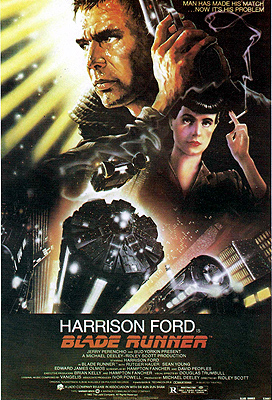

Blade Runner (1982/1991) ****½

Blade Runner (1982/1991) ****½

I have to wonder which Hellgod Ridley Scott sold his soul to in 1978 or thereabouts. I mean, within five years of making the jump from television to feature films, Scott had directed two of the best and most influential science fiction movies of his era, without simultaneously generating the torrent of crap which Sturgeon’s Law would seem to require. Being that good and that lucky at the same time scarcely seems possible. Nor did Scott repeat himself to any meaningful extent in pulling this trick off, following up Alien, an ingeniously effective update of the 50’s-style space-monster flick, with Blade Runner, a similarly inspired futuristic reinvention of the late-40’s film noir detective drama. At first glance, it might seem that Blade Runner has not been ripped off as extensively as its predecessor, but when you factor anime into the equation, it becomes much tougher to make that call. (The enthusiasm with which the Japanese have copied Blade Runner is only to be expected— large sections of Tokyo already look like Blade Runner’s Los Angeles, except clean and almost comically free of street crime.) It offered a thinking man’s dystopia to stand in counterpoint to the vast horde of contemporary Road Warrior knockoffs. And like Alien, Blade Runner had a marked elevating effect on the careers of its leading performers, bolstering Harrison Ford’s claim to the status of serious actor while almost single-handedly securing Rutger Hauer’s reputation as the scariest Teuton since Klaus Kinski.

Blade Runner also earns distinction for being, in all probability, the most impressive adaptation of a Philip K. Dick story yet filmed. Though it diverges quite shamelessly from the plot of Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and adopts a tone so different from the novel’s as to be nearly antithetical, Blade Runner absolutely nails the more interesting of the book’s parallel themes, the question of what humanity might mean in a world of thinking— and potentially feeling— machines. As Dick himself is reputed to have said, it’s not exactly his story, but it’s a damn good one, and it’s light years ahead of such later Dick adaptations as Total Recall and Screamers.

The year is 2019, and from the look of things, humanity has managed to pollute at least Southern California, and probably the rest of the world as well, into pretty dire straits. Birth defects and congenital diseases are widespread, the air is so full of crud you can actually see it, it rains almost constantly, and wild animals of all species (except, apparently, for pigeons) are practically extinct. Fortunately, space travel has become a sustainable commercial enterprise, and offworld colonies have sprung up wherever local atmospheric and terrestrial conditions are minimally hospitable to human life. Those who can afford to leave the moribund Earth do so, and the mass exodus has led to strange pockets of depopulation even in otherwise crowded cities and fueled the rise of a brand new industry. The hazards of space colonization being what they are, it is only to be expected that robots would be employed extensively to do the hard work, and because the consumers apparently prefer their artificial companions to be as human-like as possible, the main trend in android design has been toward ever-increasing mimicry of natural human beings. The Tyrell Corporation is at the forefront of the industry, and their latest model, the Nexus 6 Replicant, is practically indistinguishable from a real person, although the Replicants greatly exceed human capabilities in terms of strength, speed, agility, reaction time, and overall hardiness. It would appear, however, that the law requires some basis for drawing a distinction between those who were born and those who were manufactured, and so Tyrell’s genetic designers have engineered a four-year lifespan into their Replicants, ensuring that the androids will not have sufficient time in which to develop the full range of human feelings. Furthermore, in the wake of a Replicant uprising on one of the colony worlds, the humanoid machines were declared illegal on the home planet, and special police agencies called Blade Runner units were instituted to hunt down and destroy any androids that made their way to Earth in contravention of the new law.

Holden (Morgan Paull, from The Swarm and Uncle Sam) is a member of one such unit, operating out of Los Angeles. He was sent to Tyrell headquarters after the stolen shuttle on which six Replicants returned to Earth turned up in the ocean not far from L. A. Holden’s superiors suspect that the androids may seek to infiltrate the company that created them, and so he has been dispatched to screen the latest crop of Tyrell employees using the Voigt-Kampf test, which measures the physiological changes that accompany emotional response; because Replicants’ emotions are so poorly developed, the Voigt-Kampf is supposed to be able to distinguish between humans and androids. One of the new guys Holden is to take a look at is garbage man Leon Kowalski (Brion James, of Flesh & Blood and Steel Dawn). Kowalski is one of the renegade androids, and he guns Holden down the moment he figures out that he’s on the fast track to failing the test.

Elsewhere in the city, retired Blade Runner Rick Deckard (Harrison Ford, from Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark) is having dinner at a sushi stand when a policeman named Gaff (Edward James Olmos, from Wolfen and Virus) threatens to arrest him if he doesn’t come talk to his old boss, Captain Bryant (M. Emmet Walsh, of Escape from the Planet of the Apes and Sundown: The Vampire in Retreat). Bryant wants Deckard to come back to work; he was the best Blade Runner the captain ever had under his command, and after what happened to Holden, Bryant figures no one but Deckard will have what it takes to “retire” the fugitive Replicants. Threats eventually succeed where persuasion fails (one gets the impression that the police in 21st-century Los Angeles are effectively a law unto themselves, with no meaningful checks on their behavior— not too far from how things really turned out, now that I think about it…), and Deckard takes the job, with Gaff assigned to him as a subordinate partner.

The first order of business is to show Deckard exactly who he’s supposed to be looking for. One of the six fugitives died trying to penetrate the electrical field that serves as a security perimeter around the Tyrell complex, leaving Deckard with four targets to track down. (We’ll discuss the implications of this obviously cracked arithmetic a bit later.) Leon Kowalski we already know about. Of the others, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer, of Bleeders and The Hitcher) is presumed to be the leader; he was designed to be a soldier, and possesses the greatest strength, dexterity, and intelligence of the bunch. Zhora (Joanna Cassidy, from The Glove and Ghosts of Mars) is another military model, whom Bryant tantalizingly identifies as having been “trained for an offworld kick-murder squad,” whatever the hell that means. The forth Replicant is Pris (Daryl Hannah, who also appeared in The Fury and The Final Terror back before anybody had ever heard of her), an android prostitute of the sort which is generally employed in the licensed brothels of colonial military bases. Any one of them is more than a match for Deckard physically, so he’s going to have to rely on a sharp eye, a quick wit, and a big gun.

As further preparation for his mission, Deckard heads over to Tyrell headquarters, where Dr. Eldon Tyrell (Joe Turkel, from Tormented and The Dark Side of the Moon) will allow him to administer the Voigt-Kampf test to a Nexus 6— presumably that model wasn’t yet in service when Deckard was last active on the force. Deckard is greeted by a young woman named Rachel (Dune’s Sean Young), who visibly resents his occupation. At first, Deckard doesn’t understand why Tyrell insists on having him administer the test to Rachel before trying it out on a Replicant, but eventually it dawns on him that Rachel herself is a Nexus 6. In fact, she’s an experimental second-generation model, equipped with a lifetime’s worth of implanted memories borrowed from her creator’s niece. She’s so close to human that even she doesn’t know she’s a robot. The rationale behind the experiment is that reports from the field indicate that ordinary Nexus 6’s frequently do develop considerable emotional capacities even despite their short lifespans, but of a strangely stunted and unhealthy type. Tyrell believes that by giving the Replicants enough implanted memories for them to mistake themselves for humans, he and his engineers can eliminate or at least minimize the tendency of the androids to become obsessive, violent, and chronically depressed around the beginning of their third years. The one contingency which Tyrell’s scheme hasn’t addressed is the possibility of Rachel figuring out somehow what she really is— perhaps as a result of some cop coming along and making her take a Voigt-Kampf test, for example. As a matter of fact, it would appear that Rachel is eavesdropping on the conversation between Deckard and her designer, because she will later follow the Blade Runner to his apartment in an effort to get a straight answer regarding her humanity or simulation thereof.

As it stands now, Deckard really has only one lead, the address which Leon gave Holden during his Voigt-Kampf examination. He and Gaff go to check the place out, and while they’re there, Deckard finds two curious clues. The first is a scale which he turns up in the bathtub; the second is the collection of photographs— mostly a random assortment of family snapshots— which Leon kept stashed in his dresser. After the aforementioned painful scene with Rachel, Deckard notices that three of Leon’s pictures are slightly different perspectives on the same scene, and reasoning that these must have been taken by the Replicant himself, he feeds one of them into an electronic enhancer to see if he can squeeze any more clues out of it. Under enhancement, the picture reveals a mirror on the wall in which a reflection of Zhora can be seen, dressed in a spangly outfit of the sort you might expect a stripper to wear. A trip to the Chinatown bazaar where the city’s makers of artificial animals keep their shops reveals that the scale came from a synthetic snake, and when Deckard interviews its maker, he learns that the buyer of the snake was the owner of a high-priced showbar. And sure enough, when Deckard goes to the bar, who should he see doing a striptease with an artificial python but Zhora the Replicant. Zhora almost throttles Deckard with his own necktie before he is able to take her out, but take her out he does. Unfortunately, Leon sees him do it, and Deckard has another close brush with death before Rachel unexpectedly comes to his rescue, shooting the other Replicant in the head from behind.

Deckard isn’t the only one conducting an investigation, though. The Replicants’ business on Earth is to arrange an audience with Eldon Tyrell in the hope that he can somehow extend their lifespans, and under Roy’s leadership, they appear to have found someone close enough to the boss to give them their in. Tyrell’s eyeball engineer (James Hong, from The Satan Bug and Big Trouble in Little China)— under considerable duress, of course— tells them where to find J. F. Sebastian (William Sanderson, of Nightmares and Sometimes They Come Back), the top genetic designer in the company, and Pris slyly befriends him in the guise of a runaway orphan. Sebastian isn’t just an employee of Tyrell’s; he’s also the boss-man’s friend and regular chess partner, and Batty uses the ongoing game between the two scientists as a pretext upon which to gain access to Tyrell’s penthouse apartment. But Tyrell has nothing to say to Roy that the Replicant wants to hear. Imparting more life to a Replicant after it has been completed is a biochemical impossibility, and Roy and his rapidly shrinking circle of refugees are doomed despite their best efforts. In a rage, Roy kills both Tyrell and Sebastian, then returns to the huge, derelict apartment tower where the geneticist had been living. He gets there just a little while after Rick Deckard (who was tipped off by Bryant after the discovery of Sebastian’s body), and the battle is joined.

One notable point about Blade Runner’s influence which often gets lost in the discussion of its artistic merits is that (at least so far as I can remember) it was the first film to be reissued years after its initial release in a director’s cut, so called. These days, even a porno movie might get a director’s cut if the circumstances are right, but until 1991, it was essentially unheard of for a studio’s leadership not to reserve the final say on the final cut to themselves. Earlier movies had circulated in alternate edits, to be sure, but in virtually all cases, it was a question of the producers’ preferred cut vs. what the MPAA or the relevant local, state, or national censorship authorities would allow on the rating the studio heads desired. The difference between what a studio released and what a director intended was an esoteric matter— something for obsessive fans to grumble about and for frustrated filmmakers to rail against. It took the extraordinary combination of clout, ego, and willingness to make a pest of himself which Ridley Scott had attained by the early 90’s to open the door to the director’s cut as we know it, and it took the legendary status of Blade Runner (together with the much-discussed nature of the changes ordered by the studio) to turn a one-shot deal aimed substantially at shutting Scott up into a profitable venture, and to make the present studio cut/director’s cut dichotomy an economically sustainable phenomenon. That being the case, it’s rather surprising in retrospect how similar the two cuts of Blade Runner really are. The director’s cut eliminates the voiceover narration by Harrison Ford which, in the first-run version, filled the bulk of the silences in most of the scenes which unfold from Rick Deckard’s point of view. It cuts the tacked-on, upbeat resolution in which Deckard and Rachel leave Los Angeles for the comparatively unspoiled country to the north in favor of a sudden, in-media-res ending, which leaves open the question of what sort of future those two embattled characters may expect. It removes a pair of well-done but arguably gratuitous gore effects, one attendant upon Eldon Tyrell’s death and the other involving the nail with which Roy Batty skewers the hand that keeps seizing up on him during his climactic showdown with the Blade Runner. And in what seems at first to be a pointless, inexplicable indulgence, it adds a brief sequence in which a drunken Deckard dreams about a unicorn trotting through a forest.

The two most obvious differences— the variant endings and the voiceover narration— have, to my mind, opposing effects on the film. Though I can understand why many fans (and Ridley Scott, too, for that matter) dislike the voiceover, I think it adds a great deal to the film. Yes, the specific content of some of the lines is grating, in that it implies that someone involved in the movie’s creation didn’t trust the audience to figure out, for example, that “skinjob” is a derogatory term for Replicants, or that the hotel room which Deckard and Gaff search is the one where Leon told Holden he was living. It also undeniably distracts from the subtler visual aspects of certain shots, as when Deckard is contemplating the dead Roy Batty on the roof of the Bradbury apartment complex, and Gaff’s flying squad car can be seen coming in for a landing over the Replicant’s shoulder, just barely in focus. But we’re talking about film noir here, and in the stereotypical film noir, the detective at the center of the story keeps up a virtually continuous voiceover monologue, commenting upon even the most obvious aspects of the action onscreen. The narration in the first-run version completes the sensation that you’re watching the 21st-century adventures of Philip Marlowe, and so far as I’m concerned, it’s absolutely vital to the feel of the movie. On the other hand, I’m in agreement with seemingly just about everyone that the more ambiguous ending is superior. Not that the long ending is offensive, mind you, but it ties the story up a little too neatly for a movie which up to then had gone out of its way to make as many things problematic as possible. And since the ending which Scott originally wanted doesn’t explicitly rule out a happily-ever-after for Deckard and Rachel, I really can’t understand the complaints of the test audiences who apparently considered it an intolerable downer. What I’d really like to see is a version that retains the voiceover, but ditches the oversweet coda— oh, and I want those two gore clips, too, just ‘cause I’m an uncouth barbarian.

Now let’s talk about that unicorn. Ever since Blade Runner first appeared, observant viewers have been arguing over whether or not Rick Deckard was supposed to have been a Replicant himself. Even the original theatrical version contains plenty of subtle clues to that effect. Like the Replicants he hunts, Deckard keeps a collection of photos which have no apparent connection to his own life. He is as emotionally flattened as any android, and at one point, Rachel asks him bitterly whether he had ever taken the Voigt-Kampf test himself. And in what might be the most important clue, Bryant tells Deckard that there were six Replicants in the rebel band at first, but that the accidental death of one of them leaves Deckard with only four to bring down. Any first-grader could tell you that there’s an android unaccounted for there, and the threat from Bryant that convinces Deckard to sign back on makes a lot more sense if we postulate that Deckard himself is the Replicant in question, and thus liable for execution under the law. That would also explain why Bryant gets in touch with Deckard by having Gaff arrest him. These days, Ridley Scott is on record as saying that Deckard is a robot, and that business with the unicorn is supposed to be the evidence that proves it. Here’s how it works: Everywhere Gaff goes, he leaves little origami figures behind him— a chicken in Bryant’s office, a little man with a gargantuan cock in Leon’s hotel room, etc.— and at the end of the film, Deckard finds an origami unicorn in his flat, and knows thereby that Gaff paid it a visit while he was at the Bradbury; his aim, presumably, had been to retire Rachel, yet unaccountably he chose not to do so. We’re supposed to read the fact that Gaff left Deckard a unicorn in particular the same way we read it when Deckard earlier confronted Rachel with some of the memories that were downloaded into her brain from Tyrell’s niece, to conclude that Gaff knows Deckard dreams about unicorns because at some point, he talked to the person who programmed Deckard’s brain. Purportedly, Scott had wanted to include the dream sequence in the original cut, but had to drop it from the shooting schedule because of time constraints.

Whether it’s the case or not that Scott meant Deckard to be a Replicant from the get-go (the evidence is somewhat inconclusive), I’m glad he left the matter so vague (and thus easy to discount and dismiss), even in the director’s cut. Simply put, it weakens the film tremendously if Deckard isn’t human. For one thing, it makes mincemeat of Blade Runner’s thematic thrust by removing the central irony that Deckard, the natural-born man, is infinitely colder and deader inside than even Leon, the most brutal and debased of the Replicants. It also undercuts the intensely moving scene on the roof of the Bradbury between the beaten Deckard and the dying Roy. But worse yet, if Deckard is a Replicant, then the movie makes no logical sense. Remember— Rachel is an experimental prototype, a Nexus 6.1, so to speak. If Deckard is an android, he obviously doesn’t know it himself, yet the technology that makes Rachel’s lack of self-awareness possible has only just been introduced; under the terms which the rest of the story has established, there’s no way for Deckard not to know what he is. In the novel, the implantation of false memories in androids is a routine practice, but we have been explicitly told that that isn’t the case in the world of the film. We might also ask how, if Deckard possesses Replicant strength and agility, a scrawny little sex-bot like Pris has such an easy time beating his ass in hand-to-hand combat. Meanwhile, if we assume, as Scott subtly invites us to, that Deckard is the unaccounted-for sixth hijacker, then why doesn’t he remember being in on the caper, and why the hell don’t any of the other Replicants recognize him?!?! It’s ridiculous, and given the choice between concluding that Blade Runner is ridiculous and concluding that the ridiculousness lies only in one misguided interpretation of it, I’m going to go with the latter, no matter what Ridley Scott has to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact