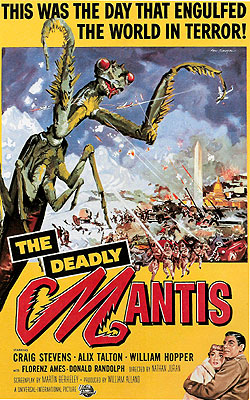

The Deadly Mantis/The Giant Mantis/ The Incredible Praying Mantis (1957) -**

The Deadly Mantis/The Giant Mantis/ The Incredible Praying Mantis (1957) -**

Most of the time, when people talk about Universal Studios monster movies, they’re talking about Dracula, Frankenstein, The Wolf Man, The Mummy-- the “classics” from the 30’s and 40’s and their innumerable sequels. Those with longer memories might mention The Phantom of the Opera as well, but the only 50’s-vintage Universal monster anyone seems to remember these days is the Creature from the Black Lagoon. But there were more Universal monsters in that decade than one lone gill-man-- yes, many more. Not too many realize this today, but the famed purveyor of vampires, werewolves, and stitched-together stiffs was also a major player in the big rubber monster field. And of all the dubious films in the genre to bear the Universal imprint, perhaps none is so eminently worthy of its creators’ shame as The Deadly Mantis.

Bert I. Gordon could, and indeed did on several occasions, do better than this. The movie begins with the camera clumsily panning around a giant wall-map of the world (we can tell it’s “the world” because a caption in the South Pacific helpfully tells us so), coming to rest on a tiny island just above the Antarctic circle just long enough for a narrator (whom we will come to know very well before this is over) to intone, “For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” Then, the screen fills with stock footage of a volcanic eruption, followed by a return to the big map, a pan up to the Arctic, and more stock footage, this time of icebergs being formed. Presumably, the formation of those icebergs is the equal reaction to that volcanic eruption’s action, and presumably it is also opposite because it occurs at the opposite pole. Somehow, I don’t think that’s quite what Newton was talking about. Anyway, next up is a close-up on a praying mantis, frozen in what appears to be a perfectly ordinary (if slightly larger than usual) ice cube, with The Deadly Mantis superimposed on the image in big block capitals. I hope that was a good enough explanation for you of the genesis of our monster, because that’s all you’re going to get.

And now for some more stock footage. In fact, we are about to embark on an utterly incredible seven solid minutes of uninterrupted stock footage while our narrator educates us about the value, placement, and construction of the three “radar fences” that keep vigilant and unceasing watch over the skies above Canada, protecting the American people (except those in Alaska and Hawaii) from nuclear attack by the treacherous forces of international communism. For the next seven minutes, we will thrill to the heroic story of the brave and selfless men who flew to the inhospitable arctic wastes and stayed there for an entire spring and summer to erect this ever-watchful safeguard of our precious freedoms, toiling ceaselessly for the sake of their wives and families thousands of miles to the... ah, skip it. You get the point.

So why, you may ask, do we need a seven-minute stock-footage crash-course on Cold-War electronic early-warning systems? Because those radar fences are about to do a job slightly different from the one for which they were designed, and warn the Free World of attack, not by vast armadas of Tu-95s, but rather by a single colossal bug. First, some unknown force destroys one of the radar installations along the northernmost picket line, taking the station’s crew with it wherever it went afterwards. Then, airplanes begin crashing in the Arctic for no known reason. The only clues are the invariable presence of parallel skid marks in the snow, eight feet wide and a good 80 feet apart, and a mysterious hook-shaped object found in the wreckage of one of the downed aircraft. Colonel Joe Parkman (Craig Stevens, a war-movie regular in the 40’s and 50’s whom anyone reading this is more likely to remember from The Killer Bees), the commanding officer of the northern radar range, takes this strange object and flies to the Pentagon (amid more narration and another great mass of stock footage) to show it to his superior, Major General Mark Ford (Donald Randolph, from The Mad Magician). Ford and Parkman call in the usual bunch of scientists to look at the thing, but all any of them can come up with is that it definitely came from a living organism. One of the scientists then suggests that Parkman should place a call to Dr. Nedrick Jackson (William Hopper, of The Bad Seed, 20 Million Miles to Earth, and-- I shit you not-- Rebel Without a Cause), head paleontologist at the Smithsonian’s Museum of Natural History. Take it from El Santo, if you ever find a piece of some big, weird animal, and the scientist you have take a look at it tells you to call in a paleontologist, you and everyone you know are probably fucked.

So Parkman phones Dr. Jackson, and he is only a little less mystified at the big pointy thing than the previous bunch of white coats. There’s some top-quality bad movie science on display in this scene, most of it attendant on Jackson’s determination that the piece of whatever it is is not made of bone. First, Jackson tells us the hook is cartilaginous in composition. Because we know the barb came from a giant praying mantis (otherwise, the movie would be called The Deadly Gerbil or The Deadly Eggplant or some such thing), we also know Jackson is full of shit-- insects’ bodies are not cartilaginous, they’re chitinous. Big difference-- cartilage is tough but flexible, chitin is hard and stiff, and the two tissues are about as similar, structurally and chemically, as your fingernails are to your liver. Then Jackson outdoes himself with the following exchange of dialogue:

| Jackson: | “Well, we know it can’t be an animal, because every known animal has a bony structure. In fact, the reptile structure is bony-- and, gentlemen, even birds have a bony skeleton.” |

| Gen. Ford: | “Is there anything that doesn’t have a bony skeleton?” |

| Jackson: | “Sure, lots of things. Worms, snails, insects, shellfish...” |

So I guess worms, snails, insects, and shellfish have been re-classified as fungi, huh?

Jackson keeps thinking the matter over when he gets back to the museum, where he fails to keep any secrets from his photographer assistant Marge (Alix Talton, from Rock Around the Clock), who has no real purpose in this movie other than to give Col. Parkman somebody to kiss in the final shot. It is to Marge that Jackson first reveals his ultimate identification of the mystery appendage-- that it is a spur from the foreleg of a praying mantis, a monster mantis which Jackson believes somehow found itself trapped in ice millions of years ago. Nevermind that the age of huge bugs (the Carboniferous period) was a few hundred million years before the first Ice Age, or that even then it could not be said, as Jackson does, that “the smallest bugs were the size of a man.” We need some excuse for this big-ass mantis, and I guess SAC was on vacation that week.

And with the positive identification of the threat, the military can at last spring into action. You know what that means, don’t you? That’s right-- more voice-over narration and more stock footage! At least it’s more interesting stock footage this time (the F-94C has long been my favorite mutant jet fighter of the 50’s), and it doesn’t go on for nearly as long. The predictable scrambling of the fighters meets with the predictable lack of success, and the giant mantis starts flying south, headed for its natural habitat in the tropics (then what in Beelzebub’s name was it doing at the goddamned North Pole?!?!), sinking boats and crashing airplanes as it goes. It takes a brief detour to visit the Washington Monument (it’s a pity monsters don’t have money-- can you imagine how the restaurant business would take off if the giant-monster tourist trade could be fully harnessed?), and then stops for lunch in Laurel, Maryland-- my ex-girlfriend’s home-town, and a mere 20 miles from my house. Then the air force chases it back up north to Newark, New Jersey, where Col. Parkman (do air force colonels really lead aerial intercept missions in person?) has a bit more success shooting the thing down-- he crashes his F-86D into the back of its neck when he fails to notice it flying straight at him in a fog-bank, despite the fact that his plane is a radar-equipped, all-weather interceptor! The creature then takes shelter in the Manhattan Tunnel, where it is finally killed by a bunch of nerve gas bombs.

In a previous review (was it the one for Konga?), I said something about the stultifying documentary-style direction that ruined so many American monster movies in the 1950’s. The Deadly Mantis has a pretty serious case of that particular disease. The heavy load of narration and stock footage that this movie must lug around is probably more than any could bear without damage, and the film’s almost complete lack of concern for the hows and whys of its story doesn’t help matters any. It is also hobbled by extraneous scenes, extraneous characters, and a general lack of urgency. The damn thing is only 78 minutes long, for God’s sake, but it seems to take at least three times that because so little of that time is spent moving the plot along. But it has a really cool, really crappy monster, and ultimately, that’s all that matters. I also found amusing the extent to which The Deadly Mantis is a commercial for the Civilian Observer Corps, the volunteer organization whose job it was to monitor the skies for Russian bombers on their days off. A huge amount of the movie’s stock footage concerns the activities of this bunch, as they hang around on the roofs and balconies of buildings, scanning the horizons for any sign of a praying mantis 150 feet long. In fact, the film’s producers even took the trouble to thank the COC for its cooperation (and for all the stock footage, without which they might actually have had to spend some money on this turkey). All in all, you’re probably better off with Bert I. Gordon and AIP, but The Deadly Mantis is not completely devoid of charm.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact