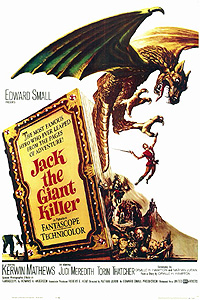

Jack the Giant Killer (1961/1962) **Ĺ

Jack the Giant Killer (1961/1962) **Ĺ

Howís this for screwing yourself over? When producer Charles Schneer and special effects maestro Ray Harryhausen were just getting started on the project that would become The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, one of the first people they spoke to about funding was another producer named Edward Small, who was affiliated with the United Artists distribution network. Small evidently saw nothing to be gained from backing what promised to be a relatively expensive production, probably reckoning that monster movies in the 1950ís needed to be on a sci-fi footing in order to succeed at the box office. Well as it happened, Schneer and Harryhausen were merely ahead of the curve. The ďriskyĒ movie that Small turned down ended up making an astonishing $12 million for Columbia (the studio that ultimately released it), and the ensuing succession of similar Schneer-Harryhausen fantasy films were, for the most part, respectable successes in their own right. You can imagine how steamed Small must have been. Eventually, he came to the conclusion that he really did need a piece of that action for himself, and by 1961, Jack the Giant Killer was ready for the theater. Smallís movie was an unusually detailed copy of its inspiration, too. It had Nathan Juran, the director of The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, calling the shots on both Kerwin Matthews and Torin Thatcher (who had played the earlier filmís hero and villain, respectively), and its plot structure (if not necessarily the details of the story) was so similar to that of the Schneer-Harryhausen movie that Columbia actually sued for copyright infringement, holding up the release of Jack the Giant Killer until the year after its completion. What Jack the Giant Killer did not haveó and this probably goes the farthest toward explaining why it commands less recognition today than even the most obscure of Columbiaís movies in the same veinó was Ray Harryhausen. The biggest star on its effects team was Jim Danforth, and his most significant work was so far in the future in 1961 that he didnít even get his name in the credits here. As for the rest of the bunch, letís just say that a couple of guys who used to sculpt facial appliances for Universal during the mid-1940ís were no substitute for the most talented apprentice of stop-motion animationís original grandmaster. Edward Smallís bid to correct the mistake he had made in passing on the Sinbad film is the very essence of ďa day late and a dollar short.Ē

But for all that, Jack the Giant Killer still manages to be a respectably entertaining fantasy adventure flick. A voiceover intro explains that Cornwall was once held in thrall to Pendragon (Thatcher, also in The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll & Mr. Hyde), the Prince of Witches, but that a powerful wizard eventually rose up to defeat Pendragon and banish him, together with his army of giants, witches, and hobgoblins, to a remote island in what I assume to be the North Sea. However, Pendragon (apparently in contrast to the wizard who bested him) is immortal, and thus has literally all the time in the world to plot his triumphant return to the mainland. As the story proper begins, Cornwall is ruled by the just and much-loved King Mark (Dayton Lummis, who had small parts in The Bad Seed and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea), who is receiving visitors from all over his realm to celebrate the birthday of his daughter, the Princess Elaine (Judi Meredith, from Queen of Blood and The Night Walker). Unbeknownst to Mark, one of those visiting lords, the ostensible Count of Tartan, is really Pendragon in disguise, and the gift he offers the princess is really the centerpiece of an ingenious abduction scheme. What looks at first glance to be a music box opens up when activated to release a dancing automaton in jesterís motley; this clockwork homunculus is in truth the giant Cormoran, shrunk by his masterís magic so as to infiltrate the castle. After Elaine goes to bed, Pendragon releases the spell, and Cormoran grows to his full size, seizing the princess and smashing his way out through the castleís main gate. Mark and his soldiers go in pursuit, naturally, but Cormoran has a long stride, and the chase is pretty well hopeless.

But just moments before Cormoran was to rendezvous with Garna (Walter Burke, from the 1951 version of M and Edward Cahnís Beauty and the Beast), Pendragonís most trusted servant, the giant tramps through the farm where a young man named Jack (Kerwin Matthews, of Nightmare in Blood and The 3 Worlds of Gulliver) makes his home, and the situation turns sharply against the evil sorcerer. Jack is the son of a royal archer, and Elaineís plight awakens the hero within him. The battle is close-fought, but some inventive use of the rigging inside the farmís flour mill keeps Cormoran immobilized long enough for Jack to open up the giantís jugular with a scythe. The king and his men arrive on the scene just as the monster breathes his last, and Jack suddenly grasps what a big deal his already impressive deed really is. King Mark knights Jack almost immediately, and entrusts him to serve as his daughterís personal bodyguard.

The royal chancellor (Tudor Owen, of The Black Castle and The Most Dangerous Man Alive) believes he recognizes the immense carcass in Jackís field, and some digging in the archives brings to light a scroll from Markís grandfatherís time, which tells all about Pendragon and his monstrous minions. That convinces the king that Elaine remains in grave danger, and he conspires to have Jack spirit her away to safety in a French convent. Pendragon has agents even within the royal household, however, for Constance, Elaineís lady-in-waiting (Anna Lee, from Bedlam and Picture Mommy Dead), is under a spell bending her to the witch-princeís will. Constance dispatches her pet crow with a message to Pendragon, explaining exactly what Mark intends to do to protect his daughter. Thus when Jack and Elaine, disguised as peasants, are within sight of the French coast, a contingent of Pendragonís witches swoop down upon the ship and hold Jack and the crew at bay until they have the princess securely in their clutches. The vesselís captain (Robert Gist) dies in the fighting. Jack wants to chase after the retreating witches, but the surviving members of the crew will have none of that. They force Jack overboard, and when a drunken Viking fisherman named Sigurd (Barry Kelley) pulls him from the Channel, his only remaining ally from the ship is Peter (Roger Mobley), the captainís young son, who jumped in the drink after Jack rather than consent to sail with a gang of mutineers.

You may be wondering by this point just what Pendragonís game is. Well, as Pendragon himself explains when he drops in on King Mark shortly after capturing Elaine, he means to blackmail the king into abdicating his throne. Elaine, as Markís only child, would then ascend to his place, and the evil wizard, as chancellor or perhaps even prince-consort, would become the de facto ruler of Cornwalló from which position his forces would be easily able to overrun all of England. Pendragon gives Mark a week to consider his demands, after which something very unpleasant will most likely befall Elaine. Naturally, the immediate practical result of this is that Jack has a quest to undertake.

In point of fact, something very unpleasant has already befallen Elaine, for Pendragon has bewitched her in the same way as he bewitched Lady Constance. Consequently, when Jack, Peter, and Sigurd make their way to Pendragonís island stronghold, Elaine can in no way be trusted to cooperate with her rescue, and can probably be counted as an even bigger threat than the witches, giants, and clockwork soldiers that constitute Jackís more overt opposition. Luckily, Jack has some magic of his own, for one of the more interesting bits of flotsam that Sigurd has drawn from the sea over the course of his career is the enchanted bottle in which a leprechaun (Don Beddoe, from Before I Hang and Night of the Hunter) was imprisoned a thousand years ago for dabbling in the black arts. In exchange for his freedom, the leprechaun agrees to do Jack three favors during the contest against Pendragon and his minions.

SoÖ Evil sorcerer? Check. Captive princess? Check. Tiny creature of enormous magical power locked up inside some readily portable vessel? Check. Climactic battle involving a stop-motion dragon? Check. Hell, even the design for the model giants is cribbed from The 7th Voyage of Sinbadó the only difference between Cormoran and Harryhausenís cyclops (apart, I mean, from Cormoran kind of sucking) is that Cormoran has two eyes! I can see why Columbiaís lawyers would call shenanigans as soon as they had a look at Jack the Giant Killer. Itís very strange, then, that this movie should feel so much fresher and so much more free-spirited than its obvious model when youíre actually watching it. Jack the Giant Killer is aimed much more directly at a juvenile audience than The 7th Voyage of Sinbad seems to have been, and it benefits from a childlike willingness to just pull stuff out of its hat without worrying much about how tightly it fits with what weíve seen already. Consider: a folk hero from Cornwall gets attacked at sea by flying witches and forced overboard; he gets rescued by a Viking; the Viking has a leprechaun in a bottle for a pet. It feels like Nathan Juran (who, in addition to directing, co-wrote the screenplay with Orville H. Hampton) is just making this shit up as he goes along, but in a good wayó the way a talented storyteller improvises when he suspects his audienceís interest is starting to flag. It is the resulting bedtime-story feeling, I think, that accounts for my paradoxical impression that Jack the Giant Killer is a more successful film, on its own terms, than the more entertaining and in most respects better-made The 7th Voyage of Sinbad. The earlier movie had ambitions which it hadnít a chance in hell of realizing, weighed down as it was by all the outrageous overacting and atrocious fake accents; Harryhausenís creatures were awesome, but the surrounding film really was not worthy of them. Jack the Giant Killerís sights are set lower, and as a consequence, it comes closer to achieving its aims. It is also significant that in Jack the Giant Killer, the humans mostly come across better than the monsters.

Letís talk a bit about those monsters now, shall we? As I said, the giant Cormoran, who dominates the movieís first act, is a completely shameless copy of Harryhausenís cyclops, albeit created and animated with none of Harryhausenís skill. Cormoran is nevertheless about the most effective of Jack the Giant Killerís stop-motion creatures. The second giant who shows up shortly before the grand finale (he doesnít get a name so far as I noticed, but since the folkloric Cormoran had a brother called Blunderbone, thatís how I think of him) is a sad creation indeed, despite the appealing touch of his having two heads, but even he looks good beside the almost indescribable (and almost indescribably cheesy) sea monster summoned by the leprechaunís magic to fight him off. The dragon into which Pendragon eventually transforms himself is odd to say the least. A certain amount of additional care was expended on it, as befits its role in the climactic battle, and some portions of the dragonís midair grapple with Jack work very well; at other times, the dragon looks like something Ben Cooper Toys might have sold to Dart Drug around Halloween. Curiously enough, my favorite members of Jack the Giant Killerís monstrous menagerie are not animated at all, however. Though the script calls them ďwitches,Ē the creatures Pendragon unleashes upon the ship transporting Elaine across the English Channel are nothing so simple as a bunch of warty women wearing pointed hats. Their leader is a sort of three-horned gargoyle wielding a trident that shoots fire from its tines; the witch who administers the sleeping potion to the princess is zombie-like, with most of the skin rotted off of her face; strangest of all might be the one who does most of the work of fending off Jack and the sailorsó beneath her tangled mane of white hair, she has the flattened, elongated head of a snake, and a funnel of wind blasts constantly from her gaping mouth. And all of them emit weird auras of pulsating blue light. Itís incredibly freaky, and the succession of images it creates is so striking that it jolted me into remembering that I had seen Jack the Giant Killer before, at my paternal grandparentsí house when I was very young. Any movie that can dig itself a little burrow like that in the back of my brain (assuming it does so by impressing me, of course) gets a few bonus points from me, no matter how shabby it might be in sum.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact