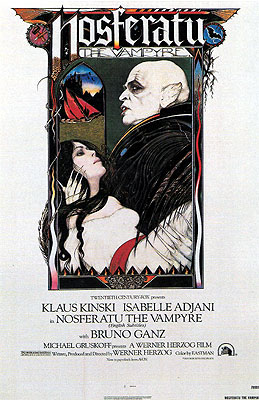

Nosferatu the Vampyre / Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979) *****

Nosferatu the Vampyre / Nosferatu: Phantom der Nacht (1979) *****

Director Werner Herzog once said that it was among his life-long ambitions to make a movie as good as F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, which he called “the most important movie ever made in Germany.” Whether he realizes it or not, since 1979, Herzog’s list of life-long ambitions has been shorter by one entry. So far as I’m concerned, his remake of the classic film, Nosferatu the Vampyre, is nothing less than the greatest traditional vampire movie of all time. It may seem strange to lavish such praise on a mere remake, but in this case the hyperbole is fully merited. This film is a sterling example of how a remake ought to be done. Herzog is faithful to the tone and subject matter of the original (amazingly enough even reusing some of the same locations-- including the creepy old ruined mansion in Wismar!), but he takes the story in fresh directions, downplaying some of the ideas dealt with in his model while expanding upon others which the previous version only touched on in passing, and incorporating entirely new themes of his own invention. His work here reflects an intimate understanding of his source material-- a profound sense of both its strengths and its weaknesses, and a firm grasp of how those strengths and weaknesses operate. And most importantly, Herzog succeeds brilliantly in translating that understanding into a compelling film.

Herzog’s script generally follows the contours of the original Nosferatu’s. Jonathan Harker (Bruno Ganz, of The Boys from Brazil), a real estate agent from the idyllic seaside town of Wismar, is informed by his boss, Renfield (Roland Topor), that a new assignment has come in, for which only he is suitable. The Transylvanian nobleman Count Dracula (Klaus Kinski, from Deadly Sanctuary and Crawlspace) wishes to buy a house in Wismar, and Renfield believes the abandoned mansion across the street from Harker’s place is just what he is looking for. The count is very rich, and Harker stands to make an enormous amount of money from the sale, money which he desperately desires for the sake of buying a new home for himself and his young wife, Lucy (Possession’s Isabelle Adjani, who more recently appeared in the crass American remake of Diabolique). The only snag is that Transylvania is some four weeks’ journey away by road, and Count Dracula, though a free spender, is not a patient man. Thus if Harker wants the job, he will have to leave immediately. Neither Harker nor his wife is terribly pleased about that last part, and Lucy is also haunted by premonitions that grave peril awaits her husband in Transylvania, but both understand that this assignment means the difference between realizing their domestic dreams in the immediate future and putting them off for a later day that may never arrive. After a short trip to the beach for a lingering goodbye, Jonathan leaves Lucy in the care of her friend Mina (Martje Grohmann) and sets off on the long road to the Carpathians.

Four weeks later, Harker arrives in a tiny Transylvanian mountain village, where he stays the night at an inn. These villagers are just as alarmed to hear that Harker is bound for Castle Dracula as those in Murnau’s version were, and they actively stand in the way of the last leg of his journey. The chambermaid at the inn (Margiet van Hartingsveld) puts an old book on the subject of vampires on the bedside table in his room. A coachman (John Leddy) turns him away, saying, “Can’t you see-- I have no horses,” while he grooms an entire team of them right before Harker’s astonished eyes. The innkeeper goes so far as to introduce Harker to a company of Gypsies who have been to Dracula’s neighborhood, so that he might hear of its dangers from eyewitnesses. What they have to say is troubling indeed. According to the Gypsies, there is no Castle Dracula, only the haunted ruin of a medieval fortress which appears to be inhabited in the hours of darkness, when the evil spirits who dwell there may exercise their Satanic power. But Harker believes the Gypsies no more than he believes the innkeeper; after all, he has a signed letter from Count Dracula calling for his professional services, and evil spirits neither write letters nor invest in real estate.

Ah, but perhaps they do on occasion. After many hours trudging through the mountains, Harker at last spies Castle Dracula perched on one of the upcoming peaks. The place certainly looks like a ruin to me, and it’s difficult to imagine anyone but a vengeful ghost living in such a place. But when Harker arrives at its main gate, the brooding fortress seems a bit weather-beaten, but basically intact. Depending on your mood, you could take that as either reassuring or ominous, but there’s just no choice regarding Harker’s first impression of his host. Count Dracula is the creepiest son of a bitch in Europe. Herzog’s makeup man followed Murnau’s very closely when it came to the count’s appearance, and Klaus Kinski makes a passable stand-in for Max Schreck. Kinski also mimics Schreck’s outlandish mannerisms, which become, if anything, even more distressing in his hands. Much of the movie’s running time is spent here in the castle, in which Harker realizes too late that he has become a prisoner. Herzog does a better job with this than Murnau, whose Hutter/Harker comes to look impossibly dense before he finally stumbles upon Count Orlock’s coffin, stubbornly failing to grasp one clue after another as to his host’s nature. Herzog’s Harker only needs to be attacked once; rather than dismiss the experience as a horrible nightmare, he goes on a deliberate search for the coffin, which his nightly readings in the chambermaid’s book have convinced him must surely be on the premises. But the discovery does him little good, because he has not yet reached the chapter that explains what a person must do with a vampire once it has been found out, and he is prevented from fleeing home to Wismar by his “host’s” sensible precaution of locking all the doors and gates leading out of the castle. Harker is forced to escape through the window of his room, the final impetus goading him to action coming when he sees the vampire making his arrangements to leave for Wismar.

The trouble is that Harker’s room is not on the ground floor, and he knocks himself senseless on the cobblestones of the courtyard below. He remains unconscious for the rest of the night, and when he awakens sometime after dawn, he isn’t feeling at all well. Part of his problem stems, I’m sure, from the lingering effects of his fall, and some of it must also be due to weakness from loss of blood. But considering how much better he seemed to be doing the previous night, it seems to me that the main source of Harker’s discomfort comes from the effects of the sun on his partly-vampirized physiology. But sick or not, Harker knows he has no time to spare, and that the race is on between him and Count Dracula to see which of them can reach Wismar-- and Lucy-- before the other. Harker goes by land-- all things considered, he hasn’t much choice in the matter. Count Dracula, on the other hand, travels by barge to the Black Sea port of Varna, where he is packed aboard a ship on the fiction that his coffins contain “garden soil for botanical experiments.” The certainly do each contain an awful lot of soil, but as we shall soon see, their principal cargo is a horde of rats. 400,000 of them, in fact. And all of them carrying the plague.

Back in Wismar, the past couple months have been difficult ones for Lucy. Her premonition that danger waited for Harker has crystallized into a morbid certainty that some ghastly fate has already befallen him. (Not a bad call, at that...) She’s also been having strange dreams, begun walking in her sleep, and suffered from seizure-like episodes in which she falls down on the floor and begins screaming about something terrible happening to Jonathan and something even worse coming to Wismar. The ship carrying Count Dracula and his rats arrives on the very day that Lucy decides she’s had enough, and goes to see Renfield in the mental hospital to which he was recently confined-- she hopes to get directions to Dracula’s place from the madman so that she can go looking for Jonathan herself. As it happens, that isn’t necessary, for Harker makes his way back home that day, or perhaps the next. He’s still very sick, and despite the attentions of Dr. Van Helsing, the town physician (Walter Ladengast, from the 1961 German remake of The Dead Eyes of London), he seems only to be getting worse.

And that’s when the citizens of Wismar begin dropping like flies of the plague, which has already decimated Varna, the vampire’s port of embarkation. Dracula’s rats have completely overrun the city within days of his arrival, and it soon looks as though the whole town will be wiped out if something is not done about them. Meanwhile, a couple of stiffs turn up whose demise cannot be linked to the plague, though Van Helsing has no idea what else could have caused it-- who, after all, ever heard of anyone dying from a pair of tiny cuts on the throat? Lucy, however, thinks she knows what’s what. She’s been reading her husband’s diary from his stay at Castle Dracula, and she thus knows everything that went on there. When a lust-struck Dracula pays Lucy a personal visit in her bedroom soon thereafter, sneaking up behind her while she combs her hair before a mirror fully large enough to reflect the entire room (I can’t even describe how cool this looks onscreen), she gets all the confirmation she needs. It’s a good thing for her she wears a gold cross on a chain around her neck...

But even with proof of this sort at her disposal, Lucy cannot convince Dr. Van Helsing that a vampire is on the loose in Wismar. Fortunately, though, his diary was not the only book Harker brought back with him from Transylvania. Lucy also reads the book the chambermaid gave Jonathan, and thus is able to determine how to get rid of Count Dracula. The prescription is the same as it was in Murnau’s Nosferatu: a woman pure of heart must seduce the undead monster and induce him to linger by her side until the sun rises to destroy him. And as with Murnau’s Nosferatu, Lucy takes it upon herself to make the almost certain sacrifice in order to save the lives of those few who remain in Wismar. As downbeat as the note on which Murnau ended his version of this story was, Herzog’s conclusion to the tale is even bleaker.

It isn’t very often that a horror movie rises to the level of high art (hell, thousands of them can’t even make it to low art!), but with Nosferatu the Vampyre, Werner Herzog has pulled off precisely that. The movie is absolutely beautiful to behold, displaying Herzog’s remarkable mastery of his medium with every frame. The director’s use of light and shadow is fully up to the very high standard set by Murnau, and Herzog proves equally up to the considerable challenge of replicating the earlier film’s grim, moody atmosphere on color film. He succeeds even despite the phenomenal scenic beauty of most of his locations; this is most obvious in those scenes set by day in Dracula’s castle. Even with the sun shining in and reflecting off the spotless white walls, the castle is an eerie, threatening place. Herzog is just as successful in cloaking the ship on which Dracula travels with an aura of menace, without resorting to Murnau’s trick of rigging its masts with black sails.

But unlike many visually stunning films, Nosferatu the Vampyre is not just empty eye-candy. Its story is gripping, despite its dirge-like pace, and its characters are well-drawn and adeptly portrayed by the cast. Kinski is obviously the big attraction, and though he is perhaps less frightening in the part than Max Schreck had been, he also plays the vampire with more depth and nuance, but without veering into the territory of maudlin self-pity that has characterized so many cinematic vampires in the post-Anne Rice era. Furthermore, Kinski is aided by Herzog’s reworking of the storyline to make the danger posed by Count Dracula loom far larger than it had in Murnau’s version. Herzog’s Dracula is only secondarily a vampire; first and foremost, he is the incarnation of the Black Death. Murnau had toyed with this idea back in 1922, and had drawn a strong connection between Count Orlock and the plague, but Herzog takes it much farther, raising the threat posed by the vampire-directed pestilence to truly apocalyptic proportions. At times the film even comes to resemble and to echo the morbid power of the nightmarish, plague-inspired paintings of the late 14th century.

But as impressive as Kinski and his character are, they do not overshadow Bruno Ganz’s Harker or Isabelle Adjani’s Lucy. Unlike Gustav von Wangenheim’s take on the same character, Ganz is fully believable in his role. His Harker is an ambitious, hard-working man who is shown early on to be willing to undertake the greatest of hardships for the sake of his beloved Lucy; the journey to Transylvania is certainly the greatest sacrifice that he has yet been asked to make, but one gets the feeling that he sees the difference as a matter of degree only. Ganz’s air of solid practicality makes the undertaking far more credible coming from him than from the rather foppish von Wangenheim. And with Adjani playing Lucy, it is not hard to see why a man would be willing to sacrifice much on the character’s behalf. Her radiant beauty is almost beside the point; the sensitivity, loyalty, and vulnerability (but never weakness or helplessness) that she conveys would be more than enough all by itself.

As with Murnau’s film, there is more than one version of Nosferatu the Vampyre available. The noticeably inferior English-language version is the more common in the U.S., but a German dialogue/English subtitles version also turns up from time to time. The relationship between the two variants is curious indeed. Contrary to what you might expect, the English version is not a dub. Rather, it was a sister production to the German-language version; Herzog would shoot a scene in German, and then shoot it again with the actors delivering their lines in English. This must have led to thousands of tiny differences between the two, but I have not yet had the patience to attempt a detailed comparison. I have, however, noticed that the performances in the German-language version are significantly better than those in its English-language counterpart. This is especially so in the case of Roland Topor’s Renfield-- Topor apparently spoke English rather poorly, and he is visibly uncomfortable acting in the foreign tongue. I therefore recommend the German version, though the subtitles don’t always stay onscreen long enough, and sometimes omit important details of the dialogue from their translations.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact