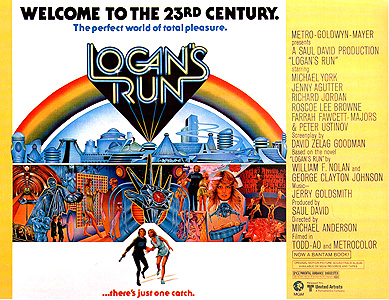

Logan's Run (1976) **½

Logan's Run (1976) **½

I just turned 29 on Monday. I probably shouldn’t think of it as that big of a deal, but I can’t help myself. Most of my friends aren’t even 25 yet, and the social scene in which I operate is avowedly youth-oriented— 18-year-olds all over the place. Not only that, I’ve always felt more than a little sympathy with the old 60’s student-radical slogan, “Never trust anyone over 30.” Yeah, well that’s going to mean me sooner rather than later, and I can’t say I like the idea. Don’t misunderstand me, now. It’s not that I think I’m old, for I most certainly am not. But turning 30 definitely means, in some socially significant way, that you’re not young anymore. When you come across the phrase “the youth” in a sociological context, you might not know where exactly the person using it has drawn their boundaries, but you can be damned sure they’re not talking about anyone 30 or older. It also seems to me that a person needs to undergo some sort of paradigm shift sometime between their late 20’s and mid-30’s if they’re going to stay sane during the rest of their life; otherwise, their way of relating to the world around them is going to fall farther and farther out of sync with the realities of their situation, and that can’t be a healthy way to live. The thing is, though, that the prospect of making that paradigm shift is at least as scary as the alternative, and I almost think I’d rather take my chances with a lifetime of cognitive dissonance. It’s a lot to think about, and it’s been weighing pretty heavily on my mind of late. Not heavily enough, however, to stifle my impulse to black humor. That stays with me no matter how serious things look, and I knew already a good, long while ago how I was going to celebrate this final birthday of my 20’s. I was going to watch Logan’s Run.

Logan’s Run was a latecomer in the wave of dystopian sci-fi that kicked off with Planet of the Apes in 1968 and was finally broken by Star Wars and its spawn just less than ten years later. Like the great majority of its contemporaries— Silent Running, Soylent Green, maybe even The Omega Man; I’m sure you can think of a few more all by yourself— it extrapolates in a rather odd (not to say hysterical) direction from the turmoil of its time, and comes up with a vision of the future just a little too grandiosely bleak for its creators to quite get a handle on. Logan’s Run covers all the usual apocalyptic bases, including nuclear war, overpopulation, and ecological collapse, but the piece of turmoil that seems to inform it the most strongly is that old line about not trusting people over 30. As is usual for films of this type, an opening crawl explains that civilization as we know it was destroyed sometime in the not-too-distant future by the Catastrophe. Just what the Catastrophe was is left a bit vague, but war, pollution, disease, and the rest of the standard horsemen of the sci-fi apocalypse were all evidently involved at some level or other. By the year 2274, all that remains of humanity lives concentrated in a single largish city, insulated from the hostile elements by a network of airtight geodesic domes. The city is more or less entirely automated, and the few million people who live within it lead lives given over entirely to leisure. It should already be obvious that, if this situation is going to persist for long, the city’s population must be strictly controlled. Otherwise the steadily increasing demands on the automated infrastructure would eventually overwhelm the entire system. Thus it is that no inhabitant of the city is permitted to live beyond his or her 30th birthday. Each citizen is fitted at birth with a crystalline lifeclock in the palm of the left hand, and with each transition of age the device changes color, letting everyone see just how much longer its owner has to live. When the citizen comes to within a few days of his or her Lastday, the lifeclock begins flashing red as a signal that the time for death has come. Now this would be a pretty bitter pill to swallow as is, so the long-dead architects of the post-Catastrophe order did what humans have always done in the face of unendurable but unavoidable realities, and invented a religion. According to this faith, Lastday is not the occasion of death, but of Renewal. Through the ritual of the Carousel, the spirit of the departing citizen is passed on into the body of a newborn infant, the old body being incinerated by the machine that gives the rite its name. The truth is, it seems neither any worse nor any more inherently delusional to me than any of the religions people have concocted to make life easier to face in the real world.

But, again as in the real world, the church of Renewal has its atheists to contend with. These misfits don’t buy the official story, and focus instead on the Carousel ritual’s destruction of perfectly healthy people who could live to be who knows how much older if left to their own devices. Not believing in Renewal, they try instead to escape from the city and hang on to the life they already have. These people are known as runners, and in order to deal with the threat they pose to the smooth functioning of society, the city employs a police force called the Sandmen to track them down and terminate them. Our central character, Logan 5 (Michael York, from The Island of Dr. Moreau and the 1983 TV version of The Phantom of the Opera), is one of these Sandmen, and very early on, we see him and his partner, Francis 7 (Richard Jordan, of Dune and Solarbabies), gleefully hunting down a runner and killing him with exceptionally cheesy rayguns which strongly suggest that somebody in this movie’s special effects department was a big fan of The Wild, Wild Planet. One gets the impression that this is pretty much an ordinary day at the office for a Sandman, but Logan is about to be handed an assignment that is anything but ordinary. The computer from which all of the Sandmen take their orders has become concerned about the cumulative effects of a slow but steady trickle of runners who have been slipping out of the city— 1056 of them to date. Word on the street is there’s a place called Sanctuary out in the wilderness somewhere, where the escapees congregate, and the computer thinks it would be a nifty idea to have one of its Sandmen go undercover as a runner, infiltrate Sanctuary, and destroy it along with however many of those 1056 runners are still hanging out there. Why it picks Logan to do the dirty work is anybody’s guess— hell, at 26, he isn’t even old enough to be convincing as a runner yet! Utterly untroubled by this complication, the computer simply accelerates Logan’s lifeclock to the flashing stage, and sends him on his way.

If you ask me, the Great Computer isn’t very smart, as Great Computers go. When you want somebody to do an unusual and difficult favor for you, how do you approach the person in question? Exactly— you kiss their ass big-time. But does the computer do that? No. Instead, it refuses to answer Logan’s questions, dismisses his ideas on the subject of Sanctuary out of hand, and gives him the runaround on the question of whether or not he’ll be getting his four years back after his mission is accomplished. All in all, it’s enough to make Logan— always something of a questioner— wonder if maybe the runners aren’t right after all. His thinking progresses yet farther in that direction when he meets Jessica 6 (Jenny Agutter, from Dominique Is Dead and An American Werewolf in London), a girl a year younger than him who is extremely skeptical about that whole Renewal thing. At first, Logan figures Jessica is a safe bet for getting him out of the city and pointed in the direction of Sanctuary, but after duplicitously befriending her, he gradually arrives at the conclusion that she and her runner friends have the right idea. Thus when Logan leaves the city’s confines with Jessica on the hunt for Sanctuary, he’s running for real. Not only that, his old buddy Francis is hot on his trail.

Really, I could stop right here, and you’d be able to make up most of the next hour for yourself. True to form, Logan and Jessica end up wandering among the overgrown ruins of famous landmarks— the Capitol Building, the Lincoln Memorial, and the Washington Monument, in particular. They meet a descendant of survivors from Pre-Catastrophic time (Peter Ustinov), who tells them about the way life used to be lived in the old days. They gradually discard the now-irrelevant mindsets drilled into them by their Huxleyan upbringing in the city, reverting to what your more hopeful writers of dystopian sci-fi would have us believe is the natural outlook of humankind. And of course, they have a nice little showdown with Francis 7, who catches up to them (a little the worse for wear) in the Capitol lobby. Just about the only things you won’t see coming are the encounter with the suck-ass robot in the ice cave (!) and what happens when Logan gets it into his head to return to the city with a real, live old man to convince his former neighbors that life needn’t end at 30 after all.

Most people who see Logan’s Run today (at least those who do not inexplicably regard it as a bona fide sci-fi classic) tend to harp on the limitations of the special effects and set design. They have a point. Logan’s Run was pretty much the last big-budget Hollywood sci-fi flick of the pre-Industrial Light and Magic age, and its 60’s-style technical esthetic hasn’t aged well, looking especially silly in a film that wants so badly to be taken seriously. I mean, how can you not snicker at a movie in which the ultra-high-tech City of the Future is really just a series of tacky miniature models interspersed with interior shots filmed at a shopping mall in Dallas? I’m well accustomed to that sort of thing, though, and I mainly find fault with the movie elsewhere. The real problem with Logan’s Run is that writer David Zeelag Goodman and director Michael Anderson never adequately answer the biggest challenge that confronts any creator of dystopian science fiction. Since its inception, the dystopia has been an inherently polemical subgenre; nobody ever writes one except to make a point, and the aim is usually to inspire the reader/viewer to think about where society is headed, and ideally to take action in order to prevent whatever bleak vision of the future is involved from coming to pass. That bleak vision must therefore be a plausible one, at least at some level, or the dystopia will be dismissed as fanciful by the audience. On the other hand, it is easy to go too far in that direction, presenting a grim future that seems both inevitable and irreparable. Happy endings should be avoided, if for no other reason than that a global totalitarian regime that can be toppled, say, by one good sports riot will look more hapless than threatening to any remotely thoughtful audience. But because most people respond better to hope than to despair, it takes a talent almost equal to Orwell’s to craft a suitably inspiring dystopia that is as relentlessly hellish as 1984. The vision of the future offered up by Logan’s Run has a certain internal logic to it, and the movie works fairly well during the first hour, when exposition is the first order of business. The run itself, however, is a rather lifeless affair, and the ending races gleefully into absurdity as an entire social order collapses because of a single fatal exception error. (Evidently the Great Computer is still running Windows Millennium Edition…) Still, it’s a hell of a lot better than Rollerball.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact