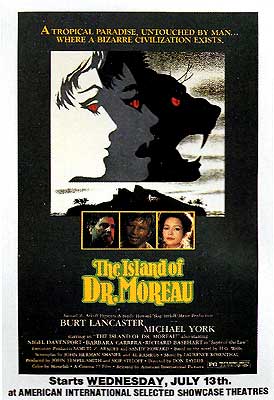

The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977) **

The Island of Dr. Moreau (1977) **

American International Pictures had taken a huge risk in 1960, when they bankrolled Roger Corman’s The Fall of the House of Usher to the tune of a quarter-million dollars. That was more than four times the budget of the typical AIP production, and not too far short of what the major studios would spend on their cheapest films. It turned out to be a smart investment, however, and the next five years saw the studio enjoying success after success with similarly priced movies, including seven more Corman-Poe outings and a comparable total of beach party flicks. It was enough to give AIP bosses Samuel Z. Arkoff and James H. Nicholson the hope of one day developing their firm into a “ninth major.” (The eight major studios recognized in those days were MGM, Paramount, Warner Brothers, 20th Century Fox, Universal, Columbia, and United Artists, plus the putrefying, marginally animate corpse of RKO.) Those hopes were never quite realized, however. The closest AIP came to that coveted ascension was in the late 1970’s, when a string of glossy, stuffy genre pictures with seven-figure budgets achieved a shabby approximation of the mainstream Hollywood look, but did nothing for the studio but to open a sucking financial chest wound that would ultimately force Arkoff (Nicholson was dead by then) to merge with Filmways— which would itself be gobbled up by Orion Pictures a few years later. The Island of Dr. Moreau is an early product of that final, calamitous bid for respectability, and a fine illustration of why it was such a bad idea. Clunky and backward-looking, it mistakes timidity for class while misjudging the source of Island of Lost Souls’ enduring appeal. And despite positioning itself as a more faithful adaptation of the source novel than its famous predecessor, it manages to justify its existence only when it diverges most sharply from both.

This version dispenses with the convoluted business whereby the protagonist— here called Andrew Braddock (Michael York, from Logan’s Run and an early-80’s TV take on The Phantom of the Opera)— becomes a double castaway, streamlining the opening so that his lifeboat simply washes up directly onto the shore of the titular isle. Braddock initially had two companions aboard the craft, but one died of thirst shortly before they landed, and the other is killed by— well, something— while Andrew forays into the jungle in search of food and water. What appear to be the same somethings pursue Braddock, too, but he survives being caught. In fact, the next thing he knows, he’s coming awake in a comfortable bed, in a somewhat less comfortable villa. Evidently he’s been under the care of a man named Montgomery (Nigel Davenport, of Phase IV and No Blade of Grass), who enigmatically remarks that he used to be a doctor. Andrew can expect to remain in Montgomery’s company for some time even after he’s fully recovered, too, because the island is far from any regular shipping routes, and is visited only every two years by a steamer bearing supplies that cannot be grown or manufactured locally.

The villa belongs to Montgomery’s employer, Dr. Paul Moreau (Burt Lancaster), an eccentric and reclusive biologist. In addition to Montgomery, Moreau’s household includes a very pretty but almost feral girl called Maria (Embryo’s Barbara Carrera) and a host of peculiarly ugly domestic servants headed up by M’Ling (Nick Cravat, who played William Shatner’s gremlin in a famous episode of “The Twilight Zone”). Braddock plausibly takes M’Ling and his staff for natives of the island, but Moreau says he came by Maria as a foundling somewhere in the South Seas, and raised her as his own daughter ever since. Those acquainted with Island of Lost Souls will naturally assume that she’s really this remake’s equivalent to Lota the Panther Girl, especially after Moreau starts encouraging Braddock and his foster daughter to become friends That’s nothing but a fakeout, however, and the developing relationship between Andrew and Maria serves mainly to eat time until the filmmakers feel they’ve woven an adequate veil of mystery around the faintly glimpsed creatures, seemingly manlike but also somehow bestial, that are forever skulking about the forest.

The latter, of course, are the results of Moreau’s research, animals which he has elevated to a semblance of humanity via some nebulously defined program of gene therapy. There are dog men and cat men, pig men and ape men, bear men and bison men, all dwelling in a cave system at the center of the isle under the leadership of an ovine sort of creature called the Sayer of the Law (Richard Basehart, from Mansion of the Doomed and The Satan Bug). M’Ling and the rest of the domestic servants are manimals, too, but it’ll be a while yet before Braddock makes that connection. He learns about the project when he stumbles upon a work in progress (David Case, of Enter the Devil and The Boy Who Cried Werewolf) in Moreau’s lab, and leaps to a conclusion exactly opposite to the real state of affairs. In getting the doctor’s work backwards, though, Andrew has actually caught a glimpse of his own fate. You see, there’s a rather serious flaw in Moreau’s man-making process, one which he remains unable to eliminate no matter how he tries. Sooner or later, his creatures always revert gradually to what they used to be, and although Moreau has found ways of retarding the transformation back to animal, he can’t stop it. But now with Braddock on the island, Moreau has a new idea. What if he were to ply the reverse of his treatment on the castaway? Surely the change would be no more permanent than that of the manimals, and when Andrew regained his humanity, his memories of the experience could offer vital clues to what Moreau’s been doing wrong. Naturally, Moreau doesn’t bother soliciting Braddock’s opinion of this new line of research. I mean, if he asked for Andrew’s permission, he might not get it— and where would that leave him?

AIP would have done this so much better in 1973. More than anything, The Island of Dr. Moreau suffers from a self-defeating determination to be respectable, to prove that its studio was no longer the same outfit that made Coffy, Savage Sisters, and Hell’s Angels on Wheels. Gone is the icky bestiality angle that so appalled H. G. Wells when he heard about Island of Lost Souls (although the early ambiguity regarding Maria’s true back-story is a clear allusion to it). Gone too is the decadent sadism of Charles Laughton’s Moreau; Burt Lancaster’s interpretation is closer to the novel’s vision of a man so wrapped up in his work that he’s simply lost sight of its moral dimensions. The character designs for the manimals are more plausibly animalistic than those of the 1933 version, but at the same time less horrifying. The object seems to have been more to inspire Planet of the Apes-like awe at the makeup department’s prowess than to induce the shivers due an abomination against nature. And the overall vibe is “starchy adaptation of a classic piece of literature” rather than “update of a notorious but little-seen highlight of the first Hollywood horror boom.” The Island of Dr. Moreau is one of those vanishingly rare cases when a 1930’s fright film is not just better than its 70’s remake, but also more transgressive, more psychologically astute, and more genuinely disquieting.

The remake does begin justifying its existence somewhat when Moreau goes to work on Braddock, however. The loss of self Andrew faces, his helplessness in the absence of any plausible escape route from the island, the chilling ease with which Moreau shifts from generous if reluctant host to implacable tormentor— all that stuff is much more effective than anything we’ve seen in the preceding two acts, which is rather ironic considering that it owes more to the intensely silly The Twilight People than to any legitimate prior interpretation of this story. The battle of wills between Braddock and Moreau, in which the former seems to resist the transformation into an animal as much to deny the latter the knowledge he seeks as for any of the more immediately obvious reasons, is the only aspect in which The Island of Dr. Moreau approaches the perceptive psychodrama of Island of Lost Souls. Braddock’s alteration is also a clever way of forcing audience empathy with the animals Moreau has experimented upon, a point on which most Moreau films come up short. Other adaptations and knockoffs seek to horrify primarily with the perversion of nature that the manimals represent; to the extent that the creatures’ subjective experience is an issue, it’s generally with regard to their post-operative plight as something neither truly human nor truly beast. So far as I’ve seen, only Terror Is a Man deals seriously with the suffering of the transfigured animal as an animal. But by placing Andrew literally in the animal’s position, this version belatedly shifts our attention toward what it must have been like for all those bears and wolves and whatnot, even if it hasn’t given us much cause to consider them previously. It’s the best, smartest thing The Island of Dr. Moreau does, and I just wish the movie had gotten around to it sooner.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact