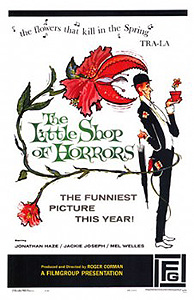

The Little Shop of Horrors (1960) ***½

The Little Shop of Horrors (1960) ***½

This won’t come as much of a surprise to anyone who’s seen it for themselves, but the original version of The Little Shop of Horrors (which has sadly been eclipsed by the big-budget musical remake from 1986) was made entirely on a lark. Roger Corman had been able to finish A Bucket of Blood in record time, and the experience got him wondering just how quickly he could crank out a movie. The cast and crew of A Bucket of Blood hadn’t dispersed yet, and one of the other producers in the building where Corman rented an office had recently mentioned that one of his movies had just finished shooting, but that the main set for it hadn’t yet been demolished. Corman talked his neighbor into leaving the set standing for another week, put his screenwriter buddy, Charles Griffith, to work on a script that could be shot on that set in a William Beaudine-worthy two days, and told everyone from his Bucket of Blood team that they had another job if they wanted it. The result was a surreal horror farce that plays like it was ad-libbed over the course of a wild, weekend-long bender.

Hidden in the depths of an unidentified city’s Skid Row is a flower shop belonging to one Gravis Mushnik (Mel Welles, from The Undead and Attack of the Crab Monsters). Mushnik’s is, as you might imagine, not exactly a flourishing business. Indeed, if it weren’t for regular customers like Sadie Shiva (Leola Wendorff)— one or another of whose relatives seems to need a funeral just about every day— it’s entirely possible that old Gravis would have to hang it up. Naturally, Mushnik’s staff is small. He employs a somewhat bubble-headed assistant named Audrey Tulguard (Jackie Joseph, who was later a voice-actress on “Josie and the Pussycats”), and a hapless, incompetent stock boy named Seymour Krelboyne (Jonathan Haze, from Not of this Earth and The Terror)— the latter of whom may not be holding onto his job much longer. Mushnik is just about to fire Seymour when Audrey pipes up that the boy has recently developed some odd new strain of plant that she thinks might be of value to the shop. The boss doubts that anything Seymour would come up with could be in any way worthwhile, but he is convinced to give the stock boy and his gardening project a chance when another regular customer— Burson Fouch (Dick Miller, of The Premature Burial and The Howling), who buys carnations in order to eat them— suggests that florists’ shops that carry unusual plants do better than those that limit themselves to the usual range of merchandise. (Incidentally, I used to date a girl who ate carnations back when I was in high school. If you think it sounds freaky in a movie, wait ‘til you see it happen in person!) After pondering the issue for a moment, Gravis agrees to give Seymour a week— if his new plant improves business, he and it stay. Otherwise, he and the plant are both fired.

Seymour’s plant is a strange goddamned thing. Mostly it’s just a small, leafy mass growing out of a coffee can, but at its center is a large, bud-like organ that opens into something vaguely suggesting the “mouth” of a Venus fly-trap every day at sunset. And it does attract attention. In fact, it proves the decisive influence in convincing a pair of girls from the Homecoming Parade Committee at the local high school (Tammy Windsor and Toby Michaels) to spend their club’s $2000 flower budget at Mushnik’s. The problem is that the plant is sick, and Seymour can’t for the life of him figure out what its unmet biological need is. But with an upturn in the shop’s fortunes clearly riding on this one strange plant, Mushnik makes sure Seymour realizes that his job depends on his ability to discover what the thing wants, and fast. Thus it is that Seymour sticks around after closing time one fateful evening to do some intensive research on his plant. While moving it to what he thinks will be a more favorable position for photosynthesis, he accidentally cuts his finger on the coffee can that serves as its pot, and a few drops of his blood splatter on the inside of the plant’s central bud. The enthusiasm with which the bud snaps shut points inescapably to one conclusion: the missing element in Seymour’s program for the care and feeding of his plant is human blood!

As if to underscore the point, the plant has grown to nearly double its original size by the time Mushnik opens up the store the next morning. Meanwhile, word has gotten out about the strange and fascinating thing growing in a coffee can at Mushnik’s Flowers, and huge crowds are starting to gather. Seymour has become a minor local celebrity, Gravis is running around insisting that the boy call him “Dad,” and Audrey seems to be falling in love with him. In short, everything is going great— that is, apart from one little caveat: the plant (which Seymour has named “Audrey Jr.”) isn’t done growing yet, and it’s hungry again at the next sunset. Oh, yeah— and it can talk now. Seymour is the last one to leave at the end of the day, and as he is locking the front door, he hears Audrey Jr. cry out, “Feed me!” Understandably enough, Seymour isn’t exactly eager to slice open his fingers again, but the plant insists. Finally, Seymour agrees to go out and try to find a solution to his and the plant’s mutual problem. That solution comes in the form of a policeman working undercover at the rail yard, disguised as a hobo. Seymour accidentally beans him on the head when he picks up and throws a big-ass rock out of frustration at his lot, and the undercover cop falls onto one of the tracks just in time to get run over by a passing train. Horrified at what he has accidentally caused to happen, Seymour stuffs what’s left of the body into a sack he finds in a nearby garbage can, and goes looking for a place to dump it. Eventually, he gets an idea. Audrey Jr. wants food, right? The plant eats human blood, right? Seymour has to get rid of the mangled corpse in the sack somehow, doesn’t he? So why not kill two birds with one stone and feed the dead man to the ravenous shrub?

The only problem with this plan is that Gravis Mushnik ends up coming by the shop right when his stock boy is busy stuffing recognizable human body parts into the plant’s maw. Mushnik had been out having dinner with Audrey, and immediately after placing his order, he realized that he had left all of his money in the pockets of another suit. There was still some money in the cash register, though, so Gravis went back to the shop to get it, and so it is that he inadvertently discovers Seymour’s sinister gardening secret. Mushnik’s determination to go to the police is stymied the next morning, though, when he sees the crowd lining up at his door; Gravis has been a poor man all his life, and if the now-car-sized Audrey Jr. can change that, then maybe he can turn a blind eye to one little murder. The same won’t be true, however, of the two detectives who start poking around Skid Row in the wake of their colleague’s disappearance. Sergeant Joe Fink (Wally Campo, of Beast from Haunted Cave and Master of the World) and his partner, Frank Stoolie (A Bucket of Blood’s Jack Warford), may not have any evidence directly linking Mushnik’s shop to the crime, but their visit on the afternoon following it certainly worries both Gravis and Seymour.

We can all see where this is going, right? Audrey Jr. isn’t going to be content with just one dismembered body. It’s growing fast now, and it’s going to need to eat more and more— especially once flower buds start showing up on its stems. And with each hooker and robber and sadistic dentist (the scene with the dentist isn’t really Jack Nicholson’s first film appearance, but it is his second) who finds his or her way into the plant’s hungry mouth, the two cops are going to find more and more clues pointing toward the flower shop. Furthermore, the very success of the shop will eventually turn troublesome, as ever greater numbers of people will be around to notice signs that something isn’t quite right about the place. Seymour and Audrey had better move fast— it doesn’t look like there’s too much time for romance in their immediate future.

You’re never going to believe this, but the first time I saw The Little Shop of Horrors (I was about five years old at the time), it scared the living shit out of me. I seriously didn’t go within arm’s reach of any of my mother’s houseplants for months, and to this day, there are certain species of plant that give me the willies (sunflowers— ugh...). Such an extreme reaction seems all the more puzzling in retrospect because this movie is quite transparently designed as a comedy which just happens to feature a man-eating plant. Most people who watch it today will probably end up evaluating it in terms of the 1986 remake, and the first thing those people are going to notice is how crappy the full-scale model plant in this version looks as compared to the remake’s animatronic Audrey II. They’ll be right, too, as far as that goes, but considering that Steve Martin’s hairdresser probably took home more money at the end of the shoot than Roger Corman spent on this entire production, it’s scarcely a fair complaint to level. If you’re going to bitch about this Little Shop of Horrors, complain about something real, like the fact that the humor in this movie is, if anything, even less subtle than in the ‘86 version. Honestly, though, I think that’s the main reason I like this movie so much. Corman himself admits that both this film and the earlier A Bucket of Blood feel like they were made on a bet, and for my purposes, it’s the “we made this shit up as we went along, and never took a single moment of it seriously” quality that gives The Little Shop of Horrors most of its charm. Charles Griffith’s script displays the same mad sense of humor that would turn up in his Death Race 2000 screenplay fifteen years later, and the most enduring impression The Little Shop of Horrors leaves is that everyone involved in making it was having a tremendous amount of fun. A couple of the gags may fall flat (not enough is made of the “Dragnet” parody angle involving the two detectives, for example), but there is an off-the-cuff immediacy to the proceedings that the more famous remake lacks completely. And whatever else you may think about it, you’ve got to admit that The Little Shop of Horrors is far and away the best horror comedy anybody ever made on a two-day shooting schedule.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact