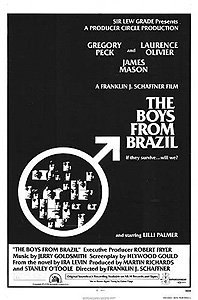

The Boys from Brazil (1978) ***½

The Boys from Brazil (1978) ***½

The world is full of deposed dictators and dictator hangers-on, whiling away their imposed retirement living high on the hog on money looted from the treasuries of the countries from which they were forced to flee— perhaps you remember the recent international extradition battle over Pinochet? Hell, there are some places in the Third World these days where it seems you can scarcely turn around without bumping into two or three former African or Central American strongmen. But in the West at least, none of these people have so strongly captured the cultural imagination as the ex-Nazis. Nevermind that most of the really important ones either died during the final days of the war, or were snapped up in time to stand trial at Nuremberg— ever since the Israeli secret service kidnapped Adolf Eichmann and shipped him off to face the courts in Jerusalem in the early 1960’s, writers and filmmakers working in the more paranoid genres (and few can be as paranoid as horror and science fiction) have periodically raised the specter of un-punished war criminals hiding out in Brazil or Argentina or some such place, lying in wait with nefarious schemes for bringing about the Fourth Reich. And like I said, it’s only the Nazis that get this kind of treatment; you’ll never see a movie about mad scientists concocting pernicious plans and devilish devices meant to secure world domination for Idi Amin. (Although now that I’ve said that, just you watch— some crazyman with a camera is going to do precisely that. Nature’s abhorrence of vacuums is just as strong a force in the world of exploitation movies as it is in physics.) There would seem to be two probable explanations for this phenomenon. One, most Westerners couldn’t even find Uganda on a map, but we all have at least a passing familiarity with Germany. Two, Hitler and his followers combined seemingly impossible levels of personal villainy with global-scale ambition and enough military and economic power to make the rest of the world take that ambition seriously. The only other figure who comes even close to representing the same combination of malevolence, ambition, and power is Joseph Stalin, but he made it an avowed policy to kill off anyone in his employ who was as bad as him, thereby denying the world its chance to harbor paranoid fantasies about Genrikh Yagoda hiding out in Indonesia, taking orders from the General Secretary’s pickled brain. Naturally, most of the books and movies on the subject of scheming ex-Nazis have been really trashy and really stupid— I refer you to the archetypal They Saved Hitler’s Brain— but there is at least one that is well enough thought-out for an intelligent person to take it halfway seriously: Ira Levin’s The Boys from Brazil and the movie made from it by Franklin Schaffner and Heywood Gould.

Our story begins with a young Jewish man by the name of Barry Kohler (Steve Gutenberg— yes, that one) sneakily following a well-dressed old man around some city in Paraguay. The old man is an escaped Nazi war criminal of minor importance, and Barry, a self-styled Nazi-hunter, has been trailing him ever since he noticed how many other second- and third-string ex-Nazis he’d been meeting with lately. And over the course of today’s investigative outing, Kohler turns up evidence that he may be on to something big; his quarry spends the afternoon picking up a first-string ex-Nazi, a former commandant of Dachau, at the airport.

Intoxicated with excitement at what he has learned, Barry calls his hero, professional Nazi-hunter Ezra Lieberman (Laurence Olivier, from Clash of the Titans and the 1979 version of Dracula), at his home/office in Vienna. Lieberman is less than impressed. As he snidely tells his sister, Esther (Lilli Palmer, of Night Child and the 1971 version of Murders in the Rue Morgue), “This young man has just discovered that there are Nazis in Paraguay.” His advice to Kohler: “Get on a plane and go home. Better yet, go to the American embassy and have them put you on a plane. Yes, there are Nazis in Paraguay, and if you stay there, there will still be Nazis in Paraguay, but there will be one less Jewish boy in the world.” But Barry knows he’s uncovered something significant, so he presses on without Lieberman’s help, bribing a pre-teen boy who works in the old Nazi’s mansion to plant a homemade bug in the mansion’s parlor. No sooner has he done this than the old man has a big gathering of ex- and neo-Nazis over at his place. The guest of honor: no less a personage than Josef Mengele, Auschwitz’s legendary Angel of Death (Gregory Peck, from The Omen and Marooned).

While Kohler listens in, Mengele explains the reason for the gathering. The Comrades’ Organization, a sort of international brotherhood of old Nazis, wants six men to perform a series of assassinations in Europe, Canada, and the United States over a period of two and a half years. The 94 victims, all of them 65-year-old civil servants with positions of minor bureaucratic authority, must each be killed on or about certain specific dates. The assembled executioners are more than a little puzzled by all of this. In the words of one, whose target is the postmaster of an obscure village near Upsala, Sweden, “By killing this old mailman, I will be fulfilling the destiny of the Aryan race?” But Mengele isn’t here to offer explanations, just orders, and both the men carrying out those orders and the eavesdropping Barry Kohler are to be kept in the dark as to the purpose behind them. Then, just as the doctor is about to begin discussing the logistics of the mission in detail, a freak accident with the transistor radio Barry gave the servant boy in exchange for his cooperation leads to the Nazis’ discovery of Kohler’s bug. The young Nazi-hunter high-tails it back to his hotel, where he immediately places another call to Ezra Lieberman. Unfortunately for Barry, Mengele has not only found the bug, but also the identity of its planter, and he is able to extract from the boy both Kohler’s name and the address of the hotel out of which he has been operating. Mengele and his goon squad interrupt Barry’s call to Lieberman with a kick to the door and a knife to the gut. Just days later, the first round of scheduled assassinations begins.

That interrupted phone call has changed Lieberman’s mind about the seriousness of Barry Kohler’s discovery, though, and he quickly calls in some favors. He arranges to have an old journalist friend of his send him wire service clippings about any 65-year-old civil servants dying accidentally or by violence, and begins checking into them, hoping to stumble upon some of the victims of Mengele’s plot. He does, but none of the dead men’s wives can offer him any information that might explain why the Comrades’ Organization would want their husbands killed. Lieberman does notice something awfully peculiar, though. Not only was each of the victims married to a woman much younger than him, two of the women he interviews (one in Germany, and the other in the United States) have teenage sons who are the spitting image of each other. Both boys are extremely pale, with lanky, black hair and piercing blue eyes, and both boys are representatives of the same species of arrogant prick. What’s more, when Barry’s brother, David Benet (John Rubinstein, from Something Evil and The Car), makes such a pest of himself to Lieberman that the old man agrees to take him on as an assistant just to shut him up, a third woman whom Lieberman sends David to interview in London turns out to have a son just like the other two boys.

As you might imagine, all three kids prove to be adopted— illegally— and when Lieberman does some more digging, he discovers that the baby broker who placed the American boy with his family was Frieda Maloney (The Other’s Uta Hagen), an ex-concentration camp guard whom Lieberman just recently got locked up and indicted for her wartime atrocities! More string-pulling gets Lieberman an interview with Maloney in her holding cell, at which point he learns that the Comrades’ Organization has been brokering scores of illegal adoptions, placing infants from Brazil with couples all over Europe and North America. And interestingly enough, each one of those couples has consisted of a low-to-mid-level government pencil pusher and a woman some twenty years his junior.

Meanwhile, Mengele’s overseers in the Comrades’ Organization are becoming increasingly alarmed about Lieberman’s activities. The doctor’s main contact, Colonel Eduard Seibert (James Mason, from Salem’s Lot and Journey to the Center of the Earth), has been using what influence he has in support of the work, but the high command seems to be coming ever more strongly around to the position that Mengele’s project should be terminated or at least postponed. The Angel of Death is outraged when he hears this news. His work is the greatest hope yet for the revival of Nazism, and its nature is sufficiently delicate that its timetable will permit no tinkering. Lieberman’s meeting with Frieda Maloney proves the decisive factor. The old Jew has gotten too close to the truth, and to proceed with the project would jeopardize the whole of the Comrades’ Organization. Over Mengele’s vehement protest, his work is ordered stopped, and his lab in Brazil destroyed.

So what, exactly, has old Josef been up to? You guessed it, he’s making clones. And not just any clones, either— these are clones of Hitler himself! That’s why each of the boys was placed with the kind of families they were, and that’s why Mengele’s assassins have been running around killing the boys’ adopted fathers. Hitler, for those of you who are not up on these things, was the child of a politically conservative civil servant with an extremely authoritarian style of parenting, and a doting mother more than twenty years younger than his dad. When Hitler was 14, his father died, leaving him in the sole care of his indulgent, smothering female parent. Mengele, an accomplished scientist after his own gruesome fashion, is fully aware that identical genes are not enough to make a clone grow up into an exact duplicate of the original organism. It is necessary that the clone be molded by the same kind of environment as well. Thus he has been at pains to reproduce the original Hitler’s upbringing to the maximum extent possible in the second half of the 20th century. And now all that hard work is being thrown away because of Lieberman’s meddling. Well, Mengele won’t stand for it, ya hear?! Orders be damned, he’s going to pay a visit to the next family on the list, and off dad himself. The only problem is, Lieberman is on his way to see the Wheelock family, too. And just for fun, Mr. Wheelock happens to own about three dozen huge Doberman Pinschers, all of them trained to kill in defense of their master. This is going to be interesting.

The Boys from Brazil has two things going for it that raise it above the level at which the Nazis-in-hiding movie generally operates: some fantastic acting from seasoned pros on the one hand, and an unexpectedly well-laid scientific grounding on the other. (Those of you who care about such things might want to add a third feature— the conspicuously enormous budget, with its attendant high-gloss production values.) Gregory Peck is especially compelling in his radically-against-type turn as Josef Mengele. It’s a role a lot of big-name actors probably wouldn’t touch with the proverbial ten-foot pole, but Peck plays it for all it’s worth. The soft-spoken James Mason makes an excellent foil for the blustering Peck as Colonel Seibert, and Olivier’s Lieberman is more or less exactly what is called for in a character whose successes stem as much from sheer, dumb luck as they do from skill and perseverance (though his Old Jew shtick is perhaps a bit heavy-handed). As for the science, it’s all but impeccable in the context of the late 1970’s, and if nothing else, The Boys from Brazil is just about the only movie I can think of that makes a serious effort to address the messier environmental aspects of the problem of cloning. With most movie clones emerging from their Petri dishes as full-grown adults, complete with all the knowledge and personality traits of the person to be copied, a film in which the entire plot hinges on the necessity of reproducing the environment in which the original person was raised is more than welcome. Better still that the movie should also be well made and a lot of fun.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact