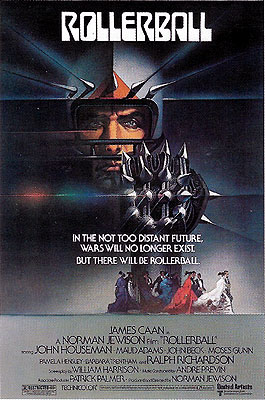

Rollerball (1975) -**Ĺ

Rollerball (1975) -**Ĺ

The 1970ís were a big decade for dystopian sci-fi movies; virtually every stratum of the movie industry was involved in the efflorescence, and nearly every approach was tried at least once. There were low-budget independents like THX 1138 and major-studio blowouts like the Sequels of the Apes. The canny quirkiness of A Boy and His Dog was counterbalanced by the witless buffoonery of Loganís Run. From the nightmarish bleakness of A Clockwork Orange to the sarcastic irreverence of Death Race 2000 to the visceral hindbrain thrills of Mad Max, every imaginable mood and tone was employed. And smack in the middle of it all was Rollerball, a movie whose creators donít seem to have been quite sure what they wanted it to be. On the basis of director Norman Jewisonís post-mortem comments, it sounds as though he thought he was making a serious statement about an all-too-likely futureó Brave New World, 70ís style. But the movie he actually made owes far more to Roger Corman than it does to Aldous Huxley, and the absurdity of the story it tells is only intensified by Jewisonís impassioned, polemical tone.

Howís this for a vision of the future? In the year 2018, there are no more nations, states, or traditional political authorities of any kind. The entire world is controlled by a single vast corporation, with subsidiary companies in charge of such specialties as energy, housing, communications, etc. The Corporation provides for every need and want of every man, woman, and child in the world, in exchange for which service the entire world population entrusts the Corporate Directorate with absolute power. The result is a society entirely given over to consumerism and the hedonistic pursuit of leisure. So far, weíre on the right track, especially when this premise is viewed through 21st-century eyes. Rollerballís Huxleyan credentials sound impeccable on the surface, and such details as the legality and ready availability of powerful, fast-acting narcotics (soma, anyone?) and socially encouraged sexual promiscuity (the latter only implied) further underscore the comparison. But unlike the controllers of Huxleyís Brave New World, the Corporation has not yet thought to biologically engineer and scientifically condition the human race so that everyone fits perfectly into their assigned roles. Thus there is a pressing need for the release of social tension, and the outlet the Corporationís Directors have settled on is an ultra-violent team sport called Rollerball. This is where the ridiculousness starts to creep in. Imagine, if you will, a hybrid of roller derby, basketball, and Thai boxing, with guys on motorcycles thrown into the mix for added flavor. A sport, no less, whose avid fans could teach the football hooligans of Great Britain or the circus partisans of sixth-century Byzantium a thing or two about rowdiness. That, more or less, is Rollerball. Itís also the sort of thing that simply cries out not to be taken seriouslyó not that that stops Norman Jewison, mind you!

As the movie begins, the top-ranked Rollerball team on Earth is based in the unlikely city of Houston, in what used to be Texas. Houstonís team captain, known only as Jonathan E. (James Caan, from Alien Nation and Misery), is probably the best player the sport has ever seen. Heís set more records in his ten-year career than most of his peers even realized were there to be set, and he is a household name all over the planet. In fact, so great are his lifetime contributions to the sport of Rollerball that the Corporation plans to honor him with a special multivision (itís like television, but with four screens) documentary on his career. But something fishy is going on. Shortly after a Corporation executive named Bartholomew (John Houseman, from Ghost Story and The Fog) announces the good news to Jonathan and his teammates in the locker room following their crushing victory over Madridís Rollerball team, he asks the superstar to come see him in his office for a private chat. To Jonathanís astonishment, the Corporation has decided that he needs to retire, and that his scheduled appearance on multivision would be the ideal time for him to make his retirement public. This is all the more baffling because there are only two games left in the season, and Houston is a shoo-in for a slot in the championship tournament. At the very least, youíd expect the suits to want him to stick around long enough to lead his team to another championship win. When Jonathan is reluctant to agree, Bartholomew tells him he has some time to decide yet, but to think about it, and to think about his duty to his Corporation and to society.

This isnít the first time the Corporation has come in and fucked with Jonathanís life, as it turns out. Some six months ago, an executive decided he wanted Jonathanís wife, Ella (Maud Adams, a semi-respectable actress whose career had sunk so far into the toilet by the turn of the 90ís that she actually thought it was a good idea to appear in Silent Night, Deadly Night 4: Initiation), and before Jonathan knew it, she was gone, replaced by a new wife named Mackie (Pamela Hensley, from Buck Rogers in the 25th Century). Jonathan is still upset over it, and his resentment at that earlier imposition makes him even less inclined to go along with the Corporationís plans to put him out to pasture than he would have been anyway. Fortunately for him, he has one good friend in the Executive caste: Cletus (Moses Gunn, from Shaft and Firestarter), the man who recruited him as a Rollerballer ten years ago. With Cletusís help, Jonathan is sure he can figure out who wants him gone and why.

But the Corporation has ways of getting what it wants, and the more Jonathan resists, the more pressure is brought to bear on him. First, Mackie is taken away from him and given, like Ella before her, to an executive; her replacement, Daphne (Barbara Trentham of Death Moon and The Possession of Joel Delaney), is obviously in on the plot to coerce his retirement. Then the Rollerball commission starts changing the rules to make the game more violentó almost as though somebody is hoping Jonathan will get himself killed on the track in the upcoming game against the famously vicious Tokyo team. Jonathan doesnít, naturally, and Houston puts Tokyo out of the running just as surely as it had Madrid, but Jonathanís best friend, Moonpie (The Bat Peopleís John Beck, who looks an awful lot like a young Jesse ďthe BodyĒ Ventura), is knocked into a persistent vegetative state by a karate punch to the back of the head during the match.

So whatís this all about, you ask? Well, believe it or not, the Corporation is acutely afraid of Jonathan. His fame, his skill, his initiative, his knack for leadershipó all of these things are terribly alarming to a totalitarian clique that keeps itself in power by conning the people into forgetting that they are individuals, each with their own interests and desires. Every time the Directors hear the stadium crowds chanting Jonathanís name (notice that the fans of the other teams only ever chant the names of their cities), a little shiver shoots up their spines. Sure, there hasnít been a sports riot big enough to threaten a government since the Nika Revolt back in A.D. 532, but you just never know, and totalitarians throughout history have always preferred to be safe rather than sorry. So when Jonathan still hasnít stepped down by the time of the championship match, the Directors see to it that the official rules of Rollerball are changed again, this time in such a way as to make it all but inevitable that the competing teams will have to play to the last man in order to win. Of course you know how this is going to work in practice. When at last itís down to just Jonathan and a single player from the New York team, our hero pointedly settles for incapacitating his opponent rather than finishing him off, then skates the ball over to the goal and slams it in, finishing with a victory lap as the stunned crowd chants his name with mounting fervor. Could that be a revolution I hear approaching?

Well no, actually. It couldnít be. And therein lies part of the secret to Rollerballís failure as a serious dystopia. The great onesó Brave New World and 1984 especiallyó derive their power from their explicit acknowledgement of the near-invulnerability of totalitarian regimes to individual resistance. It took the bloodiest war in human history to topple Hitler, Mussolini, and the military government of Imperial Japan. It took 45 years of economically unsustainable cold war to bring down Russian communism. Thereís just no way the sort of regime this movie posits is going to be susceptible to attack from a fucking sports hero! At best, Jonathanís courageous stand could plant psychological seeds that might bear fruit in a generation or two, when the Corporationís rule becomes stagnant, senile, and inefficient, as all governments must eventually. Even if the essential silliness of a movie that revolves around a futuristic bloodsport played on roller skates and motorcycles hadnít already fatally compromised Jewisonís high-minded artistic aims, this jarring failure to follow through on the implications of the story would have. In interviews sparked by the impending release of the Rollerball remake, Jewison attributed his versionís miserable performance at the box office to the unwillingness of people in 1975 to believe that corporations would ever become powerful enough to transcend, challenge, and ultimately replace old-fashioned political entities, but I think the man is merely flattering himself. No, it seems far more likely to me that Rollerball tanked because, for all its aspirations to philosophical significance and sociopolitical relevance, it actually comes across as just a big, dumb movie about guys kicking the shit out of each other on roller skatesó a futuristic, masculinized version of The Unholy Rollers, with no sex and a Cassandra complex. Itís still fun, but youíd be much better served by watching Death Race 2000 instead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact