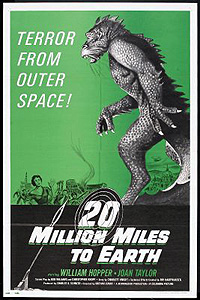

20 Million Miles to Earth/The Beast from Space/The Giant Ymir (1957) ***Ĺ

20 Million Miles to Earth/The Beast from Space/The Giant Ymir (1957) ***Ĺ

Watching Earth vs. the Flying Saucers a little while ago put me in the mood to see a real Ray Harryhausen movieó one in which the famous architectural landmarks get knocked over by a huge, stop-motion monster, rather than by flying saucers with no moving parts. 20 Million Miles to Earth/The Beast from Space/The Giant Ymir seemed like as good a choice as any. Not only is it one of Harryhausen's better known 1950's monster rampage flicks, it also features what was probably his coolest and most convincingly realized monster prior to the gorgon in Clash of the Titans. Itís also a very surprising movie when looked at in context, in that the monster Ymir (which is never identified by name in the movie itself) is portrayed as being nothing more than an animal. An exceptionally tough and intelligent animal to be sure, but Ymir is still a far cry from the virtually indestructible beasts we're accustomed to seeing in movies of this sort.

Our setting is remarkable, too. Instead of the familiar deserts of the American Southwest, 20 Million Miles to Earth takes us to the tiny fishing village of Gerra, on the coast of Sicily. Out on the water on this particular morning are a pair of fishermen named Vericco (George Khoury, from Sabu and the Magic Sword and Abbott and Costello Meet the Mummy) and Mondelo (Wild Womenís Don Orlando) and their pre-teen apprentice, Pepe (Bart Braverman, who would show up many years later in Alligator). Their work is interrupted when an immense aircraft falls out of the sky and into the sea only a few hundred yards away from their fishing flotilla. This is obviously no ordinary jet liner, however. In fact, it looks more like a rocketship with big wings. Realizing that there are almost certainly men trapped in the slowly sinking machine, Vericco rows his boat over to it and takes Mondelo inside with him to look for survivors of the crash. They can find only two before the mysterious vessel goes under. Both men from the rocket are unconscious and injured, one of them quite severely. But because the only doctor in Gerra is busy just now delivering a baby, they would seem to be out of luck. Then Mondelo remembers that a ďdoctor from RomeĒ had come to town recently ďwith his American daughter.Ē Perhaps he could help.

Pepe, meanwhile, has found something very interesting on the beach. Itís a plexiglass cylinder about sixteen inches long and five inches in diameter, marked with a US Air Force insignia. Pepe opens the cylinder, and finds that it contains a translucent, rubbery mass not much smaller than the cylinder itself. When Pepe holds the strange mass up to the light, he realizes that thereís something elseó something organic-lookingó within it, too. Certain that somebody, somewhere would be willing to pay good money for such a peculiar artifact, Pepe wraps the rubbery thing up in his coat and slinks off, careful not to attract the attention of any of the adults on the beach.

Pepe and Mondelo, it turns out, are headed in the same direction. The boy knows something the fisherman does notó that Dr. Leonardo (Frank Puglia, of The Man Who Laughs and The Sword of Ali Baba) is not a medical doctor, but a zoologist. He therefore can't help the two wounded men from the crashed rocket, but his daughter, Mariza (Joan Taylor, from Earth vs. the Flying Saucers), is almost finished with medical school, so there may be something she can do. After Mariza goes off to the beach with Mondelo, Pepe accosts Dr. Leonardo with his unusual find. The boy offers to sell his gelatinous treasure for 200 lire, a sum which seems reasonable enough to the scientist. It doesnít take Leonardo very long after Pepe goes home to figure out that he has absolutely no idea what the strange, translucent mass is.

If he had gone with Mariza, the zoologist would be a little bit closer to finding out. The less seriously injured of her patients is named Colonel Bob Calder (William Hopper, from The Deadly Mantis and Conquest of Space), and he comes to after an hour or so in Marizaís care. Calder immediately springs out of bed and begins frantically interrogating the other crash survivor, whom he identifies as Dr. Sharman (Arthur Space, of Target Earth and Terror at the Red Wolf Inn). Mariza has no clue what they're talking about, but the words ďanimal specimenĒ are mentioned, and Sharman gives Calder a small, black notebook just before he dies. The doctor's death is not at all surprising to Calder; according to him, the unidentifiable disease that was undermining all of Marizaís efforts to treat his wounds had already claimed eight members of his crew. He wonít say what the disease is, or how Sharman and the rest contracted it, however.

The explanation for Calder's reticence lies across the ocean in the Virginia suburbs of Washington DC. At the Pentagon, General McIntosh (Thomas Browne Henry, from The Beginning of the End and The Brain from Planet Arous), and a scientist named Judson Uhl (John Zaremba, of Frankensteinís Daughter and The Magnetic Monster) are dejectedly discussing the apparent last-minute failure of a top-secret mission of space exploration. Their rocket made it most of the way back from wherever it had gone, but then contact was lost while it was flying over the Mediterranean. Over the Med, huh? Well, in that case, McIntosh and Uhl may be interested to hear the incoming news reports that a strange aircraft crashed in the sea off the coast of Sicily. The general and the scientist rush right out the moment word of the crash reaches them. Then in Gerra, at a meeting with the local commissioner of police (Tito Vuolo) and an agent of the Italian government by the name of Contino (Jan Arvan, from The Screaming Woman and Curse of the Faceless Man), McIntosh at last lets us in on whatís really going on. Calderís ship hadnít just gone out into space. The rocketís destination was the planet Venus, which proved to possess a wealth of mineral resources that the US government would just love to get its hands on. Unfortunately, the atmosphere on Venus is so poisonous that not even the best breathing equipment is a match for it. On the theory that studying such a thing would be the best bet for finding a way around that problem, Calderís team was instructed to bring back a specimen of the planetís own animal life.

You guessed it. That thing Pepe sold to Dr. Leonardo is the specimen in question. Itís an egg, as a matter of fact, and by the time Mariza gets home from a long day of caring for the extremely uncooperative Colonel Calder, it has hatched into a more or less humanoid reptile critter a little more than foot tall. Mariza is understandably alarmed to see such a thing walking around on the kitchen table in her fatherís trailer, and her cry brings Dr. Leonardo (who had been in the other room when the egg hatched) running in to see the thing. Awed by the unearthly appearance of the creature in his kitchen, Leonardo quickly grabs it up, takes it outside, and locks it in the cage that occupies the bed of his pickup truck. That settles it; Leonardo and his daughter are going back to Rome tomorrow.

The Leonardosí trip is interrupted in the country just outside of Messina, however. The thing from Venus is growing at a seemingly impossible rate, and itís big enough and strong enough to break out of its cage by the following night, throwing all of the doctorís plans into disarray. The setback gives McIntosh, Uhl, Calder, and the Italian authorities time to catch up to Leonardo, which is a good thing, because itís going to take more than an old man and his not-yet-30-year-old daughter to apprehend the beast. It isnít that the animal is particularly vicious. According to Calder, creatures of this species are actually quite docile unless provoked, and despite their fearsome appearance, their main source of food is raw sulfur rather than the animal flesh one might expect from looking at them. But when the beasts are provoked, they can be very dangerous; theyíre extremely strong and astonishingly resistant to injury. Just about their only weakness, short of massive bodily destruction, is their extreme sensitivity to electrical current. And given that the most likely reaction of the neighborhood peasants to an encounter with the thing would be to shoot at it or sic dogs on it, it can be virtually guaranteed that somebody is going to get themselves hurt or killed if the creature isnít caught soon. With the help of the police (some of it rather grudging), Calder is able to catch the thing before it does too much damage, but thatís small consolation to the one farmer who was nearly killed by it in his barn.

Now seeing as this thing has already broken out of one contrivance intended for its containment, youíd think the lab McIntosh sends it to in Rome (the same one where Leonardo works, as it happens) would take every practicable precaution against its escapeó especially since the creature is now nearly 30 feet tall! But a stupid mishap involving some electrical equipment shorts out the device the scientists were using to keep the beast electrically anesthetized. The Venusian giant wakes up, breaks its bonds, and smashes its way out of the lab. The earlier efforts to catch and/or kill the monster in the Messinian hinterland are now repeated on a much larger scale; all of Rome is now the theater of operations, and the danger posed by the alien is magnified both by the larger population at risk and the creatureís own greatly increased size and strength.

Sometimes thereís nothing quite as satisfying as an old-fashioned monster movie. No message, no deep thoughts, no fascinating character studiesó just a great, big, toothy rubber thing and a bunch of falling scenery. When thatís the sort of mood youíre in, itís hard to do much better than 20 Million Miles to Earth. The movie sets itself apart from the rest of the pack by playing the Sympathetic Monster card, and does it quite well, at that. Itís not the Ymirís fault that itís a menace, after alló it would have been perfectly content to spend its life on Earth hanging out at the sulfur pits of Mount Aetna, never bothering anybody who was smart enough to leave it the hell alone. Itís also just a really impressive monster, and I canít say Iím surprised that Harryhausen would reuse so many of the details of its anatomy in his subsequent creations over the years (compare the Ymirís head to that of the Kraken in Clash of the Titans to get some idea of what Iím talking about here). There are a couple of slip-ups here and there (like the time when we see the creatureís chest rising and falling with breath just a few minutes after being told that it has no lungs), but Iím not inclined to grouse too much about that sort of thing when thereís so much about the Ymir and its movie that is so well done in other respects.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact