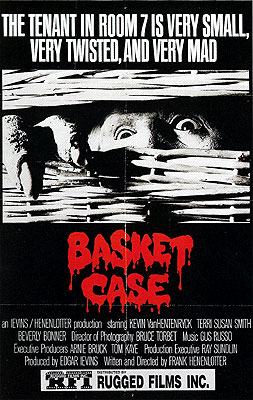

Basket Case (1982) ***½

Basket Case (1982) ***½

In the strange parallel universe of B-movies, one needn’t necessarily be a prolific director to be an important one. Peter Jackson and Sam Raimi, for example, only have a handful of films to their credit, and yet both are big names for that stratum of fandom that considers any movie with the words “zombie,” “cannibal,” or “massacre” in the title a must-see. Frank Hennenlotter is another filmmaker whose significance is all out of proportion to the volume of his output. In fact, when Re-Search tapped him for the opening interview in their Incredibly Strange Films, Hennenlotter had made but a single movie that had seen actual release. That Basket Case alone was enough to elevate its creator to minor stardom should tell you something about the magnitude of the talent at work here.

What Frank Hennenlotter accomplished with Basket Case is that rarest of feats— and one which seems to become rarer with each passing year— the creation of a horror movie that is unlike anything the audience has seen before. Twenty years and two essentially pointless sequels later, it’s easy to lose track of this, but in 1982, Basket Case was little short of revolutionary. That its seamless melding of slasher, vendetta, monster-rampage, and Cronenbergian medical horror elements had never been attempted before (that I know of, at any rate) is impressive enough. That the passage of time has also proven it nearly impossible to emulate is outright shocking. Walk into the horror section of any video store in the country, and you’ll be hard pressed to turn around without bumping into half a dozen clones of Halloween, Psycho, Night of the Living Dead, Jaws, or Alien, but when have you ever encountered a quickie Basket Case knock-off? Yeah. That’s about what I thought.

The movie begins with the murder of a surgeon named Dr. Lifflander (Bill Freeman) by a brutal, unseen assailant. Someone has staked out the doctor’s house, and is lying in wait when he returns from somewhere or other late at night. The killer makes a few stealthy noises to clue the victim in to his presence, cuts the phone lines, and then sneaks up on Lifflander while he futilely tries to dial 911. The doctor hasn’t got much left in the way of a face by the time the killer is through with him.

Elsewhere, in the grimy, sleazy, degenerate Times Square of the early 80’s (and has any filmmaker ever conveyed this particular subspecies of urban squalor as convincingly as Hennenlotter does here?), a young man named Duane Bradley (Kevin Van Hentenryck) checks into a room in an especially grubby hotel. Duane’s only luggage consists of a backpack and a large wicker basket, so he makes an unusual enough impression on the hotel manager (Robert Vogel) even before he pays for the room by peeling a couple of twenties off of a startlingly fat wad of cash. Imagine what the manager and his circle of regular customers would think if they could see Duane up in his room, talking to whatever is in his basket, and feeding it prodigious quantities of hamburgers from the greasy spoon across the street!

The next day, Duane takes his basket to the office of Dr. Harold Needleman (Lloyd Pace). He doesn’t have an appointment, but Needleman’s receptionist, Sharon (Terri Susan Smith), is perfectly willing to accommodate him, on the grounds that it’s a slow afternoon, and there are scarcely any patients scheduled to come in. Duane ominously signs in under an assumed name, offering the excuse that Needleman is an old friend of the family, and Duane doesn’t want to spoil the surprise of his visit by tipping the doctor off on the sign-in sheet. Needleman doesn’t seem to know who Duane is at first, but when the boy takes off his shirt and reveals the ghastly scar that covers the entirety of his right flank, a flash of troubled recognition steals across the doctor’s face. On his way out of the office, Duane makes a date with Sharon for the following afternoon, so that she can show him around New York.

That evening finds Duane eating dinner with another doctor, a certain Judith Kutter (Diane Brown— oh, and by the way... Dr. Kutter? Dr. Needleman?). The meal is interrupted by a telephone call from Needleman, who apparently knows Dr. Kutter from some nasty business involving Duane many years ago. So nasty, in fact, that Kutter hangs up on Dr. Needleman, telling him that neither one of them ever knew a Duane Bradley, or each other either, for that matter. She then returns to the dining room and her guest, whom she now remembers having met before.

Those viewers with sharp eyes will have noticed that Duane’s basket is not in evidence over at Kutter’s place. That’s because it’s at Needleman’s office instead, as the unfortunate doctor is about to discover. Needleman finds it while he is closing up for the night, and when he opens it up, its occupant, a misshapen lump of a creature about as big as the top half of a man’s torso, with a pair of stumpy, heavily muscled arms, but no legs at all, reaches out and grabs him. The hideous thing lays into the doctor with tooth and nail, and leaves him in about the same condition as Dr. Lifflander.

Hints at the connection between Duane and the thing in the basket begin to emerge the next day, when Duane is out seeing Sharon. There appears to be some kind of telepathic link between the boy and the monster, and when the latter senses that its companion is making time with a girl, it flies off the handle and starts noisily wrecking the hotel room. The commotion brings nearly every one of the other residents running, but when the manager uses his key to open up the room, there is no sign of who or what caused all of the ruckus, and Duane’s basket is empty. One of the hotel’s regulars (Joe Clarke) follows the manager into the room, though, and this sharp-eyed old weasel notices Duane’s money lying unguarded on top of the dresser. He arranges to be the last person to leave Duane’s room, and when he does so, it is with the cash in his pocket. But the thief won’t have long to enjoy his ill-gotten gains, because when he stops at the bathroom on the way back to his room, the basket monster is waiting for him. It carves him up just like the doctors, and relieves him of the stolen funds.

But murders cannot long go unnoticed, even in a flea-pit hotel in one of New York’s sleaziest neighborhoods, and when Duane returns from his date, he finds a police detective (Kerry Ruff) poking around in his room, on the plausible theory that whoever trashed it probably cut up the old man, too. The basket monster is a sneaky little bastard, though, and has done a marvelous job of covering its tracks. The cop is forced to go back to the station empty-handed.

By this time, you’re probably really starting to wonder just what the hell is going on here, and Hennenlotter apparently agrees that the time has come to lay all the cards out on the table. The night after the thief’s murder, Duane heads out to a bar to get really, seriously shitfaced for the first time in his life. At the bar, he runs into another resident of his hotel, a stylish black woman who isn’t quite attractive enough to justify her unfortunate habit of dressing like a girl fifteen years her junior, by the name of Casey (Beverly Bonner, whom Hennenlotter liked enough to use again in both Brain Damage and Frankenhooker). With more alcohol than he has ever seen before in his system, Duane gets talkative, and spills the whole story to Casey. The thing in the basket is named Belial, and it is— are you ready for this?— Duane’s twin brother! Indeed, Duane and Belial were Siamese twins, the huge scar on the normal brother’s side marking the place where his deformed twin was originally attached. Their mother died giving birth to them, and their father (played in the accompanying flashback by Richard Pierce) never forgave Belial for “killing” her. When the twins were perhaps twelve years old, their father hired a team of surgeons— Lifflander, Needleman, and Kutter— to separate them. This had to be done at home, and strictly under the table, because Mr. Bradley’s intentions were to leave Belial to die after the operation was completed. The mutant boy proved tougher than anyone expected, however, and after being rescued from the dumpster by Duane, survived to avenge himself on his filicidal father. The murder, in which Duane acted as Belial’s accomplice, was engineered so that it could just barely be passed off as an accident with the unnecessarily large circular saw Bradley kept in the basement, and the boys’ aunt (Ruth Neuman), who knew full well what her brother-in-law was up to, raised them from then on. And as you’ve probably figured out by now (though Duane wisely leaves this part out of his confession to Casey), Duane and Belial have spent the years since their aunt’s death on the trail of the doctors who separated them, with the aim of completing the revenge that began with the murder of their father.

But now Duane has a problem. He told Casey the story of his childhood within earshot of the basket, and while he may have been drunk, Belial was not, and the mutant has his head screwed tightly enough onto what passes for his shoulders to recognize the hassles that Duane’s little gab-fest could cause them. They still have one more doctor to kill, after all, and it just wouldn’t do for Casey to jeopardize the mission in a moment of indiscretion. Not only that, Belial has grown very jealous of Duane’s budding relationship with Sharon. If you’re beginning to get the feeling that a conventionally happy ending just isn’t in the cards here, you’re probably right.

It pains me to say it, but I really don’t think very many horror fans under the age of 25 are going to have much patience with Basket Case today. The years since its initial release have seen a precipitous drop in the cost of the Tom Savini-Stan Winston school of special effects, and even the cheapest direct-to-video trash usually boasts more convincing gore and monster effects than this movie. The tiny budget with which Hennenlotter was saddled ($50,000 before the expense of blowing the negative up to 35mm from 16 ballooned the total cost up to $160,000— of which only $7000 were actually on hand when shooting began!) is immediately evident, and forced distasteful compromises on the director at every stage of production. Beyond the obvious technical difficulties (often unconvincing makeup and effects, poor picture and sound quality, etc.), the stiff financial limitations frequently forced Hennenlotter to accept imperfect takes of scenes he would surely have re-shot if he had been able to afford the film on which to do it, and to rely on a cast with literally zero acting experience. Unavoidable though they were, these things mean that the viewer has to cut Basket Case a great deal of slack before he or she can fully appreciate Hennenlotter’s surprisingly self-assured direction and brilliantly demented script. There are two important ways in which the movie’s limitations work in its favor, though. First, the almost total lack of technical gloss helps to bring home the filth and grime of the film’s setting; no Hollywood movie could ever match the authentic slum ambience of Basket Case. And second, Kevin Van Hentenryck’s stilted performance as Duane is exactly what the role calls for. It would take an actor of considerable talent to simulate the stiffness and discomfort that Duane exhibits in all of his social interactions as convincingly as Van Hentenryck’s very real stiffness and discomfort in front of the camera does. Basket Case is unquestionably a flawed gem, but it is a gem nevertheless.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact