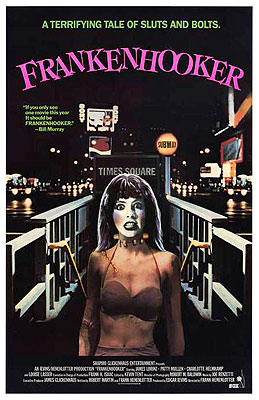

Frankenhooker (1990) ***½

Frankenhooker (1990) ***½

While talking to Andrea Juno in 1986 for Re/Search #10: Incredibly Strange Films, Frank Henenlotter said of his attitude toward screenwriting, “I’m sitting there cackling as I’m typing: if I get money out of this one, wow.” There’s no movie about which I find that easier to believe than Frankenhooker. The contours of its mad plot were extemporized by Henenlotter at a meeting with James Glickenhaus, of Shapiro-Glickenhaus Entertainment, the production company that had backed Brain Damage a few years before. Henenlotter had actually come to pitch a script called Insect City, but Glickenhaus deemed that project too unmanageably bizarre even for his company to sell successfully. (Incidentally, just try to imagine a screenplay weird enough to provoke a reaction like, “Nah, I don’t think we can use that— but let’s make Frankenhooker instead!” Unfortunately, imagining it is all we can do, because Henenlotter never seems to talk about Insect City except in the context of Frankenhooker’s origins. He and Glickenhaus are probably the only people alive with any real idea what the film was supposed to be.) When the producer asked him if he had anything else in the works, Henenlotter pulled a grindhouse Frankenstein riff straight out of his ass, and just kept talking for as long as Glickenhaus kept laughing. Then he got together with Robert Martin (the founding editor of Fangoria, who had left the magazine not long before, and was looking for new creative outlets) to discipline that chaotic improv routine into a viable script. The movie that eventually resulted is both one of the last pure products of New York City’s independent sleazoid filmmaking tradition, and a deathbed portrait of the environment that made it possible for such a tradition to arise in the first place.

Jeffrey Franken (James Lorinz, from Street Trash and The Transfiguration) is not, strictly speaking, a mad scientist, or even a mad doctor. Although his mother (Louise Lassen, of Blood Rage) talked him into attending three different medical schools in the years since he graduated from college, Jeffrey got thrown out of all of them, and finally wound up as a power plant repairman for the New Jersey Gas and Electric Company. It happens, though, that Franken’s downward mobility has been the best thing imaginable for his officially discontinued studies, because the gig with the power company has opened up to him an entire domain of knowledge and skills which he’d never previously considered. By combining what he’s learned on the job with what he’d already learned in school, Jeffrey is developing a new field of scientific endeavor, which he calls “electrobiology.” For some idea of what Franken means by that, consider what he’s working on the first time we see him: a brain with a single eye installed between the halves of its prefrontal cortex, capable of acting as a voice-controlled remote television camera. Franken himself has no clear idea what if any practical use there might be for such a thing. Right now, he’s just exploring the possibilities inherent in combining surgery with electrical engineering.

In any case, Jeffrey needs to knock off tinkering with his braincam for the afternoon, because his fiancée, Elizabeth Shelley (Doom Asylum’s Patty Mullen), is throwing a birthday party for her dad (J.J. Clark) out in the backyard, and her mom (Joanne Ritchie) needs to use the kitchen table. They’re all out of dipping veggies out there, and she wants to chop up some more carrots, peppers, and cauliflower florets. Besides, Elizabeth just cut the cake, which means it’s almost time for her to unveil Mr. Shelley’s present from his daughter and presumptive son-in-law, itself a product of Jeffrey’s mechanical talents. He’s built the old man a new lawnmower— and not just any lawnmower, either, but a high-speed, high-powered, remote-controlled model, so that Mr. Shelley will be able to give all the grass on his property the perfect suburban buzzcut from the shade and comfort of his own porch. Alas, Elizabeth is so excited about the machine that she pays no attention to where she’s standing when she fires it up to demonstrate its capabilities. The mower drives straight over her at full speed, chopping her into about a thousand pieces.

Franken is a quick thinker, though, and in the confusion following the accident, he manages to gather up the most intact of those pieces—including, most importantly, Elizabeth’s nearly undamaged head. After all, maybe electrobiology can do for her what conventional medicine cannot, at least once Jeffrey has his techniques and technology further refined. In the meantime, there’s a great, big, coffin-style freezer in the garage, which should suffice to keep the salvageable parts from rotting. Next, Franken turns his attention to a more permanent means of preservation, ultimately concocting a viscous, purple fluid based on estrogen and human blood, capable of sustaining what’s left of Elizabeth indefinitely. A plan for the actual repairs soon follows, in the form of an intricate wiring diagram scrawled onto a life-sized anatomical drawing of the female form. Then, as the penultimate step, Jeffrey begins smuggling equipment home from the power plant, installing it in his garage piece by piece until he’s got a lab worthy of any Frankenstein, Jekyll, or Moreau. There’s an important sense in which all of these preparations remain idle exercises in theory, however. The lawnmower and the police medical examiner between them left nothing like a complete body for Jeffrey to reconstruct, so he’s stuck unless and until he can figure out what to do about all the missing parts.

The answer, appropriately enough, itself comes to Franken in pieces. First, while trepanning himself with an electric drill to focus his thoughts (a technique on which Jeffrey has come increasingly to depend since he discovered it), he realizes that every single night, the streets of Manhattan’s skuzzier neighborhoods turn into a vast, open-air market for high-quality female flesh. It’s just that when those girls speak of selling their bodies, they generally envision a more temporary transaction than the one Jeffrey has in mind. An initial reconnaissance foray into the city (check out what Tribeca looked like at the turn of the 90’s!) brings Franken into contact with two promising-looking prostitutes by the names of Honey (Charlotte J. Helmkamp, of Posed for Murder and Repossessed) and Amber (Kimberly Taylor, from Beauty School and Bedroom Eyes II), together with their pimp, Zorro (Joseph Gonzalez, who also appeared briefly but conspicuously in Brain Damage). Franken invents a plausible-sounding story about wanting to recruit a few hookers for his nonexistent brother’s supposedly upcoming birthday party, and makes an appointment to examine all seven members of Zorro’s stable to ensure that he chooses the very best. It’s during the negotiations for that deal that the second element of Franken’s body-harvesting plan— how exactly to divest his unwitting donors of the parts that he requires— falls into place. Every single one of Zorro’s whores is hooked on crack cocaine, which the pimp exploits to keep them tractable and obedient. Jeffrey, too, will exploit their addiction by concocting supercrack, an almost instantly lethal variant that causes the user to explode mere moments after inhalation.

Jeffrey, to his small credit, gets cold feet at the crucial moment. Sure, he keeps his appointment with Honey, Amber, and the rest of Zorro’s stable at the fleapit hotel where they generally do their business. Sure, he meticulously measures, tabulates and assesses every square inch of all their bodies, earning in the process the sobriquet “Dr. Jersey Boy.” He even gets as far as selecting the prime donors for all the parts that Elizabeth is currently missing. But in the final assessment, Jeffrey simply isn’t a murderer, and he eventually finds himself trying to back out of the whole undertaking, almost against his own will. The hookers, naturally, don’t realize what a reprieve they’re being offered. They see only a major moneymaking opportunity slipping away from them after the fruitless investment of enough time for them all to have sold a blowjob or two apiece. Furious at being stiffed, Honey seizes Dr. Jersey Boy’s medical satchel to rifle it for cash, and thereby discovers his jar of supercrack. Once the whores see that, there’s simply no keeping them away from it, and Jeffrey winds up with seven whole bodies’ worth of assorted girl parts, whether he wants them anymore or not. Meanwhile, Zorro gets testy about how long it’s taking Franken to make up his mind. He drops in just in time to see the last of his hookers explode, and is knocked out cold by Honey’s head as it goes flying across the room. The pimp’s arrival (and his temporary incapacitation) seems to get Jeffrey motivated again to do what he came here for. Bagging up all the disassembled prostitutes, he tosses them down the fire escape to his waiting car, and makes his getaway before Zorro regains consciousness.

This wouldn’t be a Frankenstein movie, though, would it, if the resurrection of Elizabeth went according to plan? All things considered, Jeffrey’s rebuild of his fiancée is very impressive on the physical front (although it was admittedly a curious choice to incorporate parts from donors of three different races, so that she ends up with one black forearm and an Asian ass). But when she descends alive again from the thunderstorm into which Jeffrey had hoisted her up to catch the invigorating lightning, the reconstituted Elizabeth isn’t exactly herself anymore. Indeed, to the extent that she can be said to have a personality at all, it seems to consist of disintegrated fragments carried over from Zorro’s hookers, all of them trapped in some loop of memory from their final hours of individual life. And when Jeffrey responds to her demand for money with a bewildered refusal, the new Elizabeth slugs him with all the superhuman strength that we’ve come to expect of Frankenstein monsters, putting him out like a light. By the time Jeffrey comes to, Elizabeth is back downtown, stumbling awkwardly through the motions of her reconstructed body’s former profession, and raising absolute hell while she’s at it. Fortunately, it doesn’t take Franken long to grasp what went wrong, but bringing Elizabeth home for an upgrade and a system reset is going to be easier said than done. Also, Jeffrey really ought to look in the freezer where he stashed all the surplus hooker bits after he was done making his girlfriend’s new chassis. It caught a lot of spillover from the lightning-driven power surge that activated Elizabeth, and some very interesting things are happening in there as a consequence.

Although most of Frankenhooker’s numerous allusions are obviously to Frankenstein in one interpretation or another, there’s an important sense in which this is also Henenlotter’s take on The Brain that Wouldn’t Die. We’re clearly supposed to recognize it as such, too, because Jeffrey’s braincam— a closeup on which is the very first image we see— is based on a creature that was invented for The Brain that Wouldn’t Die’s advertising art, even though nothing like it appeared in the film itself. Both movies concern medical mavericks who turn their girlfriends into monsters in a misguided attempt to undo some fatal accident for which they feel responsible, without reference to the desires of the women in question. And in both films, the plan for restoring the dead woman requires the murder of one or more living ones— with the same bulllshit justification invoked, whether implicitly or explicitly, by both monster-makers. Jeffrey Franken and Bill Cortner alike intend to draw their raw materials from the bodies of women who were already commodifying them in some way, excusing the crime by telling themselves that there’s no meaningful difference between hiring a whore and stripping one for parts. The cultural environment of 1959 was such that The Brain that Wouldn’t Die had to substitute strippers, artists’ models, and beauty pageant contestants for prostitutes per se, but Frankenhooker had the freedom to forego such euphemism 30 years later.

Henenlotter has always claimed not to think about the subtext to his movies, let alone to deliberately build messages and morals into them, and I think I believe him. But that doesn’t mean nothing ever bubbles up from his subconscious while he’s making a film, and the differences between Frankenhooker and The Brain that Wouldn’t Die are even more revealing than the similarities from that perspective. Note that Franken is both more and less culpable than Cortner, depending upon which aspect of his activities we examine. On the one hand, Cortner never quite gets around to murdering any of his candidates for the supplier of Jan’s new body, and the only people killed by either of his monsters are his assistant and himself. It takes seven dead hookers to make one live Elizabeth, however, and the resurrected girl’s demented ramble through Tribeca racks up quite a body count before Jeffrey catches up to her. At the same time, though, Franken carries considerably less blame than Cortner for the accident that sets the whole sordid affair in motion. Bill was driving like a goddamned lunatic when he rolled his car down that hillside and decapitated Jan, but all Jeffrey did was to forget the safety bumper when he built a lawnmower for his future father-in-law. Also, he’s in the process of aborting his plan for mass meretricide when Zorro’s girls take the decision out of his hands by seizing and smoking his supercrack. In both cases, then, Jeffrey’s female victims deliver the actual killing stroke themselves, for all that he provides them with the wherewithal to do so. Consequently, one might argue that whereas Bill Cortner is a figure of malign hubris, Jeffrey Franken is more just recklessly irresponsible— not that it makes a lot of difference in the end, so far as the women in their lives are concerned.

It’s worth keeping all that in mind, too, when considering the bad end to which Jeffrey inevitably comes. The canonical mad scientist (Bill Cortner included) is destroyed by the monster he creates, but Franken is resurrected by his monster after Zorro catches up to him to avenge his exploded whores. A mulligan for death might not sound like a bad end at first, but remember that Jeffrey’s biorestorative formula is estrogen-based. It doesn’t work on male bodies, so in order to bring him back, Elizabeth has to draw from his freezer full of leftover hooker parts (or at any rate, from the ones that are still usable after being fused together into this movie’s counterpart to The Brain that Wouldn’t Die’s Closet Monster). Franken, in other words, is about to get a little lesson in empathy regarding the way he treats women. It’s not only more creative than the traditional approach, but more poetically just as well, while managing to be simultaneously a subtler form of comeuppance and a more outrageous one. Instead of dying for his meddling in the workings of nature, Jeffrey and Elizabeth alike get to live with its consequences as best they can.

It should be obvious already that a lot of what separates Frankenhooker from, say, your typical late-80’s Troma pickup is simply the cracked brilliance of Frank Henenlotter. But at least equally important are the performances of James Lorinz and Patty Mullen, each of whom brings a seemingly impossible level of genuine sensitivity to an absurdly broad characterization, while displaying at the same time an impressive gift for comedy. Jeffrey’s evolution from “extreme weirdo, but still basically sane” to “complete fucking nutcase” is a bigger acting challenge than it might seem at first glance, because it starts with him already far beyond the pale of socially acceptable behavior. How the hell does one get loopier than “tinkering with a homemade brain monster at the kitchen table in the midst of your father-in-law’s birthday party” while still holding everything to a recognizably calibrated progression? Mullen is the real MVP here, however. For all practical purposes, she has to play three different characters, but doesn’t get a lot to work with for developing any of them. The sunny, lovestruck, slightly ditzy Elizabeth from before the accident and the subtly embittered Mk II Frankenhooker, who seems to be taking just a little too much pleasure at Jeffrey’s discomfiture upon his transsexual resurrection, have only a couple scenes each in which to put themselves across, and the severely defective Mk I Frankenhooker isn’t even capable of speech beyond the jumbled and out-of-context recitation of her constituent whores’ dialogue from earlier in the film. Nevertheless, Mullen succeeds brilliantly in all three of her character’s incarnations— especially Frankenhooker Mk I. From her uncoordinated, spasmodic walk to the distant, glazed look in her eyes to her staccato delivery of her recycled lines, she’s just unstintingly delightful. And there’s this thing she does with her mouth whenever her brain misfires from all the conflicting half-thoughts that simply beggars description; I don’t know how she does it (heaven knows I can’t make my face do anything comparable), but you’ll know it when you see it. It frankly astounds me that Frankenhooker didn’t turn Mullen into something like the other Barbara Crampton— a cult exploitation starlet whose willingness to do nudity is a bonus on top of her acting ability, instead of the other way around. Instead, though, she drifted out of the movie business very quickly after this film’s release, and made a perfectly ordinary and respectable life for herself down in Florida. I hate to begrudge anybody living out their desires, but I do wish we’d gotten at least a few more extraordinary and disreputable movies out of her first.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact