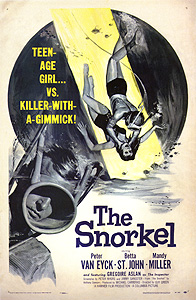

The Snorkel (1958) ***

The Snorkel (1958) ***

Before the emergence of horror as the studio’s main product line in the mid-1950’s, Hammer Film Productions enjoyed a more modest but still notable success with a string of noir-inspired crime and suspense thrillers. Those movies were distinct from the “mini-Hitchcocks” of the following decade, but that isn’t to say that the two cycles were unrelated. Indeed, there’s at least one film that fits almost equally well into either category. As is perhaps to be expected, The Snorkel was Jimmy Sangster’s contribution to the earlier program. It was his first feature-length screenplay for Hammer, as well as one of the last suspense movies the company would release before Scream of Fear and its successors rendered the distinction between that genre and horror largely meaningless in Hammer practice. The Snorkel tells a story that could easily have served as the basis for a mini-Hitchcock, but it does so in a much more linear and streamlined way, without all the twists and realignments— which makes sense, since the mini-Hitchcocks borrowed those tactics from Psycho, and that movie was still years in the future in 1958.

Writer Paul Decker (Peter Van Eyck, from The Brain and The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse) is killing his wife. So far as the rest of the world is concerned, he’s away in southeastern France, working in seclusion on his latest book, but tonight he has stealthily returned to the family villa just over the border on the Italian coast to fake Madge’s suicide. It’s a clever arrangement, if also a very risky one. (Indeed, it wouldn’t work at all in the real world without some minor tweaking, given the limits of human lung capacity. It needs either a much shorter hose or some tanks of compressed air.) The villa was never wired for electricity, and its second-story sitting room is full of gas lighting fixtures. After apparently drugging Madge and tape-sealing all the doors and windows from the inside, Paul dons a diving snorkel linked by rubber hoses to a chink in the outside wall below the level of the floorboards. Then he retreats below the floor himself, into a secret crawlspace which he presumably prepared for just this purpose. When the housekeepers arrive in the morning, it looks as though Madge has taken her own life. Even the inspector from the local police department (Gregoire Aslan, from The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and Blood Relations) sees no reason to suspect foul play, and when Paul emerges from hiding after all the hubbub has died down, he is in complete control of his late wife’s sizable fortune, unencumbered by the attendant inconvenience of the woman herself.

Actually, Madge’s murder was but the culmination of a much longer game. When Paul met and befriended her however long ago that was, Madge was married to a man by the name of Brown. It was love at first sight— in the sense that Decker was instantly enamored of the Browns’ money, and began scheming from a very early date to appropriate it for his own use. Having ingratiated himself to the couple, Decker arranged for Brown to die in what the rest of the world remembers as a boating accident, and then got to work on winning Madge’s broken heart. We already know how that turned out, of course.

There’s just one slight flaw in this otherwise perfect crime. The Browns had a daughter named Candy (The Man in the White Suit’s Mandy Miller), and she saw Paul drown her father while pretending to attempt his rescue. Nobody believed her at the time, dismissing her as just a hysterical little kid, but now Candy is well into her teens. She has neither forgotten nor forgiven, and when she and her governess, Jean Edwards (Betta St. John, from Corridors of Blood and Horror Hotel), cut short a sojourn abroad in response to the news of Madge’s death, the first thing Candy tells anyone who’ll listen is that Paul is somehow behind the tragedy. It’s the “anyone who’ll listen” part that gives the girl trouble. Both Jean and a friend of the family called Wilson (William Franklyn, of Enemy from Space and The Satanic Rites of Dracula) vividly recall her earlier tales of her father’s drowning, and basically just go, “Oh, not this again…” when she starts pointing the finger at Paul anew. But the inspector doesn’t believe Candy is delusional. It’s simply that he can’t think of any way for Decker to have contrived the circumstances that confronted him at the villa this morning. Paul couldn’t have left the room after turning on the gas, but neither was he anywhere to be found when the cops arrived on the scene. And even if he did have some well-concealed hiding place, surely he couldn’t have gassed Madge to death without also gassing himself, right?

At this point, The Snorkel essentially turns into the darkest Nancy Drew mystery ever, as Candy and her faithful spaniel, Toto, snoop for proof that her stepfather murdered both her parents. Meanwhile, Paul endeavors to convince Jean that Candy is cracking up, so that the governess will support him in a bid to have Candy committed to an asylum, and thereby neutralized. Candy gathers all the pieces to the puzzle surprisingly quickly, but she fails for a time to understand that she’s done so, or to see how they fit together. Paul, however, sees very clearly how close the girl is to the truth. With so much at stake, the madhouse won’t be good enough anymore. Decker will just have to kill his stepdaughter, too.

As I said, this could easily have been a mini-Hitchcock. Just like in Scream of Fear and Nightmare, it has a high-strung girl at the mercy of an evil relative. It has a Gaslight-like campaign to persuade the outside world that the heroine is out of her mind. It has concerned outsiders who would have no trouble coming to said heroine’s rescue, if only they weren’t so thoroughly duped by the villain’s plot. And it plays very rough with Candy, albeit not nearly as rough as Sangster’s later, more overtly horrific thrillers would with her various successors. Indeed, The Snorkel rather resembles Night of the Hunter with regard to the gravity and immediacy of the danger in which it places its young protagonist, but unlike that movie, this one gives the impression that the filmmakers genuinely might not allow the imperiled kid to emerge unscathed. The Snorkel also outdoes Night of the Hunter on the grounds of plausibility. Peter Van Eyck plays Paul Decker as someone whom no one would suspect of such terrible evil, which is vital to a story in which nobody but the underdog heroine ever does.

But at the same time, The Snorkel is just as interesting for how it isn’t like the mini-Hitchcocks. Viewers accustomed to those films will spend the whole of this one anticipating plot twists that never materialize. For example, I kept expecting to learn that Jean was in on the conspiracy, or at the very least that she and Paul were having an affair that would lead her to turn a blind eye to his crimes, but no. Jean is misguided certainly, and her unfairness to Candy comes very close to getting the girl killed, but she is honestly taken in by Decker’s deceptions. Similarly, I kept waiting for Wilson to emerge as Candy’s rescuer, but in the end, the kid is left to her own devices— which is actually much more satisfying, anyway. On the other hand, that ending goes in a rather more benign direction than I was prepared for on the basis of the events leading immediately up to it, and that’s not so satisfying. The Snorkel sets up a conclusion as perfectly wicked as any to be found in 60’s psycho-horror, but backs down from the blackest possibilities at the last moment. Next to Mandy Miller’s irritatingly shrill performance, that backing down is my biggest gripe with this picture. It isn’t really a fair complaint, though. This was only 1958, and what The Snorkel retreats from is a 1965 ending at the earliest.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact