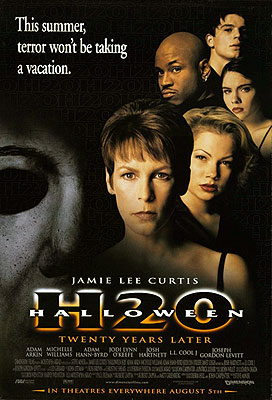

Halloween H20 / Halloween H20: Twenty Years Later (1998) ***

Halloween H20 / Halloween H20: Twenty Years Later (1998) ***

Any reasonable person observing the state of the Halloween franchise in the final quarter of 1995 would have concluded that the saga of Michael Myers was finally over for good. The most recent installment, The Curse of Michael Myers, had mutated into two drastically different films (one shown only at preview screenings, the other in general release), yet still landed with a wet thud at the box office. The most determined and longest-lasting of the series’s many producers, Moustapha Akkad, was chronically at loggerheads with Dimension Films, the company that owned the rights to distribute further sequels. And perhaps most importantly, nobody gave a shit about slasher movies anymore, outside of the dwindling corps of diehards who kept video-oriented dreck like The Dentist just barely profitable. Then Scream happened. Suddenly slashers were hip again— and slashers on the non-supernatural 1970’s model, at that! In an environment cluttered with Scream wannabes, maybe somebody other than Akkad himself would be able to work up a bit of enthusiasm for the prospect of a Halloween 7 after all.

In stark contrast to the snakebit development and production of Halloween 6, the seventh film benefited from an extraordinary run of good luck, good will, and good decisions. Although initially conceived as a direct-to-video project, it not only got a much-ballyhooed theatrical release, but ended up being the most lavishly funded Halloween film to date (even if $17 million was a modest amount to spend on a feature motion picture by the standards of the late 1990’s). The budget increase, together with the looming 20th anniversary of the original Halloween, gave Bob Weinstein, co-boss of Dimension’s parent company, the bright idea to approach Jamie Lee Curtis about returning to the series that put her on the map. Luckier still, the invitation caught Curtis at a high enough point on her career arc to engender some nostalgic fondness for her early scream queen days, however gun-shy she’d been about appearing in further horror movies in the interim. Nor was Curtis the only casting coup. Although the sole other name performer hired for a major role was a rapper enlisted specifically for demographic appeal, Halloween H20: Twenty Years Later ended up with a much higher— and much more uniformly high— caliber of young actors than any of its predecessors save Halloween itself. Akkad and Dimension got onto the same page about the direction of the project with unaccustomed speed and alacrity, agreeing to pay only the bare minimum of continuity heed to all the preceding sequels following Halloween II— and although a scene was shot acknowledging the existence of Jamie Lloyd, and the bad end to which she eventually came, that bit wisely got dropped from the final cut. In effect, then, the new Halloween film functioned as a continuity rewind in the style of Godzilla 1985. Scream writer Kevin Williamson came onboard as one of several executive producers, and at least by some accounts did some uncredited script-doctoring to make sure the film remained in line with current subgenre fashions. And finally, director Steve Miner and cinematographer Daryn Okada were each good catches in their own ways. Miner had directed the best of the Friday the 13th sequels (and a lousy one, too, to be fair), while Okada had shot Phantasm II. All in all, a big step up for what started as a quickie home-video release pitting Michael Myers against the inmates of a girls’ boarding school.

Chances are you won’t remember Marion Chambers Whittington (Death Car on the Freeway’s Nancy Stephens) from the first Halloween, but she was there just the same. Marion was the psychiatric nurse riding along with Dr. Loomis when he arrived at Smith’s Grove Sanitarium just in time to witness the escape of his monstrous patient, Michael Myers (who’ll be played this time around by Chris Durand, from Class of 1999 II: The Substitute and Uncle Sam). In this revised continuity, Marion stuck with Loomis his whole life long, eventually moving in to become his nurse as his health declined toward the end. The doctor, loyal and generous man that he was, went so far as to leave her the house in his will, and she’s still living there several years later. On the evening of October 29th, 1998, Marion comes home from work to find her porch light smashed and her front door unlocked. No fool, she immediately goes next door to enlist the aid of Jimmy (Joseph Gordon-Levitt, later of Looper and Inception), the neighbors’ brawny teenaged son. Mainly what Marion wants is to use the telephone to call the cops, but you know how adolescent boys are. While his friend, Tony (Branden Williams), stays behind with the nurse, Jimmy grabs his hockey goalie’s stick, and goes to investigate.

What he finds is distinctly odd. There’s nobody in the house, so far as he can tell (although his search is believably less than exhaustive), nor is there any obvious indication of stolen valuables. Nurse Whittington’s office— which is to say, Dr. Loomis’s old office— is thoroughly trashed, however, to the point that nobody except probably Marion herself would be able to tell whether anything were missing. She has a look after Jimmy declares the coast clear, and discovers that one thing has indeed been taken: Dr. Loomis’s patient file for Laurie Strode. If we hadn’t guessed as much already, that would be enough to tell us that Marion’s burglar is none other than Michael Myers, recovered somehow or other from being burned to a crisp twenty years ago, and looking to finish the job of murdering his little sister that he was prevented from accomplishing back then. Also, it happens that Myers is still on the premises, Jimmy’s hasty and haphazard search notwithstanding. He makes short work of both Jimmy and Tony, and although Marion holds him off until the police arrive in response to her earlier summons, the cops don’t come quite fast enough to save her, or to prevent Michael from slipping away. Fortunately, one of the detectives who take over the following morning (Beau Billingslea, of Indecent Behavior III and The Blob) is sufficiently well versed in local history to understand the implications of the crime scene, and calls the police in Haddonfield, the site of Myers’s 1978 Halloween murder spree, to warn them that trouble is coming.

Trouble isn’t coming to Haddonfield, though, because Laurie (Jamie Lee Curtis) doesn’t live there anymore. In fact, so far as the people of her hometown know, Laurie Strode died years ago. However, three quarters of the way across the country, in Summer Glen, California, there lives a woman calling herself Keri Tate whom any member of the Haddonfield High School class of 1979 would find eerily familiar. In some respects, “Keri” is doing quite well for herself these days. She’s the headmistress at the prestigious Hillcrest Academy coed boarding school, she’s got a promising romance brewing with Hillcrest guidance counselor Will Brennan (Adam Arkin, of Lake Placid and Full Moon High), and John, her teenaged son from an earlier relationship (Josh Hartnett, from 30 Days of Night and The Faculty), is growing up into an extraordinarily sturdy and responsible young man. On the other hand, Keri is also an alcoholic, a prodigious consumer of psychoactive medications, a chronic and occasionally acute paranoiac, and a sufferer from recurrent severe nightmares. If she seems remarkably well held together for all that, it’s because John has been doing no small part of the holding. He’s had to mature much faster than is good for him, and two months past his seventeenth birthday, he’s nearing the limit of his own coping ability.

When we drop in on the Tates, the big bone of mother-son contention is the Yellowstone camping trip on which Hillcrest is sending the bulk of its student body for Halloween weekend. John is nearly desperate to do some regular kid stuff for once in his fucking life (to whatever extent any of the scions of privilege at Hillcrest can be deemed regular kids), but if there’s one night of the year on which Keri can’t bear to let her son out of her sight, it’s October 31st. Granted, she saw her brother burn that night after he caught up to her for the second time in the hospital, but the police never found anything identifiable as Michael’s body after the fire was put out. What if he’s still alive after all, biding his time for another go-round, just like he bided it at Smith’s Grove for fifteen years before he broke out? Keri and John spend most of the day arguing in circles around each other, but then the boy learns of some developments that might mean there’s more fun to be had on the nigh-deserted Hillcrest campus this weekend. First, his best friend, Charlie (Diabolique’s Adam Hann-Byrd), is persuaded by his girlfriend, Sarah (Jodi Lyn O’Keefe, from Devil in the Flesh 2 and The Crow: Salvation), to ditch the Yellowstone trip. Sarah went last year, and although she struggles to find words to describe the experience adequately, “lame,” “loathsome,” “wretched,” “boring,” and “repugnant” each capture some aspect of it. And then it turns out that John’s own girlfriend, Molly (Michelle Williams, of Species and Timemaster), won’t be going, either, because her stepfather stiffed the school on her activities fee. So when Keri finally decides that her son has the right of it, and gives him a signed permission slip as he’s leaving the literature class which she teaches, the challenge becomes figuring out how to hide from his mom on campus for an entire weekend.

Or at any rate, that’s what John thinks the challenge will be. But as we well know, the real challenge will be not to get carved into little bitty pieces along with all of his friends by his knife-crazy uncle, who’s spent the last 40 hours or so driving west like a bat out of Hell, guided by the information in that file he stole from Nurse Whittington. The good news is, the Hillcrest campus is walled and gated to at least the same standard of physical security as Smith’s Grove Sanitarium. The bad news is, Michael got out of Smith’s Grove once, and Ronnie (LL Cool J, from Deep Blue Sea and Rollerball), the guard on duty at the gatehouse when Myers makes his move, can’t even be counted on not to let the occasional student sneak out to spend their lunch hour in town. He’s definitely not up to the task of thwarting Michael Myers. Michael’s rematch with Laurie will proceed as scheduled— and this time, there’ll be no meddling psychiatrist to back her up!

It isn’t merely that Halloween H20: Twenty Years Later was the best Halloween sequel to date. At the time of its release, it was also the only worthy one. Previous sequels had their moments, to be sure— especially Halloween 4: The Return of Michael Myers and Halloween 5: The Revenge of Michael Myers— but none of them ever captured the spirit of the first Halloween to any meaningful degree. Halloween H20 does, and I’m inclined to think that has something to do with the lengthy gap separating this movie from the last of its predecessors that it accepts as canonical. As Laurie/Keri herself points out when asked why she still fears her mad brother after all these years, having Michael return to track her down once more after two decades of inactivity neatly parallels the backstory to the first film as modified by the second, and raises the same frighteningly unanswerable question: why now? What goes on in Michael’s head to switch his murderous homing instinct on and off like that? Is it merely a matter of opportunity? Is he responding to some external stimulus to which we’ve never been made privy? Or is it something completely internal and inscrutable— some slow-rolling circadian rhythm of violence that brings out his impulse to murder like an emerging brood of seventeen-year cicadas? There’s simply no telling, and what little evidence we’re given suggests that it’s nothing we’d be able to understand anyway. As I’ve said in other reviews, Michael Myers is scariest when he’s most impervious to explanation. Merely by backtracking to posit that he hasn’t been seen or heard from in twenty years, Halloween H20 makes him bizarre and baffling again. Although the purity of the killer’s original conception remains compromised by the family ties revealed in Halloween II, this is a major step back in the right direction. At the very least, Michael is once again Laurie’s own personal boogeyman.

Even more surprisingly, Halloween H20 somewhat redeems John Carpenter’s long-ago blunder of turning Laurie and Michael into siblings by making their rematch as personal for her as it presumably is for him. When they cross chef’s knives again at last, the battle is for Keri an exorcism of demons that have haunted her for her entire adult life. I don’t think I’ve seen any earlier slasher sequel delve so deeply into the psychological trauma that would surely attend the Final Girl experience in the real world. True, Friday the 13th, Part 2 hints inconclusively in that direction before unceremoniously dispatching Alice in its prologue, while A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors gives Nancy Thompson both a history of psychiatric treatment and a lingering zero-tolerance policy toward her own bad dreams. Still, neither one of those films put nearly this kind of effort into presenting their predecessors’ heroines as emotionally disfigured by what they went through, or portrayed that emotional disfigurement in such realistic detail. Alice’s trauma has only just been established when Jason pops up to avenge his mother. Nancy’s trauma is told rather than shown, and is undercut to some extent by the sci-fi drug she takes to suppress her dreams as an adult. Laurie, in contrast, has faked her death; changed her name; crawled into a bottle; turned her medicine cabinet into a veritable pharmacopeia of downers, uppers, happy pills, and God knows what; tumbled into and out of an ill-advised marriage to a loser as damaged as herself; and pushed her relationship with her son to the brink of ruin with the spillover from her toxic waste dump of a psyche. Only the first of those things feels at all unrealistic, and even it becomes halfway plausible in proportion to the threat that a return visit from Michael would pose. One of Halloween’s most notable features was the astuteness of its character and relationship psychology, so here again, Halloween H20 represents a long-awaited return to form.

The one thing I’m not so thrilled about is just how heavily this movie borrows from Scream, even as I accept that such borrowing was basically inevitable, and recognize that it goes a long way toward accounting for Halloween H20’s vigor and vitality in comparison to the last three and a half films in the series. The cribs from Scream fall into two categories, one of them basically benign, and the other basically malignant. On the upside, Halloween H20 is packed to the gills with conscious and mostly well thought-out allusions to its antecedents, both within its own franchise and within its subgenre as a whole. To some extent, everything I’ve said above about the characterization of Michael and Laurie falls into this category as well, insofar as Scream’s most beneficent influence on slasher movie evolution was its encouragement to think about and to extract meaning from all the tropes that the subgenre had been recycling by reflex action ever since the box office returns for Friday the 13th were first reported. But beyond that, Halloween H20 has a lot of neat details like shots or sequences that deliberately echo moments from the first two films, often deployed so as to comment subliminally on how Laurie/Keri both is and is not the same person as the girl her brother so terrorized back in 1978. Then there’s the relatively minor character of Norma, Keri’s elderly secretary. Norma is played by Janet Leigh, whose pivotal role in the prehistory of the slasher movie should require no explanation— but just in case we need a hint, Norma drives a 1956 Ford exactly like the one in which Marion Crane once fled Los Angeles with a purse full of embezzled cash, and her personal musical cue is one of the subtler possible quotations from Bernard Herman’s old Psycho score. And on an even more meta level, remember that Janet Leigh was Jamie Lee Curtis’s mother. It’s all a bit cheesy, but it’s charming at the same time.

What’s cheesy without being charming, though, is Halloween H20’s tendency to copy very specific plot points and mannerisms from Scream, in a way directly contrary to the deconstructive, interrogatory spirit of that film. I’m talking about too-cute-by-half moments like Sarah’s prediction that John will still be living with his mother long after he grows up, running some creepy motel with her out in the middle of nowhere. I’m talking about the excessive genre-savviness of pretty much every supporting character, together with the limply underexploited implication that the Haddonfield Halloween Murders have become a nationally known urban legend. (Although I suppose the latter is more a lift from other, lesser Scream knockoffs than from Scream itself.) Most of all, I’m talking about the whole opening sequence leading up to Nurse Whittington’s murder, which is built top to bottom out of analogues to Scream’s initial Drew Barrymore fakeout. Obviously none of these crude cribs were enough to stop me from appreciating Halloween H20’s considerable virtues, but they do temporarily get in the way whenever they arise.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact