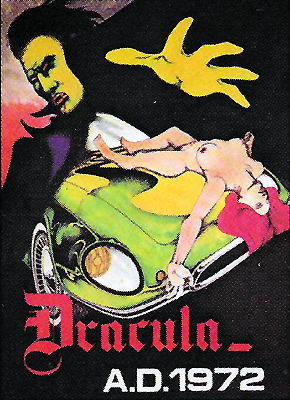

Dracula, A.D. 1972 / Dracula Today (1972) -***½

Dracula, A.D. 1972 / Dracula Today (1972) -***½

I’ve devoted a lot of effort over the years to complicating the conventional narrative that Hammer Film Productions lost the mandate of heaven in 1968. After all, any studio that can put out Hands of the Ripper, Twins of Evil, and Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde in a single year is obviously doing something right, especially when even its misfires are apt to be as interesting as Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb and Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter. But the notion of Hammer floundering their way to extinction as the genres that had been the company’s bread and butter evolved beyond them isn’t exactly wrong, either. When Rosemary’s Baby touched off an international craze for the occult, Hammer offered up The Devil Rides Out, adapted from a 30-year-old novel by the stodgiest “expert” on diabolism since the author of the Malleus Maleficarum. When 2001: A Space Odyssey and Planet of the Apes took sci-fi upscale, Hammer replied with Moon Zero Two, a tedious claim-jumper Western in outer space drag. And the erstwhile global trendsetters in horror had nothing to say at all in response to Night of the Living Dead, despite having released one of the best pre-Romero zombie movies as recently as 1966. But Hammer’s most pitiable post-’68 turkeys were gobbling in the coop marked “Edgy, Hip, and Sexy.” That’s where you’ll find The Horror of Frankenstein, a reboot so lame that it got de-booted four years later, and it’s also where you’ll find Dracula, A.D. 1972. Dracula, A.D. 1972 was Hammer’s clumsily literal attempt to modernize its long-running flagship franchise, and it manages to get wrong every single thing that American International got right with Count Yorga, Vampire two years earlier. It is, without credible rival, my favorite truly terrible Hammer film.

Dracula, A.D. 1972 begins, rather unexpectedly, in 1872, and in doing so, it formally defines the setting of the series in ways that had been only faintly implied previously. The Dr. Van Helsing (Peter Cushing, revisiting the role for the first time since 1960) who is currently battling Count Dracula (Christopher Lee, looking more exasperated than ever to be playing the part for this studio) atop a speeding carriage in Hyde Park is not the one we remember from Horror of Dracula and The Brides of Dracula— now retroactively identified as Charles Van Helsing— but rather his son, Lawrence. That places the action of those initial Hammer Dracula pictures quite early in the 19th century, and puts even this prologue fully a generation before Bram Stoker’s intended temporal setting. In any case, Lawrence’s encounter with that most masterful of all master vampires goes considerably worse for him than his dad’s did all those years ago. Although he succeeds in staking Dracula amid the wreckage of the coach after the horses break loose and run it off the road, Van Helsing dies, too, of injuries sustained during the crash. And because the vampire’s dust is gathered up afterwards by one of his disciples (Christopher Neame, from No Blade of Grass and Lust for a Vampire) and hidden in the unconsecrated section of the very churchyard where Van Helsing is laid to rest alongside his illustrious father, it’s a safe bet that the world hasn’t seen the last of Count Dracula even now.

100 years later, a disapproving upper-class matron right out of a Carry On film (Screamtime’s Lally Bowers) is throwing a party, and it isn’t going well. The old dame magnanimously allowed her twerp son, Charles (Michael Daly, of The Dirtiest Girl I Ever Met), to secure the entertainment, and the original plan was for him to hire the Faces. Hammer didn’t actually have Rod Stewart money in 1972, though, so instead we get Stoneground, a band that sounds like “Gimme Shelter” ate paint chips on the regular as an infant, comprised of the eleven squarest hippies in all California. Meanwhile, on the diegetic front, Stoneground have drawn a horde of long-haired, ill-behaved party-crashers who have overwhelmed the legitimate guests in social impact, if perhaps not quite in sheer numbers. It’s a bit of a game, you see. The rowdy youth all know perfectly well that someone will call the cops on them eventually, and the object is to time their escape as near as possible to exactly one minute before the first bobby on the scene comes knocking. Look closely, though, and you’ll see that one of the hippy intruders— Johnny Alucard, he calls himself— looks exactly like the chap who salvaged the dust of Dracula’s corpse back in 1872. And as if that weren’t enough to mark him as a more serious form of trouble than his fellows, Johnny makes a big production of committing a single act of pointless, mean-spirited vandalism on his way out the door.

The following day, at a coffee house called the Cavern, Johnny proposes taking his friends’ recreational misbehavior up a notch. There’s a church he knows that’s slated for demolition, which naturally means that the building and its grounds had to be deconsecrated. Wouldn’t it be a kick to sneak into the building some midnight soon, and perform a black mass to finish the job? Laura (Caroline Munro, from Don’t Open Till Christmas and Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter), the member of the group most fascinated by the aesthetics of transgression, jumps at the idea, and Joe (William Ellis), whose appetite for sacrilege extends to dressing all the time like a mendicant friar, needs little more persuasion. Bob (Pip Miller, of Three Dangerous Ladies), Gaynor (minor British soul singer Marsha Hunt, whose other turns as an actress include The Sender and Howling II), and Anna (Janet Key, from And Now the Screaming Starts and The Devil Within Her) are hesitant, but willing to hear Johnny out. Only Jessica Van Helsing (Stephanie Beacham, of The Nightcomers and Inseminoid), the great-great-granddaughter of the ill-fated Lawrence Van Helsing, remains convinced that the undertaking is a bad idea. Jessica is by no means an expert on the occult, but her guardian grandfather is, and the old man has instilled in her a healthy wariness toward mucking about with the supernatural. (Will any of you be surprised to see that Jessica’s grandpa, Lorimer Van Helsing, is played by Peter Cushing, too?) Still, even she eventually goes along to get along— but not without doing a bit of preparatory reading in her grandfather’s study.

You know what’s coming, of course. Not only is Johnny Alucard’s black mass the real deal, but its primary purpose is to resurrect Count Dracula. There’s a second purpose, too, so far as Dracula himself is concerned, but its importance seems not to have been adequately conveyed from father to son down the Alucard line over the preceding century: the count wanted it to be Van Helsing blood that restored him to life. Johnny has to wing the details of the ceremony, though, since he isn’t exactly working with a trained coven here. Laura insists that she be the one on the altar of sacrifice (’cause the whole thing is just a blasphemous lark, right?), and the blood that Johnny spills into the chalice full of dehydrated Instant Dracula comes from his own wrist. Even that is enough to provoke a four-alarm freakout among the other hippies, all of whom save Laura (who struggles paralyzed on the altar by the force of Johnny’s conjuring) flee the church like their asses were on fire. Dracula is annoyed by the lapse of protocol when he finishes reconstituting himself (and Christopher Lee is even more annoyed to be back in the movie), but there are worse breakfasts to wake up to than Caroline Munro.

Laura’s exsanguinated body is discovered the next morning by some kids who are in the habit of playing on the old church’s interestingly dilapidated grounds. Her identity is established easily enough thanks to the paper trail of a recent drug bust, and soon Inspector Murray of Scotland Yard (Michael Coles, of I Want What I Want and Dr. Who and the Daleks) is sniffing after known associates of the dead girl. Murray is intrigued to see Jessica Van Helsing show up on that list, because he slightly knows her grandfather. Lorimer Van Helsing has had occasion to assist the police force from time to time, and Murray meant to talk to him anyway on the theory that there might have been a cultic aspect to Laura’s murder. The draining of the victim’s blood has rather different associations for Van Helsing than it does for the inspector, however. Sure, there could be a hippy murder cult on the loose in London, like that terrible business in America a few years back, but the professor sees an even more horrid possibility that Murray isn’t yet ready to dignify with even tentative consideration. Blood-mad hippies are bad enough, but what if Laura’s killer was instead a vampire?

Van Helsing will spend the remainder of the film trying to convince Murray that that isn’t an insane idea. Johnny Alucard will spend the rest of the film feeding hippies who are conspicuously not Jessica to Dracula. Jessica and Murray, in their respective ways, will spend it trying to figure out who keeps killing the girl’s friends and why. And Dracula will just grow increasingly vexed with Johnny’s inability to follow instructions, even after he transforms the lad into a vampire. Eventually, Jessica mentions to her grandfather the name of her least favorite pal from the Cavern scene, and the professor notices what happens when you reverse the letters in “Alucard.” The old man knows exactly what he must do at that point, with or without the help of Inspector Murray.

I used to be with it, but then they changed what “it” was! Now what I’m with isn’t “it” anymore, and what is “it” seems strange and scary to me. It’ll happen to you! |

—Abe Simpson |

The fascinating thing about Dracula, A.D. 1972 is how unnecessary it was. That extraordinary run of Hammer movies in 1971 adds up to a sort of alternative vision for horror in the 1970’s that could have kept the studio relevant throughout the decade by competing with Continental Europe instead of Hollywood. There’d have been a price for that, to be sure. A Europe-oriented Hammer would necessarily have sacrificed the leading role in global horror cinema which the firm’s leadership had grown accustomed to playing, striving instead for dominance of a niche market where Britain’s stronger film-censorship regime would place them at something of a disadvantage. But in point of fact, Hammer were in the process of losing that leading role anyway, as the Hollywood studios learned how to make B-movies on A-budgets, while the independents pursued extremes of transgression that left Hammer’s most shocking prior excesses in the dust. Be that as it may, the point is that movies like Vampire Circus and Hands of the Ripper got the mood of the new decade right, however traditional their subject matter appeared on the surface. Dracula, A.D. 1972, in contrast, is a pathetic exercise in zeitgeist-chasing, doomed as such undertakings invariably are to looking instantly dated and foolish.

Crucially, Dracula, A.D. 1972 doesn’t even seem sure of which zeitgeist it’s trying to catch. Witness, for starters, the jarring transition between the wailing pseudo-funk cue that plays over the opening credits, risibly reminiscent of the era’s James Bond themes (a model that had itself entered a period of scrambling after receding relevance), and the gospel-flavored wannabe swamp rock served up by Stoneground during the ensuing party scene. More seriously, although the filmmakers clearly had some passing familiarity with hippies, mods, and Teds, they seem not to have understood that those were three separate and often mutually antagonistic youth tribes. The overwhelming impression is that Dracula, A.D. 1972 wants to show London swinging in ways that it hadn’t swung for some years. And that’s before we even begin to consider the specifics of Johnny Alucard, the film’s central avatar of Youth Run Wild. Functionally, he’s an update of Ralph Bates’s limpdick libertine from Taste the Blood of Dracula, which is an ill omen all by itself. But then Christopher Neame makes it so much worse by attacking the part with a Poundland Malcolm McDowell energy, drawing an untenable comparison that elevates an already questionable characterization into one of the all-time wankers of cinematic villainy. Also, “Alucard” was cheesy enough in Son of Dracula. The way it’s handled here, with Van Helsing painstakingly solving the childishly simple anagram on a scrap of note paper in his study, is like cave-ripening the cheese under a pile of manure for the intervening 29 years.

But what makes Dracula, A.D. 1972 so compelling in its lousiness is how misguided it is in trying to update the Dracula franchise specifically in so crudely simplistic a manner. I’ve talked about this before in other reviews, but one of the defining traits of Hammer horror from 1957 through 1968 was its implicit acceptance of the old-fashioned morality that it took such glee in flouting. Vampires, maniacs, mad scientists, and devil-worshippers might run amok from time to time, but God was in his heaven, and could be counted on to guide the hands of those with the power to thwart such outbreaks of evil. No two characters more clearly personified that dynamic than Count Dracula and Dr. Van Helsing, even though they met face to face in but a single film. In the 70’s, though, horror movies in general stopped offering any such easy assurances. Not only was it suddenly possible for evil to triumph, but more frightening still, it was possible for chaos to triumph as well. In the 70’s, the heroes of horror films could be not merely damned, but flat-out fucked. What made Hammer’s 1971 lineup so promising was its readiness to engage with that new paradigm, even if the films mostly stopped short of embracing it. Note, however, that none of those were Dracula pictures. Unburdened by Horror of Dracula’s expectation of a moral universe, they were free to posit a dreadfully amoral one at will. To be sure, there was one Dracula installment— Taste the Blood of Dracula— that flirted with the 70’s horror mindset, but it critically lacked Dr. Van Helsing, or indeed any analogous character, to oppose the vampire from a position of patriarchal strength and authority. Dracula, A.D. 1972 blows that completely. Not only does it bring back Van Helsing after a four-sequel absence, but it recasts his struggle with Dracula into a generational epic. Nothing could be more starkly at odds with the genre’s prevailing mood than that, nor could anything call more insistent attention to the generation gap that Hammer was trying to jump by making a modern-day Dracula flick in the first place.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact