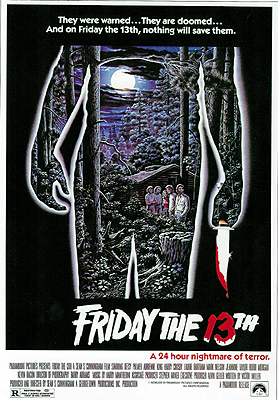

Friday the 13th (1980) **½

Friday the 13th (1980) **½

With the impending release of Jason X looming pestilentially before us, it seemed as good a time as any for me to revisit the original Friday the 13th, which I had not seen in something like nine years. I must say I’m surprised at how well it’s held up. Unlike most fans with sufficiently discriminating tastes to draw the distinction in the first place (among whom the consensus seems to be that Parts 1 and 2 are the only ones worth bothering with), I never much liked the first two entries in the Friday the 13th series. I thought they were kind of dull, and preferred the unapologetic stupidity of Parts 3 and 4, along with the desperate loopiness of the much-maligned Part VII. But with most of my adolescent impatience leeched away by the passing years, and with a recently acquired familiarity with the slasher movie’s Italian roots to help me spot how writer Victor Miller and director/producer Sean Cunningham picked and chose among the elements of the subgenre’s heritage, I now see that this film is at least a little bit better than I had given it credit for.

Like Halloween, Friday the 13th’s most direct inspiration, this flick’s story has the raw, brutal simplicity of a boy scout’s campfire tale. Way back in 1958 (or so says the caption, anyway— too bad nobody bothered to tell the hair, makeup, and wardrobe people that...), a boy and a girl employed as counselors at Camp Crystal Lake snuck away from their “Michael, Row the Boat Ashore”-singing friends to have sex in the attic of one of the cabins. They were cut up by somebody with a very big knife before they even finished taking their clothes off. As you might imagine, this got the camp closed down, and it has remained that way for more than twenty years.

Flash forward to “the present” (or at any rate, the early 1980’s). Steve Christy (Peter Brouwer), a man from the nearest town to Crystal Lake, has bought the old campsite from relatives, and has sunk some $25,000 into reopening it, despite the naysaying of his neighbors, who have never forgotten what happened all those years ago at “Camp Blood.” The refurbishment is almost complete, and Christy has just hired seven teenagers to serve as counselors for the camping season, which is slated to begin in another week. Our introduction to all this comes from Annie (Robbi Morgan), the girl whom Christy hired to run the kitchen, and whom we see hitchhiking her way to the camp after the opening credits finish up. She tells the trucker giving her a ride about Steve Christy, while the trucker and a loony old man called Crazy Ralph (Walt Gorney) fill her in on the outlines of the camp’s less-than-flattering history.

Meanwhile, three more counselors— Bill (Harry Crosby), Marcie (Jeannine Taylor), and Jack (Kevin Bacon, from Tremors and Flatliners, the only member of the cast to have much of a subsequent career outside of the stock footage that would become a signature feature of the ensuing sequels)— are also on their way to Camp Crystal Lake, but they have the good sense to get there via Bill’s pickup truck. Upon their arrival at the camp, they are greeted by Mr. Christy, who then introduces them to Alice (Adrienne King), Brenda (Laurie Bartram), and Ned (Mark Nelson), their fellow counselors. Then it’s work, work, work as the scramble to get the place ready for the influx of pre-teen campers begins in earnest, with a couple of interruptions along the way for the usual teenage hijinks and for red herring-establishing encounters with Crazy Ralph and a menacing, teen-hating cop. It is during this phase of the film that we learn into which stereotypical categories our young heroes fall: Alice is responsible, artistic, and not interested in amorous advances from men ten years her senior; Brenda is also responsible, but she’s a bit more worldly and outgoing than Alice; Jack and Marcie can’t seem to keep their hands off each other; Ned is the dipshit practical joker; and Bill has no recognizable personality traits whatsoever. And none of them (with the possible exception of Alice) seems to be particularly bright.

You might have noticed that I didn’t say anything about Annie in that little rundown. That’s because she never makes it to Camp Crystal Lake. The trucker drops her off after taking her as far in the direction of the camp as his intended route goes, and soon afterward, Annie is picked up by another driver in a blue Jeep Wrangler not unlike the one we saw Steve Christy driving as he left for town in the previous scene. It is immediately obvious that Annie is in a world of shit at this point, because the camera pointedly fails to show us the Jeep driver’s face, nor does the driver ever say a single word to the hitchhiking girl. We will therefore be none the wiser as to the killer’s identity when Annie ends up with her throat slit. The body count has officially begun.

Ned is the next one to go. (Big surprise there. The dumb shitbag should count himself lucky to have survived until the killer made it to the camp!) Soon after playing the last stupid prank of his life, he wanders into one of the more isolated camp buildings in pursuit of someone he thought he saw skulking around inside it, and finds that his perceptions were right on the money. Jack and Marcie are next. When the requisite thunderstorm blows up, they take cover a cabin and engage in one of the more convincing sim-sex scenes I’ve encountered. (Fans of celebrity nudity take note: this scene features a quick peek at Kevin Bacon’s bare ass.) With the unerring bad luck of all sexually active young people in movies of this sort, Jack and Marcie have chosen the cabin in which the killer was hiding Ned’s body (in fact, it’s stashed on the top bunk of the very bed in which they’ve been fucking so obliviously), and no sooner has Marcie left the room for a post-coital trip to the bathhouse than Jack gets impaled through the throat with an arrow from beneath the bed. The killer then follows Marcie to the bathhouse and buries an axe in her face. (Chief makeup guy Tom Savini has clearly seen Twitch of the Death Nerve...)

So what are the rest of our Expendable Meat up to while all this is going on? They’re playing Strip Monopoly, of all things! Bill is losing badly (he’s down to his underpants) and Brenda isn’t faring much better. But just as Alice is about to forfeit her shirt for landing on one of Bill’s properties, the developing storm blows the cabin door open, and Brenda realizes she’s left the windows open over at her place. Brenda grabs her raincoat (she inexplicably leaves the rest of her clothes behind) and runs off alone, ensuring that she will be next on the killer’s menu. Surprisingly, she doesn’t get her ticket punched right then and there, but lasts until a bit later that evening, when she is decoyed out to the archery range by what appear to be a child’s cries for help. The brief flash of the archery range floodlights illuminating Brenda for easier slashing alerts Alice and Bill that something untoward is going on, and the surviving counselors’ investigations promptly get Bill killed. Not only that, Steve Christy has also had a run-in with the maniac— unbeknownst to Alice, who has just become our Final Girl for the evening.

It is at this point in the film that the most puzzling twist in the plot occurs. A familiar-looking blue Jeep drives up while Alice (who has begun finding the artfully hidden bodies of her fellow counselors) frantically fortifies the cabin where she had so recently been playing Strip Monopoly without a care in the world. The Jeep disgorges a woman who, when Alice stupidly dismantles one of her barricades to let her in, introduces herself as Mrs. Voorhees (minor 50’s TV personality Betsy Palmer), a former employee of the Christy family. What do I find so puzzling about this? Okay, consider: So far, Friday the 13th has, like the scores of gialli before it, been presenting itself as a sort of super-violent murder mystery. Unlike in Halloween or The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, in which the identities of the killers are deliberately made immediately obvious, Cunningham has been at pains to keep his murderer off camera for the last 70-odd minutes. He’s even gone so far as to plant misleading clues in the form of Crazy Ralph’s obsession with the “Death Curse of Camp Blood,” the policeman’s apparently unmotivated hatred of teenagers, and Steve Christy’s blue Jeep. And then he goes and introduces this character whom we’ve never seen before, under such circumstances that she could be no one in the world but the killer. It just doesn’t make any sense.

Anyway, Mrs. Voorhees hasn’t been in the cabin with Alice for two minutes before she starts talking crazy, prattling on about how she used to work at Camp Crystal Lake back in the 50’s, and how she was there not only on the day that the two counselors were stabbed to death, but also on the day of the preceding year when a camper named Jason drowned because the counselors were too busy hiding the salami to notice that he had gone swimming unsupervised. By the time Mrs. Voorhees gets around to mentioning that Jason was her son and that today was his birthday, even Alice has gotten the picture, and thus commences at least an entire reel’s worth of cat-and-mouse showdown between the two women, culminating in one of the all-time great beheadings in special effects history. Having survived the night (just barely), Alice grabs a canoe and floats herself out onto the lake, where she should be safe from just about anything else the filmmakers care to throw at her. Anything, that is, except the waterlogged zombie boy that leaps out of the water the next morning and pulls her under, just as the police arrive on the scene to pick up the mess. The following comparing-notes-around-the-survivor’s-hospital-bed scene raises the question of whether the folks responsible for this movie had any more idea than the audience of whether that Carrie-wannabe kicker ending was supposed to be real, a dream, a hallucination, or what.

Whatever its faults, there can be no contesting the historical importance of Friday the 13th. For better or for worse, it accomplished what an entire decade-and-a-half’s worth of gialli and such isolated North American experiments as Halloween, Black Christmas, and The Town that Dreaded Sundown could not. It turned the English-language slasher movie into a self-sustaining Perpetual Foolishness Machine that would run smoothly for more than ten years before grinding to a well-deserved halt in the early 1990’s. (And even then, the subgenre was not so completely dead that it couldn’t muster the occasional spasm in the years following the release of Scream.) As near as I can tell, there were two main factors accounting for this movie’s success in touching off the 80’s slasher explosion. First, in contrast to the gialli of Mario Bava, Dario Argento, and their imitators, Friday the 13th is not inscrutably European. It may not have the breathtaking visual flair that characterizes all but the worst of the gialli (although it does have one beautifully composed shot near the very end), but it also lacks the brain-curdling disregard for narrative cohesion that characterizes all but the best of them. Second, because Sean Cunningham somehow convinced a major studio to back him on the project, the wide distribution the movie received all but guaranteed that it would rake in an obscene amount of money. And when that happened, filmmakers and distributors around the world realized that you didn’t need to have the talent of a John Carpenter or a Tobe Hooper or a Mario Bava to make a profitable slasher flick. All you needed was a makeup man who could deliver halfway convincing gore effects and a handful of young wannabe actresses who didn’t mind taking off their clothes for the camera.

And if you look closely enough, it really does become obvious that most of the movies that are conventionally described as Halloween clones are really more closely related to Friday the 13th (although most of them— including all nine of the Friday the 13th sequels— would adopt one conspicuous, distracting element from the former film: the unstoppable, subhuman/superhuman killer). For example, the imaginative murders that would become the whole raison d’etre of the slasher subgenre make their American debut here. Sure, there was the trombone scene in The Town that Dreaded Sundown, but that was just one incident in just one movie. In Friday the 13th, Mrs. Voorhees repeats a modus operandi only twice (two throat-slittings via hunting knife, and two bow-and-arrow slayings), and when she repeats herself, she does it off camera. Halloween’s Michael Myers, by contrast, pretty much stuck to his carving knife, and it could scarcely have been The Texas CHAINSAW Massacre if Leatherface hadn’t limited himself to one preferred method of attack. Friday the 13th also differs from its American predecessors in supplying a motive— however cracked— for its killer. Leatherface, Michael Myers, and The Town that Dreaded Sundown’s Phantom Killer murdered for no discernable reason; they were irreducibly, inexplicably evil. Mrs. Voorhees, on the other hand, kills out of a twisted notion of revenge: the people who allowed her son to drown were camp counselors, ergo camp counselors as a class must be punished for his death. And in the wake of Friday the 13th, insane revenge motives, especially those with psychosexual underpinnings (and what is Mrs. Voorhees if not Norman Bates turned inside out?), would become more or less de rigueur for serial killers in the movies.

As for what makes this movie in particular tick, that’s a more complicated question. Frankly, Friday the 13th shouldn’t work at all. It’s next to impossible to care about the characters as individual people, the script is positively contemptuous of logic and even basic physics, and the way in which the killer’s identity is revealed shoots the film’s murder mystery aspect completely to hell. Just about all it has going for it from a conventional perspective is Harry Manfredini’s brilliantly jagged and unnerving score and a couple of hard-hitting gore effects from Tom Savini (although it’s worth pointing out how much the passage of time has dulled the impact of the latter). But somehow, Sean Cunningham turns Friday the 13th’s sheer crudity into an asset, raising the film up to just above the level of mediocrity. The directness of the slasher formula— unsuspecting young people, maniac, sharp object— is appealing in a way that is shared by many forms of minimalism. It is what it is, it does what it does, and there is really nothing more to it. The endlessly belabored “reactionary” sexual morality of the subgenre is as much of a red herring as Crazy Ralph, as are its supposed invitations to identify with the killer against the victims. Both phenomena can be most parsimoniously explained as artifacts of economic decisions: the POV-cam is the cheapest and easiest way to indicate the killer’s presence without giving away his/her identity, while the notorious “take of your clothes and die” phenomenon makes sense only as a dual money shot— the filmmakers know we’re here to see boobs and blood, so they give them both to us at once. I mean, come on— slasher movies are aimed at teenagers, teenage boys especially, and if you seriously believe teenagers think sex is something that deserves to be ruthlessly and brutally punished, you obviously haven’t known very many teenagers. The slasher movie in general, and Friday the 13th in particular, is about life vs. death, period. It pits people whose lives have scarcely yet begun against a force which kills in the most direct and primitive manner; it is to the horror genre as a whole what boxing is to sports, and it makes people who have a great investment in their own civilized refinement uncomfortable for the very same reason.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact