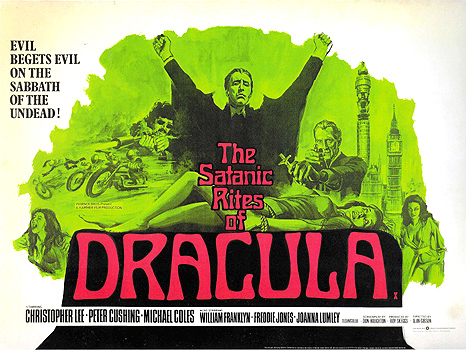

The Satanic Rites of Dracula / Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride / Dracula and His Brides (1973/1978) **

The Satanic Rites of Dracula / Count Dracula and His Vampire Bride / Dracula and His Brides (1973/1978) **

Dracula, A.D. 1972 was the work of a studio whose leaders mistakenly believed that they knew what the ticket-buying public would want going forward. The Satanic Rites of Dracula, the next film in the series, was the work of people who correctly realized that they hadn’t the first fucking clue. 1973 found Hammer Film Productions in a sorry state indeed, operating with little more than a skeleton crew on the office side, while studio boss James Carreras dreamed up slates of ever more fantastical projects that could never be made with the company’s own dwindling resources. Those were the days of Mistress of the Seas, When the Earth Cracked Open, and Zeppelin vs. Pterodactyls, concepts so ill-defined that Hammer actually promoted the second one to potential investors as both a futuristic disaster movie and a prehistoric adventure film. Meanwhile, what was actually turning a profit for the firm were dire sitcom tie-ins like On the Buses and Man About the House, a genre which Carreras could nevertheless not bring himself to embrace fully. The old man wanted Hammer to be Hammer, bless him, even if there was no money in that anymore. Not so surprising, then, that the studio would keep clinging to Dracula’s cape, long after anyone could think of anything worthwhile for the king of the undead to do. Sometimes that kind of desperation yields interesting results, as even the wildest lunacy is granted a chance to make good— and that’s almost what happened with The Satanic Rites of Dracula. This penultimate Hammer Dracula picture keeps the contemporary setting of the preceding installment, and adopts a tighter narrative continuity with its immediate predecessor than ever before, but then erects on that sensible foundation a bizarre edifice of Eurospy, conspiracy thriller, and occult horror elements, reinventing the master vampire as, in Christopher Lee’s own words, “a mixture of Howard Hughes and Doctor No.”

Pelham House is a grand mansion in Croxton Heath, very much like the estates from which Hammer’s two successive studio complexes were converted, and it too is no longer in use as a private residence. Officially, Pelham House has become the headquarters of the Psychical Examination and Research Group, a parapsychology think tank of the sort that briefly became halfway respectable in the 1970’s. Unofficially, however, it’s the headquarters of something much more sinister, and an agency of the British government under the leadership of one Colonel Mathews (Richard Vernon, from The Tomb of Ligeia and Village of the Damned) has undertaken to discover exactly what. A subordinate of Mathews by the name of Hanson (Maurice O’Connell, of The Medusa Touch) infiltrated the group as a security guard (curiously, the PERG security staff are all bikers who dress vaguely like Vikings), but was found out before he could slip away to deliver his report. Hanson held his tongue throughout a harrowing ordeal of torture, and even managed to escape captivity, but he dies after a hasty and understandably somewhat incoherent debriefing. The most immediately important thing, though, is that Hanson claims to have seen John Porter (Richard Mathews), the cabinet minister to whom Mathews directly reports, at Pelham House, taking part in some truly sordid shit. The colonel and his right-hand man, Torrance (William Franklyn, of Enemy from Space and The Snorkel), will therefore have to tread very carefully going forward— and Mathews himself should stay out of the hands-on investigation altogether for the sake of plausible deniability. Fortunately he also has an idea that will cover Torrance’s ass as well as his. There’s a Scotland Yard man called Inspector Murray (Michael Coles, returning from Dracula, A.D. 1972) who has some experience in matters akin to the goings on at Pelham House. If Torrance brought Murray onboard, Porter would no longer be able to shut the investigation down solely on his own authority.

What Murray learns from his initial meeting with Mathews and Torrance is alarming indeed. At Pelham House, Hanson witnessed what appeared to be a Satanic ritual of human sacrifice conducted by a Chinese woman identified as Chan Yang (Hardware’s Barbara Yu Ling). In attendance were five men of great power and influence: Porter, of course, whose responsibilities in the cabinet cover the whole national security apparatus, but also land magnate Lord Carradine (Patrick Barr, from The House of Whipcord and The Flesh and Blood Show), General Sir Arthur Freeborne of the Imperial General Staff (Lockwood West), and Nobel Prize-winning microbiologist Professor Julian Keeley (Freddie Jones, of The Man Who Haunted Himself and Dune). Hanson didn’t recognize the fifth participant in the rite, nor was he successful in photographing him, but he was of even more commanding demeanor than the others, and obviously used to getting his way even from them. If London harbors a nest of devil-worshippers with that kind of clout, then Murray wants to call in a real expert. With the colonel’s permission, Murray presents all of Hanson’s evidence to anthropologist and occult scholar Lorimer Van Helsing (Peter Cushing), the man who helped him crack the case of the hippy vampire-cult murders two years ago.

Van Helsing is appalled in general, of course, but what disturbs him most is the involvement of Julian Keeley. The two academics used to teach at the same university before Keeley left to start his own research foundation, and Lorimer still considers Julian a friend even though it’s been years since they last spoke. Van Helsing decides to begin by paying Keeley a personal visit, but the renewal of their acquaintance proves anything but pleasant. Julian has gone obviously batshit crazy under the dual pressures of overwork and fear, both somehow related not only to the Pelham House coven, but also to a collection of Petri dishes full of unsavory-looking microbial cultures in his laboratory. Sustained prodding from Van Helsing eventually elicits the astounding admission that the latter contain a new strain of Yersinia pestis that makes the original Black Death look like the common cold. Lorimer is in the process of soliciting an explanation for why his old friend would deliberately cultivate such a thing when one of those Viking bikers bursts in. The shot he fires at Van Helsing merely grazes his skull, but puts him out like a light long enough for the assassin to hang Keeley from the rafters with his own belt, and to abscond with all the custom-bred plague germs.

There was one other important detail that Van Helsing got out of Keeley amid all the jumbled, paranoid raving, which was that his deadline for developing the lethal new disease was November 23rd. The professor knows that date well; it’s the Sabbat of the Undead, one of the most ill-omened dates in the liturgical calendar of evil. It’s also, as the name suggests, of particular significance to vampires and their followers, which gives Van Helsing a hunch that he doesn’t like one bit. Paying a visit to the site of St. Barthold’s Church— the formerly holy ground where he had his showdown with Count Dracula (Christopher Lee, one last, begrudging time) two years ago— he finds the land built over with an office tower belonging to the corporate empire of reclusive industrialist D.D. Denham. And would you like to guess the names of the four men who sit alongside Denham on the board of directors for his companies? That’s right: John Porter M.P., Lord Carradine, General Sir Arthur Freeborne, and the late Professor Julian Keeley. With that in mind, do you suppose we have some idea now why Denham has never been photographed, and never permits himself to be seen in public? Obviously a swift return to Pelham House is warranted at this point, for the Sabbat of the Undead is just days away. Mathews, Torrance, and Murray go in armed for bear by British standards, accompanied on their mission by Van Helsing’s talented granddaughter, Jessica. (Stephanie Beacham was busy, so her old role went instead to Joanna Lumley, of Fanny Hill Meets Lady Chatterley.) The elder Van Helsing, meanwhile, goes to arrange a personal interview with D.D. Denham— who he’s quite sure will want to see him, reclusive temperament notwithstanding, if only the security guard in the tower block lobby would pass along his name.

A lot of the material that went into The Satanic Rites of Dracula ought to be likeable, assuming one can set aside any and every expectation one might have of what a Dracula movie should be. The tangled, genre-bending premise has a strong Brit-comics vibe, like a forgotten antecedent to The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen or a spinoff from “The Protectors” written by Warren Ellis. A suicidal Dracula scheming to take the entire human race down with him is something I’ve never seen before, and positioning him as a corrupt captain of industry restores, in a roundabout way, some of the class subtext that Hammer were usually leery of exploring in their vampire films. Deputizing Lorimer Van Helsing as an expert advisor to an ad-hoc government monster-fighting task force makes The Satanic Rites of Dracula something of a precursor to Hellboy as well, albeit with outside influences drawn from 1960’s spy movies rather than Bronze Age superhero comics. And on a related note, it’s nice to see Van Helsing, Inspector Murray, and Jessica coming together into a proper ensemble this second time around, especially now that Stephanie Beacham as been replaced by the far more capable Joanna Lumley. This movie even overcomes the prudishness that made The Devil Rides Out such a laughing stock. The titular rites have some genuine erotic heat to them, mingling horror and perversion in the previously taboo Continental European manner. Throw in an unfamiliar array of real-world shooting locations, and The Satanic Rites of Dracula becomes one of the few Hammer horror films to feel fully modern in a cinematic sense, instead of just adopting the trappings of a modern setting as a marketing gimmick.

None of that stuff really works, though, simply because The Satanic Rites of Dracula is so hopelessly, desperately cheap. You might expect the shift away from fabricated sets to disguise that, but instead it calls attention to it in whole new ways. For one thing, director of photography Brian Probyn seems at a loss for what to do with all this open space and natural light, giving the film a drab, home movie-ish appearance. But more importantly, London as seen here is weirdly empty, with nary an extra to be seen milling around anywhere. Colonel Mathews’s task force looks to be run on an absolute shoestring, with himself, Torrance, and Hanson supported only by a little-seen staff physician and a single secretary. I know the British government in the 1970’s was big on austerity, but this is ridiculous! D.D. Denham Industries fares even worse; despite the impressive size of his headquarters building, Denham apparently employs nobody but that one security guard in the lobby. At least the plague cult has its half-dozen Viking bikers and a quartet of vampire girls shackled in the basement of Pelham House. There are plenty of stories that you could tell on film successfully even with this paucity of background figures, but no movie threatening the human race with extinction can afford to look like the extinction event has already occurred.

The other fatal flaw in The Satanic Rites of Dracula is Christopher Lee. The man was quite simply done with this part by 1973— hell, he was done with it already in 1970, although back then at least he could still put on a show of giving a fuck. Lee has no such power left in this installment, which he very plainly appears in against both his will and his better judgment. It’s a bleak state of affairs when your Dracula movie benefits from having barely any Dracula in it. Now that I’ve seen The Satanic Rites of Dracula, I’m no longer surprised that Warner Brothers initially took a pass on distributing it in the United States. It would take four years and a resurgence of popular interest in the character thanks to the stage revival starring Frank Langella to change their minds.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact