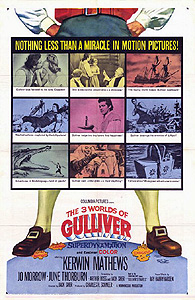

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960) **

The 3 Worlds of Gulliver (1960) **

Jonathan Swift was one of the greatest satirists that the British Isles ever produced, and his most famous novel, Gulliver’s Travels, was a scathing indictment of the folly and strife that characterized Western European religion and politics during his era. You’d never guess any of that from the way Hollywood has treated Gulliver’s Travels, however. Going back at least to the Fleischer Studio’s cartoon version in 1939, the American movie industry has insisted upon interpreting Swift’s scornful musing on the War of Spanish Succession and the various sectarian bloodbaths of the 17th century as a lighthearted fable for entertaining the kiddies. Some part of Swift’s message might survive the translation to celluloid, but the original tone invariably vanishes without a trace. In that light, it’s remarkable how faithful an abridgement of the book Columbia’s The 3 Worlds of Gulliver is. Intended as the Charles Schneer-Ray Harryhausen team’s follow-up to The 7th Voyage of Sinbad (even the title seems calculated to evoke memories of the earlier film), The 3 Worlds of Gulliver was clearly made with a very young audience in mind, and social criticism as such was understandably not high on its creators’ agenda. But in choosing which elements of Swift’s story to retain, Schneer and screenwriters Arthur Ross and Jack Sher preserved— whether advertently or not— substantially more of its polemical thrust than one would naturally expect.

Lemuel Gulliver (Kerwin Mathews, from Jack the Giant Killer and The Warrior Empress) is a doctor living in the small English village of Wapping. The local economy isn’t exactly booming, and Gulliver’s patients are far more likely to pay for his services with live chickens and IOUs than with hard cash. This is a problem because Gulliver’s fiancee, Elizabeth (June Thorburn), is determined to make a homeowner of him as soon as possible, and nobody (not even in Wapping) is much inclined to accept a herd of chickens as a down-payment on a house. Gulliver does, however, have ten pounds saved up, and Elizabeth has found a fair-sized cottage whose owner is willing to settle for even that small a sum as the opening installment for its purchase. But when Elizabeth takes Gulliver around to see the house, it becomes immediately obvious why the price is so low— the place is a dump, and I for one would be very impressed if it were still standing by the time the couple were ready to move in. A fight breaks out between Gulliver and Elizabeth at this point, and it’s difficult to see either one of them as being entirely in the right. On the one hand, Elizabeth is being ridiculous if she thinks the crumbling cottage will ever be a suitable site for the sort of life she wants to build with her future husband, but on the other, Gulliver seems to be placing far too much emphasis on the need for monetary prosperity in a community that still primarily gets by with a barter economy. And both participants are looking at the issue sideways when they accuse each other of excessive materialism (Elizabeth because Gulliver wants to secure his finances before he settles down with her, and Gulliver because Elizabeth insists upon their diving headlong into the real estate market right this second). The fight escalates until Elizabeth declares their relationship over, and storms out of the blighted house. Gulliver, in turn, takes the local sea captain up on his offer to hire him as the ship’s doctor on the next voyage.

Elizabeth obviously believes that she had been too hasty, however, for she stows away aboard the same ship when it sets sail a day or two later. She is not discovered until the vessel is far out to sea, and the result is another row between the two lovers, this time over whether or not Elizabeth is going to disembark and head back to England at the first port of call. Neither Gulliver nor Elizabeth wants to have this argument in front of the crew, understandably, so they both go above decks to have it out with each other. Unfortunately, there happens to be a tempest raging at the time, and Gulliver is washed overboard when the ship takes a mass of green water across the upper deck. Elizabeth (who’s never been to sea before in her life) has no idea what to do, and the crew are unable to mobilize in time to rescue Gulliver before he is pulled away by the heaving seas.

Gulliver washes up on a beach alive, but somewhat the worse for wear. He won’t know this for a while yet, but he’s on the uncharted island of Lilliput, and two of the natives are conversing urgently not far away from the stretch of sand where the waves deposited him. The man is Reldresal (Jack the Ripper’s Lee Patterson), an official of the local government in line for the post of prime minister, while the woman is his lover, Gwendolyn (Jo Morrow, of 13 Ghosts and Dr. Death: Seeker of Souls). The two Lilliputians have a problem, for Gwendolyn’s family has been banished for their opposition to the emperor (Basil Sydney, from Transatlantic Tunnel and The Hands of Orlac), while Reldresal has remained a loyal member of the imperial cabinet. Gwendolyn’s father wants to leave at once, Reldresal wants a chance to use his soon-to-be-increased authority to prevail upon the emperor to rescind his banishment decree, and Gwendolyn herself wants Reldresal to run away with her, even though her dad refuses to entertain any idea of trafficking with a loyalist. Meanwhile, Reldresal’s main rival for the premiership, another cabinet minister named Flimnap (Martin Benson, from Gorgo and The Strange World of Planet X), is on his way to the shore with a contingent of soldiers, having been tipped off by his spies that Reldresal is consorting with a disgraced rebel. Flimnap attempts to have Reldresal arrested, but before much can come of the ensuing sword fight between him and the gendarmes, Gulliver regains consciousness and gets all the combatants’ attention. This is not hard for him to do, because the Lilliputians turn out to be roughly six inches tall, and there’s nothing like a wakening giant to make people drop whatever else they might have been doing. Gulliver isn’t in a position to do anything just now beyond groaning loudly and rolling over onto his back, however, and Flimnap springs into action at once, summoning more soldiers and the Lilliputian army’s corps of engineers. By the time Gulliver’s faculties are fully restored, the horde of tiny men have bound him to the beach with a skein of ropes and a forest of miniature tent-pegs. Then the emperor arrives. His first instinct is to have Gulliver executed at once (lots of luck, there— the archers’ arrows may all be poisoned, but it seems an open question to me whether their three-inch shortbows could shoot them with sufficient force to penetrate Gulliver’s epidermis, let alone his clothing), but soon he arrives at a better idea. Lilliput, you see, is at war with the inhabitants of a neighboring island called Blephescu, and the emperor figures a giant on his side would tip the balance irrevocably in Lilliput’s favor. Gulliver isn’t so sure he wants to be anybody’s secret weapon, but if it gets him untied and fed, then he’ll happily keep his mouth shut for the time being.

Unanswerable military power isn’t the only thing Gulliver has in common with a hydrogen bomb. He’s an extremely controversial presence on the island, with the empress (Marian Spencer, from Corridors of Blood and The Spell of Amy Nugent) swooning over him (well, what do you know— a size queen…), Flimnap lobbying constantly for his execution on the grounds that his appetite is bankrupting the kingdom, Reldresal seeking his aid in outmaneuvering Flimnap for the premiership, and the commoners of Lilliput rejoicing over the value of his gigantic strength for land-clearing and crop-tilling. Gulliver, for his part, is just happy to have the opportunity to do good for society on such a scale, and he also thinks his sheer intimidation value might be enough to bring the war against Blephescu to an end with little or no bloodshed. He becomes a bit less sanguine about the latter prospect once he finally learns what is at issue in the conflict— the Lilliputians crack open their breakfast eggs at the small end, the Blephescuans crack theirs at the big end, and each side condemns the other’s egg-opening practices as heathen and barbarous. Nor is the emperor willing to countenance Gulliver’s proposed compromise of cracking the egg right in the middle. Just about any war can be made to seem stupid if you consider it from the right angle, but surely this sets some kind of record. Gulliver understandably conceives a desire at this point to get the hell away from all these demented little pixies just as fast as he possibly can.

Even once he succeeds in escaping from Lilliput, Gulliver’s travails are not at an end, for there is another uncharted isle standing between him and Great Britain. Whereas Lilliput and Blephescu were the domains of miniscule war-mongers, Brobdignag is inhabited by arrogant giants. Gulliver discovers this when he attempts to talk to some human-sized dolls belonging to a “little” girl named Glumdaclitch (Sherry Alberoni, of Cyborg 2087 and Barn of the Naked Dead). Glumdaclitch snatches Gulliver up and takes him to the castle of King Brob (Gregoire Aslan, from Le Sex Shop and Blood Relations), who has decreed that all of his subjects are to do so whenever they find one of the diminutive organisms that populate the outside world. He collects such creatures, you see. Glumdaclitch is not happy to learn that she is expected to hand over her find, but the Brobdignagian queen (Mary Ellis) defuses the conflict by suggesting that the girl could take up residence at the castle and become keeper of King Brob’s miniature menagerie. Gulliver is taken to live in a majestic dollhouse, where he discovers that he’s going to have a roommate. Evidently that storm wasn’t the last misfortune to befall his old ship, because moving into the dollhouse means moving in with Elizabeth. This seems like sort of a good deal at first (and it seems like an even better deal once Gulliver convinces King Brob to have him and Elizabeth married), but things turn rather sour when the queen falls ill with a bellyache, and Gulliver proves more successful at treating her than Makovan the court alchemist (Charles Lloyd Pack, of Old Mother Riley Meets the Vampire and Enemy from Space). Makovan concludes that Gulliver must be a witch, and King Brob comes to share that opinion when Gulliver trounces him at chess. Furthermore, the Brobdignagians, unlike the Lilliputians, are in a credible position to act on their displeasure with Gulliver. Specifically, the king means to feed him to his pet crocodile— which, while tiny from Brob’s perspective, is a good 25 feet long from where Gulliver is standing.

Yeah, they’re counting Wapping as one of the three worlds. That kind of irritated me, too. Also irritating is the attitude with which Gulliver attempts to enlighten everybody he meets on his curious voyage, an attitude that was supposed to be saintly, but comes across as smug the way Kerwin Mathews plays it. In my opinion, they ought to have tried for simple naivety instead, which is something that an actor of Mathews’s limited abilities might have managed. At least he doesn’t have to be convincing as a swashbuckling action hero this time around, which puts his performance here a little ways ahead of his turns as the lead in The 7th Voyage of Sinbad and Jack the Giant Killer. A second point in The 3 Worlds of Gulliver’s favor is, expectedly, Ray Harryhausen’s special effects. Truth be told, Harryhausen was rather overqualified for this movie, which offers little scope for his famous stop-motion animation. (King Brob’s crocodile is a Dynamation creature, as is— and this is my favorite bit in the whole movie— the gargantuan squirrel that attacks Gulliver and Elizabeth when they sneak out of the castle for their honeymoon.) Mostly, it’s a matter of forced perspective and matte effects, and while Harryhausen handles those beautifully, they’re nothing that Bert I. Gordon couldn’t have pulled off if he’d had some money to spend. A slumming Ray Harryhausen is still Ray Harryhausen, though. But the biggest treat, as I’ve hinted already, comes in the screenplay, which includes a few bits of authentic Swift that simply cannot be shorn of all their satiric power, no matter how hard their adaptors may try. The 3 Worlds of Gulliver may be a juvenile fantasy, but so long as people are fighting a war over the correct way to open an egg, some hint of Swift’s contemptuous anti-militarism is going to shine through. Ross and Sher also retain a surprising amount of the novel’s bawdiness, although they’ve done so in a way that seems aimed over the main audience’s heads. The scene in which Gulliver puts out the fire at the Lilliputian imperial palace has been bowdlerized (you can’t hide a piss joke from a seven-year-old— it’s just not possible), but the less sophisticated children of 1960 very likely wouldn’t have fully caught on to what Gulliver and Elizabeth are impliedly up to under the cover of their humongous marriage license during and immediately after the wedding ceremony. Still, the good points of The 3 Worlds of Gulliver seem to resist coming together right, while the bad points all too often achieve a powerful negative synergy. The combination of kid-centric handling and residual message-mongering amounts, as it so often did in the 60’s, to patronizing and condescension, especially during the groan-inducing final scene. (Those public service announcements they used to run at the end of the episode on “G.I. Joe” were more subtle.) Kerwin Mathews is just not leading-man material, and he has no chemistry at all with June Thorburn except when the two of them are both completely hidden from sight by 100 square feet of notarized parchment. And even some of the special effects set-pieces are undone by budgetary considerations, as when the “invincible armada” that Gulliver has to face down off the coast of Blephescu turns out to consist of four lousy sloops of war. Schneer and company plainly tried with this one, but they didn’t try quite hard enough.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact