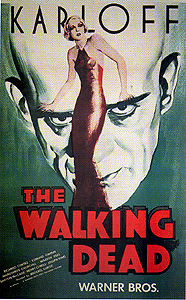

The Walking Dead (1936) ***

The Walking Dead (1936) ***

Back in the days when the major studios still had distinct individual personalities, Warner Brothers caused something of a stir by producing, throughout the 1930’s, a string of crime melodramas that depicted the American justice system as hopelessly dysfunctional, rife with incompetence at best and even more corrupt than the criminals from which it was supposed to protect society at worst. It was therefore more or less logical that Warner would be the first Hollywood studio to experiment with combining elements from the crime and horror genres. The Walking Dead, which was released at the tail-end of the first major Hollywood horror boom, is noteworthy not just for its pioneer status, but for its successful execution of that most difficult of tricks, the melding of two genres which offer no guiding precedent for how they might be combined.

The setup is typical of Warner’s pessimistic 30’s crime films. Racketeer Stephen Martin (Kenneth Harlan, from The Corpse Vanishes) is on trial, and the case against him is air-tight, but all of the more informed spectators are nevertheless certain that the accused will leave the courtroom a free man. Not only is his lawyer, Nolan (Ricardo Cortez, from Thirteen Women and The Sorrows of Satan), a well-connected member of the same criminal organization as Martin, it is widely (and correctly) believed that the judge in the case has been receiving calls from Martin’s mob threatening violence against his wife and daughter. But even in the Warner Brothers universe, there are still a handful of incorruptible men, and this judge is one of them. Stephen Martin is sent up for ten years, with the judge publicly proclaiming his wish that the statutes under which Martin was convicted provided for more severe punishment.

Obviously, the mob doesn’t like this. Mob boss Loder (Barton MacLane, from Cry of the Werewolf and The Mummy’s Ghost) is used to getting his own way from the courts, and he, Nolan, and his other top associates, Merritt (The Mad Monster’s Robert Strange) and Blackstone (The Gorilla’s Paul Harvey), believe it necessary that an example be made of this judge who has the temerity to apply the law with honesty and integrity. Loder brings in his best enforcer, Trigger Smith (Joe Sawyer, who went on to appear in Them! and It Came from Outer Space), to bring the situation under control. Trigger’s plan shows that he’s well worth whatever Loder is paying him. It just so happens that a certain John Elman (Boris Karloff), who has been serving a ten-year sentence for second-degree murder, has just been released from prison, and has gotten in touch with the Loder mob in the hope that someone in it might be able to help him find a job— perhaps somebody owns a club that could use an accomplished piano player? This is a golden opportunity, because Elman was tried by the same judge that passed sentence on Martin, and is thus the perfect decoy with which to distract the police once Trigger rubs out the judge. Posing as a private detective, Trigger approaches Elman with an offer of respectable money in exchange for assistance in keeping tabs on the judge, whose wife (or so Trigger says) believes he may be having an affair on the side. All Elman has to do is hang around near the judge’s place after dark, taking notes on his comings and goings; Trigger himself (or so he implies) will be working the day shift. Of course, what’ll really happen is that Elman— who has a plausible enough motive for murder— will be observed staking out the judge’s house night after night, compiling a circumstantially incriminating record of his movements. And just to make the charge stick that much better, Trigger and his men dump the judge’s body in the back seat of Elman’s car after performing the hit. It would be difficult for any man to be much more fucked than Elman is right now.

There’s one little detail Trigger didn’t plan for, however— there are two witnesses to his disposal of the body. Jimmy (Night Key’s Warren Hull) and Nancy (Marguerite Churchill, of Dracula’s Daughter), assistants to medical researcher Dr. Evan Beaumont (Edmund Gwenn, another familiar face from Them!, who was in Bewitched as well), accidentally stumbled upon the scene on their way back to Beaumont’s place after a night out on the town. (There’s some indication that Nancy is Beaumont’s daughter, but their relationship is never made entirely clear.) Trigger dutifully threatened the couple to get lost and keep quiet once he realized what they had seen, but the two witnesses nevertheless stuck around long enough to encounter Elman as he walked back to his car with his notes for the night. When Elman goes to trial (with Nolan as his lawyer, deliberately aiming to lose the case so as to cover his colleagues’ asses), he continually asserts not only that he is innocent, but that an unidentified man and woman told him they saw several other men deposit the victim’s body in the back seat of his car. Of course, Nolan has no real interest in finding these two exculpatory witnesses, and so Jimmy and Nancy learn that they hold the power to save Elman from the electric chair only after it’s too late to help him at the trial. Even then, Nancy is reluctant to come forward, fearful that Trigger and his men will, as promised, come after them if they say anything. Dr. Beaumont is made of sterner stuff, however, and once Nancy and Jimmy tell him what they know, he insists that they call Elman’s lawyer and tell him what they saw.

Nolan, as you might imagine, isn’t pleased to hear from Beaumont and his assistants. But even so, circumstances demand that he at least make a show of trying to save his client, so he dilly-dallies his way over to the office of District Attorney Werner (Henry O’Neill), and then dilly-dallies his way over to Beaumont’s place to interview the witnesses. Werner is convinced that Jimmy and Nancy’s testimony is at least strong enough to merit a stay of execution for Elman, and he places a call to the governor, requesting a pardon. The governor agrees, but by the time the cops working the front desk at the prison answer his phone call reprieving Elman, the man has already been given his first jolt from the chair.

This is where Dr. Beaumont comes in. He has been working on a technique for reviving dead organs for use in transplant operations, and has enjoyed a considerable amount of success in his endeavors. In fact, he thinks his process might be effective enough to revive entire organisms, though he has yet to test that hypothesis. Well, with the demonstrably innocent Elman now dead because the evidence that could have saved him was never admitted into court, Beaumont figures he’s in a position to further his research and correct a grave injustice at the same time. The script understandably doesn’t go into detail on this, but somehow, Beaumont convinces the authorities to let him try to revive Elman, and soon enough, the dead man is lying strapped to a gurney in the scientist’s lab, while huge electrical machines pump gigantic sparks into him. (Anyone who starts having Frankenstein flashbacks at this point is to be forgiven— Beaumont even shouts, “He’s alive!” when Elman opens his eyes!)

Clearly, this means trouble for the Loder mob. Granted, Elman claims not to remember anything from before he was brought back to life, but the information is most definitely still in his brain somewhere; if he can still play piano like a pro, there’s no reason he shouldn’t eventually remember everything. In fact, it isn’t too long before hints start appearing that Elman remembers, at least subconsciously, things he never even knew in the first place! The first indication comes when he meets Nolan for the first time after his resurrection. Despite the fact that Nolan has just won him half a million dollars (half a million 1936 dollars, mind you) by suing the state for wrongful death, Elman exhibits an intense loathing for the man, and even goes so far as to tell Beaumont and Nancy that “that man is my enemy.” This gets DA Werner (who has been spending a lot of time with Beaumont ever since their meeting on the night of Elman’s execution) thinking. Werner knows, even if he couldn’t prove it in court, that Nolan has mob connections, and he has some idea which of Nolan’s friends are part of the same racket. It is Werner’s suspicion that Elman somehow knows that Nolan had something to do with framing him for murder. What Werner wants to do is try to engineer a meeting between Elman and the other members of the Loder mob; if Elman has the same sort of intense irrational reaction to the rest of them as he does to Nolan, Werner will have some idea who the judge’s real killers were. Sure, it wouldn’t hold up in court, but Werner would at least know whom to keep an eye on.

Actually, Werner might not have to worry about what a trial judge will and will not allow. Elman’s new status as an international medical curiosity has kept him rather busy with press conferences and the like, and when Werner gets Beaumont to invite Nolan, Loder, Merritt, and Blackstone to the next one, the living dead man takes the same preternatural dislike to all four of them. And what’s more, something wakes Elman up in the middle of the night soon afterward, and leads him to pay a visit to Trigger Smith. Trigger is understandably alarmed by seeing Elman show up at his apartment, and he gets so worked up that he trips over a piece of furniture while backing away from Elman with a loaded pistol in his hand; the gun goes off when Trigger hits the floor, killing him. And by a fortuitous coincidence, Merritt happens to be on his way over to Trigger’s with instructions for him to re-kill Elman. The target of these orders is still in the building when Merritt arrives, and this gangster, too, is so terror-stricken by the resurrected man that he blunders into a lethal accident, falling to his death from Trigger’s open window. Over the next several days, the rest of Loder’s men will have run-ins with John Elman that lead directly to their accidental deaths. It’s as though some supernatural force were using the returned man as an instrument for balancing the cosmic scales of justice. The question is, what’s going to become of Elman once he gets around to Loder himself, and his otherworldly mission is complete?

The Walking Dead is a vast improvement over the more straightforward horror movies Warner Brothers made earlier in the decade. With horror films no longer the huge moneymakers they had been a few years before, there was less temptation to favor spectacle at the expense of story, and The Walking Dead is mercifully free of distracting gimmicks like Technicolor and celebrity comic relief. What it offers instead is a seamless fusion of gritty crime drama and thoughtful, sci-fi influenced horror. The elements are combined much more skillfully here than they would be in Black Friday, Universal’s somewhat later foray into the same territory (which, interestingly enough, also featured Boris Karloff in a central role). And of equal importance, The Walking Dead’s component parts are of rather higher intrinsic quality. When it came to gangster movies in the 1930’s, Warner Brothers were arguably the best in the business, and this film’s horror elements are also much more sophisticated than was typical in its day. The idea that God would allow a wronged man’s temporary resurrection in order to use him to bring the real evildoers to justice is a fascinating departure from the kind of premises that underlie most horror flicks of this vintage, and I’m particularly impressed with the degree of care that this movie’s creators took to present it in a convincing, internally consistent way. Note, for example, that John Elman never actually kills anybody; all of his “victims” kill themselves in panic-induced accidents when Elman comes for them. Given that John is being used as an instrument of divine justice, it is morally necessary that his hands remain clean of blood— even of blood that deserves to be spilled. Otherwise, Elman really would be a killer, mitigating, on the cosmic scale at least, the injustice of what was done to him. Few screenwriters working for the majors today would ever show this level of concern for the philosophical underpinnings of a story— a modern remake would have John Elman (who would be played by somebody like Jean Claude Van Damme or, heaven help us, Wesley Snipes) bopping on down to the corner gun shop immediately after his return to life, where he would buy up enough firepower to enable him to take on your average Central American military with a fair chance of success, and then spend the next hour machine-gunning his way up the mob hierarchy to Loder and Nolan (who would be played by John Travolta and Gary Oldman). As anyone who’s been reading my reviews for a while surely knows, I’m no knee-jerk partisan of old-timey films, but I’ll say one thing for them: in the 1930’s, no one had yet thought of the cinematic maxim, “When in doubt, just blow shit up.”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact