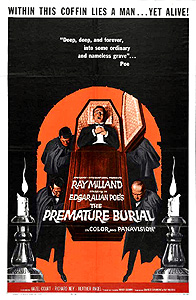

The Premature Burial (1962) **

The Premature Burial (1962) **

The third Poe movie Roger Corman directed for American International Pictures wasn’t supposed to have been an AIP flick at all. The way Corman himself tells the story (in his memoir, How I Made 100 Movies in Hollywood and Never Lost a Dime), it all started with a coin toss— or rather, with three successive coin tosses. Apparently, Corman and AIP honcho James H. Nicholson had an informal arrangement according to which disputes between the two of them over relatively small amounts of money were settled by flipping a coin, and evidently this system had, at the time one such dispute arose over who was getting paid what for The Pit and the Pendulum, decided in Nicholson’s favor on the previous two consecutive occasions. Corman seems to have expected Nicholson to reckon that fairness required him to forego their custom in this case, on the grounds that the latter man had already come out ahead twice in a row. But instead, Nicholson pulled out a coin, and Corman lost the toss again. It wasn’t enough to sour the long and productive working relationship the two men had developed, but Corman was still miffed enough that he decided to make a movie without Nicholson’s involvement. The film was to be another Poe adaptation, this time derived (insofar as any of these movies could honestly be described as deriving from their supposed source material) from the comparatively obscure “The Premature Burial.” Without AIP to back him, Corman wouldn’t be able to pay for Vincent Price, so instead, he hired Ray Milland for the central role. But then a funny thing happened on the first day of shooting. Nicholson showed up on the site with his partner, Samuel Z. Arkoff, as if they wanted to sit in on the filming. Neither producer ever did this, even on movies that were being made for their studio, so Corman immediately knew something was up. Well, it turns out the old weasels had gone behind Corman’s back, and bought the rights to The Premature Burial from its original backers! Corman laughs the incident off in his memoir, but I’ll bet he was pretty pissed at the time.

I tell you this story because it’s frankly a hell of a lot more interesting and entertaining than anything that goes on in the movie itself. The Premature Burial is, by a fair margin, the worst of Corman’s Poe films, edging out even the soulless, overproduced Masque of the Red Death. (Of course, both of these movies are at least watchable; the real stink-bombs wouldn’t start going off until AIP began getting its Poe flicks from other directors.) Despite having a different star and a different screenwriter, it offers nothing that we haven’t already seen in either The Fall of the House of Usher or The Pit and the Pendulum. In almost total disregard for the original story, it’s just another predictable tale of catalepsy, madness, dark secrets, and hereditary misfortune.

Okay, so there is one difference. This time around, the person who comes from far away to visit an incommunicado lover is a woman. Her name is Emily Gault (Hazel Court, from Dr. Blood’s Coffin and The Masque of the Red Death), and she arrives on the doorstep of the isolated and sepulchral Carrel Manor looking for her fiance, Guy (Milland, whom we’ve also seen in X! and The Thing with Two Heads). Guy’s sister, Kate (The Undying Monster’s Heather Angel), tries to stop Emily from coming in, saying that Guy has told her not to let his betrothed— with whom he has decided to terminate his engagement— into the house. Emily won’t have it, though, understandably insisting on hearing the words from Guy’s own mouth; she pushes her way past Kate, and barges into Guy’s suite.

So why do you suppose Guy wants to break it off with Emily? Yeah, it’s another one of those “family curse” deals (sigh...). And it’s not even a good family curse, for fuck’s sake! No “evil and insanity run in my lineage,” no “my dad was the most brutal torturer in the history of the Spanish Inquisition,” not even “all the men in my family like to dress in women’s clothing.” No, Guy’s “curse,” for the sake of which he intends to turn his back on a promising relationship with a woman he loves and who loves him in return, is nothing but a suspected— suspected!— family history of goddamned catalepsy. Suck it up, man! If I’m up to the challenge of spending my life with a suicidal paranoiac, surely Emily can handle a little thing like catalepsy! And more incredible still, Guy has no real reason to believe he’s cataleptic in the first place. He’s never had a seizure— not even a mild one— and his sister is completely free from any such affliction. Indeed, the entire evidentiary foundation for his self-diagnosis is the fact that he thinks he heard his father cry out in his tomb shortly after his interment. Of course, no one else in his household heard anything of the kind, and Guy himself was very young at the time. You might think this would give him pause and lead him to consider the possibility that he simply imagined the whole ghastly incident, but since this is a movie at least loosely grounded in Poe’s writing, we’ll have none of that “common sense” crap around here!

The rest of the story is easy enough to condense, because there really isn’t much of it to begin with. Guy and Emily are married, but Guy’s obsession worsens at an ever-accelerating rate, and he soon starts devoting every waking moment to the design and construction of the tomb of his dreams. The idea underlying the mausoleum’s every feature is that it should be impossible for a person who wants out to become trapped inside it. There are three different ways out of the coffin, four different ways out of the crypt itself, devices for summoning rescuers, provisions for a week’s worth of food and water, and if all of that should fail, there’s even a sealed goblet of poison in an alcove in the wall on the theory that it is better to die that way than by starvation, suffocation, or thirst. Needless to say, Guy’s insanely intricate preparations for his own premature burial give Emily a serious case of the creeps, and she calls in her old friend, Dr. Miles Archer (Richard Ney), to have a look at her husband. Archer eventually decides that the only thing for it is to force Guy to choose between his unhealthy obsession and something else of equal importance to him— Emily, for instance. It isn’t an easy decision for Guy to make, but in the end, he consents to having the tomb blown up, forcing himself to get on with his life.

Real obsession does not die so easily, however, and no matter how skillfully he might conceal it from Archer, Emily, and his physician father-in-law (Alan Napier, from The Mole People and Island of Lost Women), Guy’s morbid turn of mind never really goes away. He continues to worry constantly about being buried alive, and even goes on having hallucinations involving the two grave robbers who work for Dr. Gault (John Dierkes, from The Haunted Palace and Daughter of Dr. Jekyll, and Dick Miller, king of the bit-parts, whom we’ve encountered before in Truck Turner and Rock ‘n’ Roll High School). Sooner or later, Guy’s secret has to come out, and when it does, Archer convinces him that the only way he’ll ever be free of his obsession is to go down to the vault in the cellar, and open his father’s tomb. Then he’ll see that his father has rested peacefully, well and truly dead long before he was sealed up in the wall of the tomb. (And yeah, I do believe that is the same vault set from the corresponding scene in The Pit and the Pendulum.) We all know what to expect by now. When his tomb is opened, Dad’s body proves to have been leaning against the outer wall; it falls out and lands right on Guy, who has a heart attack and dies on the spot. But it wouldn’t be The Premature Burial if Guy were really dead, would it? Certainly not. His apparent death really is just a cataleptic trance, and Guy now finds his worst nightmare coming true. And whoops!— he went and blew up his special crypt, didn’t he? The only thing that saves Guy from the horrible fate he’s feared since he was a boy is those same two grave robbers, who dig him up to sell him to Emily’s father, and who become the first victims of Guy’s insane revenge. Or is it so insane after all? Guy himself may not realize it, but we in the audience have begun seeing evidence that somebody close to Guy may have wanted him dead all along...

There is the nucleus of a good movie in The Premature Burial. Unfortunately, most of that nucleus is recycled from The Fall of the House of Usher and The Pit and the Pendulum, and three consecutive movies spent tinkering with the same material is at least one too many. Indeed, the only feature this film has with which to establish its own voice is Guy’s delightfully paranoid design for his tomb, and it isn’t in the movie for very long. Everything else— the catalepsy, the “revenge of the resurrected,” the grave robbers, the crooked doctor, the setting, the basic story structure— is lifted either from one of the previous AIP Poe movies or from one of the zillions of Burke and Hare flicks that were released over the preceding 30 years. Casting is another problem— Ray Milland is no substitute for Vincent Price. Price alone wouldn’t have rescued The Premature Burial from mediocrity, but his presence would certainly have been an improvement. In addition, Richard Ney is completely uninteresting as the other male lead, and Hazel Court is wasted in the hopelessly underwritten role of Emily. With all this working against it, it makes perfect sense that The Premature Burial would fare far worse at the box office than either The Fall of the House of Usher or The Pit and the Pendulum. But some good did ultimately come of it; the disappointing returns on The Premature Burial convinced Corman and his partners that the formula for the first round of Poe movies was all played out, and subsequent entries in that loosely constituted series would all display more markedly individual personalities.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact