders had been made even a single year later, I’m quite certain it would have been a completely different film. When I sat down to watch this movie, my expectation was that it would be another example of the process whereby North America’s version of the slasher genre groped its way along from Black Christmas and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre to Friday the 13th and the ensuing deluge of rip-offs. I guess you could look at it that way, too, but to an even greater extent than the other pre-Halloween proto-slashers, The Toolbox Murders represents a path not taken. Although its first act plays like a giallo on fast-forward, it quickly shifts gears to become, if anything, more a distant antecedent of today’s captivity-and-torment school of horror instead.

Nevertheless, there really is no mistaking the body-counting intentions of that opening half-hour— and goddamn but it racks them up fast! A 40-ish woman (Faith McSwain) receives what she thinks is a long-awaited visit from her apartment complex’s handyman, but the electric drill he produces from inside his toolbox goes not into the drywall (or whatever), but into her. The woman puts up a decent fight, all things considered, but she really doesn’t stand a chance. Donning a ski mask to conceal his identity (probably not a bad idea now that he’s got blood all over him), the killer then proceeds downstairs to a second apartment, where he catches the tenant (Marciee Drake, of Jackson County Jail and Jokes My Folks Never Told Me) on the threshold, knocks her unconscious, and whisks her away to the relative privacy of the nearest stairwell. Then he smashes her head in with a claw hammer, and carries her body back to the apartment. He’s still there when the second victim’s girlfriend (Evelyn Guerrero, from Fairy Tales and Alligator II: The Mutation) drops in for a visit, so he ambushes her, too, and stabs her to death with a screwdriver. Evidently he’d like to make yet one more stop after that, but the woman in 302 (Victoria Perry) has her boyfriend (Robert Bartlett) over, and I don’t suppose there’s anything in that toolbox that makes a good ranged weapon. Besides, it’s obviously only a matter of time before somebody notices the gallon or so of blood leading from the stairwell to the lesbian’s flat and raises a ruckus. Our killer’s mama didn’t raise no fools, and he cuts short the murder spree for the night— although the lingering stare he gives in the direction of units 12 and 29 suggests that he isn’t finished yet. In the meantime, Detective Lieutenant Mark Jamison (Parts: The Clonus Horror’s Tim Donnelly) will be plenty busy enough interviewing both every resident he can find and building superintendent Vance Kingsley (Cameron Mitchell, from Flight to Mars and The Swarm) about the victims, their associates, and anything unusual (apart from the obvious, I mean) that might have occurred that evening. Not that doing so will accomplish very much…

The killer does indeed return the following night, and while the nail-gun shooting of the model who lives in apartment 12 (Marianne Walter, who spent the 80’s and 90’s making hardcore porn under the alias Kelly Nichols) marks the end of the bloodbath, it isn’t quite the last crime to be committed on the premises. Upstairs in 29, fifteen-year-old Laurie Ballard (Pamelyn Ferdin, from Daughter of the Mind and The Beguiled) is alone in the flat, her mother (Aneta Corsaut, of Bad Ronald and The Blob) working the night shift at the local bar and her brother, Joey (Diary of a Teenage Hitchhiker’s Nicholas Beauvy), out at the movies. Rather than, say, dismembering her with a hacksaw or skinning her with a jack plane, the killer merely overpowers Laurie and absconds with her to who-knows-where. In the aftermath, Lieutenant Jamison, genius that he is, will alternate between refusing to accept that Laurie was kidnapped at all (preferring to believe that she has eloped with a boyfriend nobody ever heard of) and trying to find some way to pin her disappearance— and the murders as well— on Joey.

That being so, it’s more than usually understandable that the boy would take it upon himself to investigate the crimes. He gets a lucky break early on when he learns that his classmate and Vance Kingsley’s nephew, Kent Miller (Jennifer’s Wesley Eure), has been hired by the super to render the crime-scene apartments rentable again once the police are finished picking them over. Kent is as work-averse as any eighteen-year-old, so he’s happy to accept Joey as a helper on what most people (albeit not Kent) would consider the rather distasteful cleanup gig. That gives Joey access to all the places where the women died, and with it a chance not only to examine whatever physical evidence remains, but to overhear a bit more cop-talk than he would normally be privy to. Joey thus learns about the unusual nature of the murder weapons, the lack of evidence of break-ins except at unit 12 (where the security chain was cut, although the regular locks were undamaged), and the absence of any clear connection between the victims save their residence in the same building. Jamison may be starting to favor the hypothesis that the killer hoodwinked his way into the women’s flats, but Joey has another idea. What if the murderer didn’t need to bluff or break his way into the apartments? What if he was somebody who the victims figured had every right to come inside?

Now who might meet such a description? We know that the first victim thought the killer had come in belated response to a service call. Admittedly, she might have assumed that simply because he was carrying a toolbox, and the murderer might just have lucked into a target who really was expecting a repairman, but it could also mean that the killer was someone she expected to see in that capacity. Someone like Kent Miller, perhaps? If Uncle Vance has him cleaning the blood and brains out of the walls and carpeting, isn’t there a pretty good chance that Kent is also his uncle’s go-to guy for routine maintenance and repairs? Or what about Vance himself? We also know that the killer had a key to apartment 12, and would have left no sign of forced entry even there, were it not for the security chain. The building superintendent would surely have access to all the units’ keys, and whom would one of the residents be more likely to open the door for than him? Joey starts thinking along these lines pretty quickly. He uses his first opportunity to be alone in the garage where Kingsley stores all his equipment and supplies to give everything a once-over, discovering in the process that Vance’s toolbox has some awfully suspicious stains collected in its hard-to-clean nooks and crannies. Consequently, the only reason we’ll be surprised to see Laurie bound and gagged in the bedroom that used to belong to Kingsley’s daughter, Cathy, is that the movie is only half-over when it happens. Obviously the mystery of the killer’s identity is not going to be The Toolbox Murders’ main game after all.

The Toolbox Murders may not be an especially good movie, but it is a fascinating one. All the elements that make up the typical slasher film are here, but they’re put together upside down and inside out, so that the finished product is something else entirely. The stalk-and-slash phase of the proceedings is compressed even more drastically than in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, wrapping itself up within the first half-hour. What would normally be The Toolbox Murders’ Final Girl sequence— that is, its showdown between the killer and an extremely resourceful female target who vigorously fights back with every physical and psychological means at her disposal— begins just a little past the twenty-minute mark, and it pits Vance not against the virginal Laurie, but against a character who has been marked for murder explicitly because of her libertine ways. What’s more, for all her cleverness and ferocity, she is ultimately no match for a loony with a nail gun. In contrast, Laurie’s eventual revolt against her captor happens completely off-screen, with only the aftermath presented— as if to imply that the details of her revenge comprise a thing too horrid to contemplate. The expected failed rescue attempt by a male character is here, too, but it comes to grief not at the hands of the killer, but at those of a hitherto little-suspected secondary villain who is in some ways even more dangerous. The inability of the police to deal effectively with Kingsley’s crimes is used as a significant plot point (rather than simply being taken for granted as a genre commonplace), yet so is Joey’s lack of preparedness as an amateur detective. Perhaps the most interesting departure, though (conceding how problematic it is to speak of a movie “departing” from a formula that hasn’t been fully codified yet), is The Toolbox Murders’ overt treatment of the slasher genre’s most oft-remarked subtextual theme. The fully developed slashers of the following decade are often interpreted (and even more often willfully misinterpreted) as reactionary morality plays in which youthful hedonism is ruthlessly punished by machete-wielding puritan avengers, regardless of (if not indeed in defiance of) the killers’ motives as expressed in the action and dialogue itself. The Toolbox Murders, however, is perfectly upfront about the role of Vance Kingsley’s conservative values in motivating his crimes. A drunk, a lesbian couple, a sexually outgoing professional exhibitionist— the victims of Kingsley’s murders all die because they offend his moral sensibilities. Meanwhile, he kidnaps Laurie Ballard partly because he believes that he can do a better job safeguarding her innocence than her unmarried, middle-aged barmaid of a mother, and partly because he considers it his moral right to claim her as a replacement for his own similarly unsullied daughter, who was killed in a traffic accident several years earlier (when she was the same age as Laurie is now). It seems to me that this ought to make The Toolbox Murders immune to the usual lazy accusations of sex-negative misogyny, for it directly attributes to the villain exactly the attitudes that liberal critics might suspect the filmmakers of harboring. And as if that weren’t enough, the movie takes the extra step of revealing Kingsley for a hypocrite as well as a homicidal maniac, having him succumb to the model’s wiles when she attempts to buy an opening to counterattack with a show of feigned sexual submission. Curiously, however, that aspect of the duel in unit 12 doesn’t become apparent until much later, for we have no idea what’s behind Kingsley’s rampage of slaughter while it’s actually in progress.

And with that, we begin to see what prevents The Toolbox Murders from being more effective than it is, and to suspect why it had so little impact on future horror movies. The very structural anomalies that make it interesting also make it trying and ungainly. The opening outburst of bloodshed raises expectations that the rest of the film isn’t even interested in living up to, which would be a problem even if the unit 12 set-piece at the close of the first act— a minor marvel of 70’s-ness that manages to be rousingly cathartic, depressingly downbeat, and squirm-inducingly exploitive all at the same time— weren’t far and away the best scene in movie. There’s something uniquely satisfying about a film (like, say, The Professional) that focuses on well-written characters being really good at their jobs. Conversely, it’s uniquely unsatisfying to spend scene after scene watching indifferently written characters kind of sucking at theirs, and The Toolbox Murders shows us an awful lot of that during its limp and draggy midsection. It would be a mistake to assume that The Toolbox Murders has lost its sense of direction after Laurie’s abduction— actually, it’s just changed directions so drastically that it’s moved onto a different page of the atlas— but knowing that doesn’t render the long foray into half-assed and half-hearted police procedural territory any easier to sit through. The damn fine job that Cameron Mitchell does with the character-study stuff in the scenes where Vance and Laurie are alone together never has the impact that it should, simply because there isn’t quite enough of it to go around, and in any event, even that material is a far cry from what viewers will naturally be looking for based on the first act. What The Toolbox Murders really needs is a better equilibrium among its several aspects and tonal identities.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact