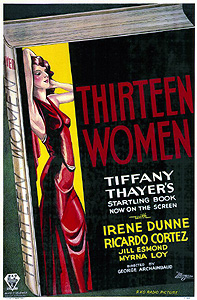

Thirteen Women (1932) **½

Thirteen Women (1932) **½

It came as quite a shock when I first recognized the parallels between the body-count mysteries of the 30’s and 40’s and the slasher films of my own youth, not least because fans of the former typically expressed nothing but scorn for the latter. Throughout my teens and early 20’s, I simply accepted at face value the standard line asserting that horror and suspense movies in the good old days would never have lowered themselves to the kind of subject matter that dominated the genre in the 80’s— which is to say, the kind of subject matter that I really liked— and so I was content to ignore the likes of Phantom Ship and A Study in Scarlet just as their fans were mostly content to ignore The Burning and Don’t Go in the Woods Alone. But around the time that I started writing these reviews, I began to take a more historical approach to the movies I watched, seeking to learn about them instead of merely to be entertained. That led me to begin watching movies I didn’t expect to like, and although I can’t say I’ve acquired more than a rudimentary taste for the films that gave my grandparents the willies, I have found them an engrossing intellectual exercise. The more attention I paid to the old stuff, the more fascinated I became by the continuities I observed across the decades, even between such outwardly dissimilar films as The Old Dark House and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Thirteen Women, a largely forgotten body-counter from RKO, is an especially striking example of such continuities. In it, the women of the title are preyed upon by someone they collaborated to wrong in their schoolgirl days, who has returned years later to engineer their deaths and downfalls, one by one by one.

Among the performers at the Joe E. Marvel Circus are the Raskob sisters, May (Harriet Hagman) and June (The Phantom of Crestwood’s Mary Duncan). The Raskobs are aerialists, and June seems to be getting cold feet about their act. As she explains when her old friend, Hazel Cousins (Pat Entwistle), comes to visit her backstage before she and May go on, she’s become extremely worried about a letter she recently received by mail. Some time ago, June, May, Hazel, and nine other women who had belonged to the same sorority when they were in finishing school together all wrote to an astrologer named Swami Yogadachi (Kongo’s C. Henry Gordon), asking to have their horoscopes cast. Yogadachi’s reply to June apologetically predicts that someone close to her is fated to die by her hand. Most of the twelve former classmates— June among them— regarded the horoscope thing as nothing but a lark, but with this alarming forecast, June finds herself unable to disbelieve fully, especially considering that she and her sister literally place their lives in each other’s hands every time they go to work. Hazel assures June that she’s getting worked up over nothing, but during the Raskobs’ performance that afternoon, June fails to catch May in the middle of their flying double flip trick. The sisters always work without a net in public, and true to Yogadachi’s horoscopic prediction, May does not survive the drop. June checks into a mental hospital shortly thereafter.

It’s rather curious, then, that when Yogadachi hears the news about the acrobats, it plunges him into a panic over the possibility that he is losing his ability to interpret the stars. Wasn’t May’s fall exactly what the swami predicted? Evidently not. As Yogadachi laments to his lover, Ursula Georgi (Myrna Loy, from The Mask of Fu Manchu and It Happened at Lakewood Manor), he saw great happiness and prosperity in the Raskob girls’ futures, just as he has for Hazel Cousins (whose horoscope he has not yet sent out). So if that’s true, then who wrote the letter that June was fretting over when she accidentally killed her sister? Would you believe it was Ursula? Not only that, but Ursula has her own version of Hazel’s forecast, warning that she is destined to wind up in prison. As soon as Yogadachi goes to bed, Ursula tears up his letter to Hazel and substitutes her own. Sure enough, just days after receiving the doctored horoscope, Hazel has an altercation with her husband, an altercation that gets rather out of hand. Without really knowing what she’s doing or why, she picks up a kitchen knife and stabs her spouse to death.

It turns out that similarly ominous missives have by now gone out to all the old school friends, eliciting a wide array of reactions. Grace Combs (Florence Eldridge), a believer in all things hogwashy, embraces her seemingly certain undoing with a rapturously masochistic fatalism, and counsels the other women to do the same. Helen Frye (Kay Johnson), who has been prophesied to take her own life— and not implausibly, given the depression that has weighed on her since the accidental death of her son a year or so ago— starts carrying her husband’s loaded pistol around everywhere she goes, spitting in the face of her supposed destiny by making sure she is never without the means to fulfill it. Jo Turner (Jill Esmond, of F.P. 1 Doesn’t Answer) laughs the whole thing off, but with an unmistakable air of repressed uncertainty. The only one we see (more on that later) who rejects the doom-laden horoscopes like she really means it is Laura Stanhope (Irene Dunne). Apparently seeking to counteract the panic that Grace has been sowing with her exhortations to bow before the dictates of the heavens, Laura invites everyone with whom she keeps in touch over to her place for a nice, normal sorority reunion. Even when Helen shoots herself as foretold on the train ride to Laura’s, even when Yogadachi himself dies beneath the wheels of a different train after writing to Grace that the stars have finally decreed his own demise, Laura refuses to believe that astral influences have anything to do with her friends’ misfortunes. Then Laura gets her horoscope letter, and recognizes at once that somebody is out to get her and her remaining friends. The letter predicts that her son, Bobby (Wally Albright), will die on or shortly before July 1st, which happens to be his birthday.

Sergeant Barry Clive (Ricardo Cortez, from The Sorrows of Satan and The Walking Dead), the detective who examines the scene of Helen’s death for signs of foul play, doesn’t buy any of that astrology crap, either. True, he rules Helen’s death a clear suicide, but when he and his men bring her luggage and personal effects to Laura’s house (having ascertained that that was where the dead woman was headed), and he learns about June, May, Hazel, Yogadachi, and the letter threatening Bobby, Clive starts thinking he smells a conspiracy. He’s right, of course, but that conspiracy is closer to hand than anybody realizes. Laura’s chauffeur, Burns (Edward Pawley), has succumbed like Yogadachi to Ursula’s charms, and that birthday the kid has coming up provides an excellent cover under which to sneak packages containing things like poisoned candy and booby-trapped toys into the Stanhope house.

At this point, we know the who, what, and how of Ursula’s campaign of extermination, but not the why. Well, our first clue is the slightly sallow complexion and subtle fake epicanthic folds that the makeup people have applied to Myrna Loy’s face. Despite her unplaceably European name, Ursula Georgi hails originally from India (although Ursula’s appearance would make more sense if screenwriters Bartlett Cormack and Samuel Ornitz actually meant Nepal instead), the child of one white parent and one native. At some point in her adolescence, she fell under the influence of a missionary who hoped to Westernize her by, among other things, sending her to the nice, respectable school where she met up with Laura and the others. That was where the trouble started. It didn’t take Ursula too long to figure out that she’d get nowhere by emphasizing the Asiatic half of her heritage, but the other girls at the school would not accept her as one of their own race, either, no matter how good her English, and no matter how faint the traces of otherness in her features. The details never quite come out in the version of Thirteen Women that survives today (more on that later, too), but the gist of it seems to be that Ursula attempted to join a prestigious sorority at some point, but received nothing but mockery and humiliation for her efforts. The women whom Ursula now terrorizes and destroys were once the girls who thwarted her efforts to rise above her station. Up to now, it has sufficed for her to use the power of suggestion against her victims, playing upon their insecurities to make them bring about their own ruination, but Laura has no gullibilities or neuroses to exploit. Thus the shift to more hands-on tactics— and with them, a far greater risk of being exposed and brought to justice.

You will notice that I mentioned substantially fewer than the promised thirteen women in the forgoing synopsis. So does the film itself. When Thirteen Women was initially released, it ran 73 minutes, and was regarded by its studio as a rather modest A-picture. It bombed at the box office, though, and RKO swiftly pulled it out of circulation for some major editing surgery. Thirteen Women lost fully fourteen minutes of footage, and made its second round of the theaters demoted to supporting-feature status. Apparently it was no more successful in that capacity, because it was again withdrawn after a short run, rarely to be seen again. I’ve been able to find no detailed description of what was cut out, but it’s clear enough that the vanished footage at least partly concerned the fates of Ursula’s other victims, none of whom are so much as named in the present version (unless you want to count the nearly illegible portrait captions in the yearbook that the killer is shown perusing early on). From my point of view especially, Thirteen Women’s fragmentary state renders any assessment of its merits somewhat provisional. What’s most wrong with the movie is its insufficient emphasis on the scope and effectiveness of Ursula’s vengeance campaign, and it appears that the excised footage would have squarely addressed that complaint. An extra murder or seven would almost certainly have quickened the pace a little, too, and Thirteen Women’s tendency to lollygag is my second-biggest objection. Indeed, the one major defect that a restoration to the original running time would obviously not help is the unfortunate synergy between the lumpy dialogue and the excessively prim acting of the principal players, which often gives the impression that Thirteen Women takes place in a world populated by Blade Runner’s replicants— and not the fancy new Nexus 6 models, either!

Even the seriously flawed truncated version retains a few significant points of interest to set it apart from the numerous similar films that were released during its decade, though. Most obviously, there’s Laura Stanhope’s role in the story. She isn’t quite a Final Girl in the modern sense, but she’s damned close to it, especially when Ursula finally takes matters into her own hands and comes for her and Bobby directly on the overnight train to New York whereby they hope to escape from her. (Incidentally, I note that nearly every description of Thirteen Women to be found on the internet says that Ursula chases Laura through the train, carrying a knife. I don’t know where the writers of those synopses got that from, because nothing like it ever happens. Rather, Ursula hypnotizes Laura to give herself an opening to kill Bobby in his sleep, and it’s Barry Clive who ends up chasing Ursula.) Also of note are Ursula’s weapons of choice, her talent for hypnosis (which she implicitly gets from the Indian/Nepalese/whatever side of the family) and the suggestibility of her victims’ minds. There’s no destiny at work here, not really. June Raskob fails to catch May because she’s too busy worrying about not catching her to do it. Helen Frye shoots herself because Ursula, having planted the idea in her head via the supposed letter from Yogadachi, contrives to meet her in person, and subtly reminds her of how depressed she really is. Yogadachi falls in front of the subway partly because he has Ursula standing next to him with her serpent stare, willing him to do it, and partly because he accepts to begin with the astrological principles underlying her earlier prediction that he would die that way. Only when she comes up against someone sufficiently clear-headed and strong-willed to be impervious to her deadliest tricks does she resort to conventional criminal techniques, and the moment she does so is the beginning of the end for her. Finally, there’s the matter of Ursula’s motive. Seriously, how many 1930’s genre movies can you think of that even imply a disapproval of racism, let alone make resentment of and backlash against it the driving force of the plot? Of course, there’s a certain hypocrisy to the way that theme is handled here, since the makers of Thirteen Women cast the very white Myrna Loy and C. Henry Gordon as its Asians, but to see the subject raised at all in a film of this vintage is shocking. You kind of have to wonder if maybe that might be the reason why Thirteen Women was so resoundingly unpopular at the time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact